The Jewess Hana and Anti-Semitism in the Soviet Bloc

Tomasz Kamusella

University of St Andrews

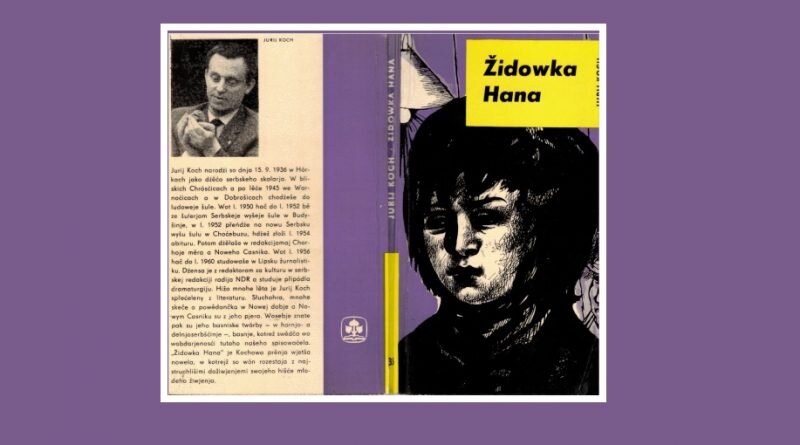

Jurij Koch. 1963. Židowka Hana [The Jewess Hana] (Ser: Kapsne knihi LND, Vol 35). Budyšin [Bautzen, East Germany]: Ludowe nakładnistwo Domowina. 114pp, illustrated by K. G. Müller.

Cover of Židowka Hana (1963)

Cover of Židowka Hana (1963)

(Source: my own scan)

While reading idly books published in too little known languages one is sure to stumble across a treasure. After the academic year of 2019/2020 – blighted by the ongoing pandemic – finally came to an end, I spoiled myself with a shipment of nifty volumes in eastern Germany’s Slavic language of Sorbian. Nowadays, after the Germanizing ravages in nazi Germany (1933-1945) and the subsequent subjection of Sorbian language and culture to communist East Germany’s ideological needs,[1] not more than 40,000 to 50,000 people have a command of this language. All Sorbian-speakers are bilingual in German, yet fewer than half of them use Sorbian in everyday life.[2] Following the eastward enlargement of the European Union in 2004, quite usefully, their language allows Sorbs to understand Czech, Polish and Slovak quite easily. A good addition to one’s CV, when one is searching for a job in polyglot Europe.

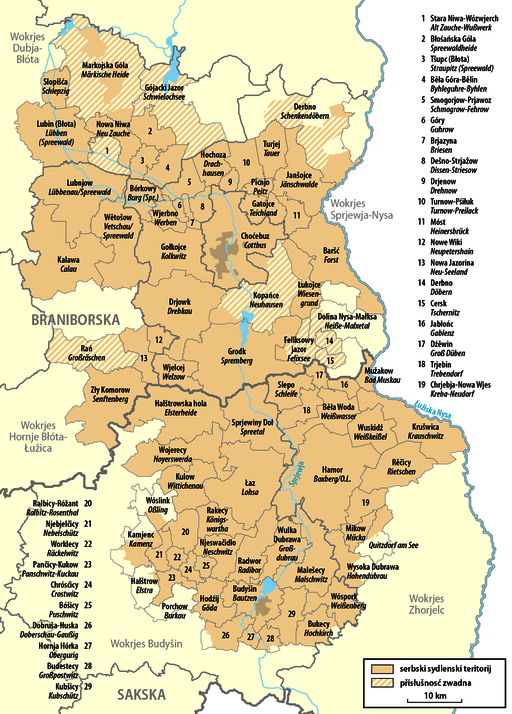

(Source: NordNordWest / CC BY-SA 3.0, Wiki-Media Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sorbisches_Siedlungsgebiet-hsb.png)

(Source: A. Gutwein / CC BY-SA, Wiki-Media Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:F60_in_Betrieb.jpg)

Lignite, or brown call, was quarried in the Sorbian historical region of Lusatia (nowadays split between Brandenburg and Saxony) for centuries, but since the 1860s mining commenced on an industrial scale. Open-cast mines were introduced during the communist period,[3] necessitating the levelling of over 130 Sorbian villages and still counting.[4] The inhabitants were relocated and dispersed in the nearby German-speaking towns and cities. In this manner the overwhelmingly Sorbian-speaking rural communities disappeared overnight, and their former members had no choice but to shift to German for everyday communication. What discriminatory could not achieve in the Third Reich was ensured by ‘progress, industrialization and socialism’ in East Germany. Strangely, following the fall of communism and the reunification of Germany, not much changed. The ‘economic need’ of securing lignite for the power plants that keep producing extremely ‘dirty’ energy translates into the destruction of further Sorbian villages.[5] The environmental disaster is intimately intertwined with the cultural catastrophe. Despite subsidies for Sorbian schools and cultural organizations, Berlin seems rather unperturbed by the looming disappearance of the last Sorbian-speaking communities.[6]

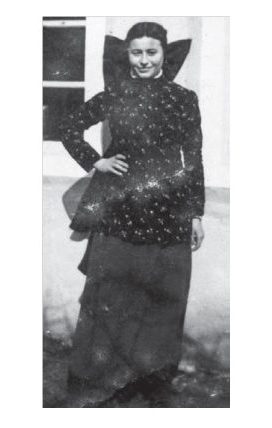

(Source: www.posol.de/fck/file/Sercec__KP__2014.pdf; NB: public domain)

The aforementioned parcel of books arrived from Budyšyn, or Bautzen in German. Until 1868 the German spelling of this town’s name was Budissin, in essence a Latinate rendering of the originally Sorbian name. Among the beautifully crafted volumes, an old 1963 pocket book caught my eye, namely, Židowka Hana, or The Jewess Hana. It relates the poignant story of Hanka Šěrcec (also spelled in German as Schierz; originally, Annemarie Kreidl, 1918-1943). Her biological mother, Gertrude, was born to the well-to-do owners of an apparel shop in the Saxony’s capital of Dresden, namely, Bertha[7] and Carl Kreidl.[8] At the turn of the 20th century, this German-speaking family of a Jewish background had moved to the Kingdom of Saxony in the German Empire from the nearby Crownland of Bohemia (at present, western Czechia) in Austria-Hungary. When she was a 17-year-old teenager, unmarried Gertrude got pregnant. In this high age of patriarchalism, a child of wedlock was a huge social problem for any respectable bourgeois family. In order to prevent a scandal, she left Dresden for the village of Horka (Hórki in Sorbian), near Crostwitz (Chrósćicy), located about 50 kilometers northeast of her home city.[9] In Horka Gertrude befriended Marja (Maria) and Jurij (Georg) Šěrcec (Schierz), sister and brother. They hosted Gertrude in their house and took care of her. In 1918, at the height of historic and social upheavals sweeping across Europe in the wake of the Great War, Gertrude gave birth to Annemarie, and soon afterward entrusted the baby to these peasant sister and brother.

(Source: www.posol.de/fck/file/Sercec__KP__2014.pdf; NB: public domain)

Marja and Jurij brought up Annemarie as their own daughter, speaking Sorbian, and in the Catholic faith. In 1925 they formally adopted her, so Annemarie’s family name was officially changed to Schierz. Her stepparents and the neighbors called the girl Hanka. Meanwhile, in Dresden, Gertrude married a befitting spouse, who happened to be a factory owner. After finishing her elementary school in 1933, Hanka began to work as a household servant, and also in the fields. At that time when many young women preferred modern-style ‘city’ clothing, Hanka made the point to always wear the traditional Sorbian folk costume. Yet, she knew about her biological mother, and under this influence chose the Jewish name ‘Esther’ for her Catholic confirmation in 1934.[10] In the wake of the racist Nuremberg Laws of 1935, people with a parent or grandparent of the Jewish religion were required to sign a Nichtariererklärung (declaration of non-Aryan origin). Hanka signed the document in 1937, but shirked the yellow star, which Germany’s Jews were required to wear beginning in 1939. Hanka’s stepfather Jurij had joined the NSDAP already in 1933, hoping to protect his stepdaughter. But Gestapo had Hanka already in their crosshairs.[11]

This is the moment when the novel’s plot commences. The doyen of Sorbian literature, Jurij Koch, happened to know the story of Hanka, because he was born in 1936 in the same village of Horka to a stonecutter’s family. Židowka Hana was his first novel that properly launched Koch’s career as a full-fledged Sorbian man of letters. A decade later, in the early 1970s, Koch also began writing in German and self-translating his Sorbian books into this language. At present, aged 84, he is the most prolific Sorbian writer alive. Sadly for Sorbian culture and language, there are no obvious successors in sight.

The novel opens and closes with the haunting image of an oppressive prison. At the book’s beginning it is a psychiatric hospital, where mentally unwell people are apparently killed in line with nazism’s eugenic principle of ‘life not worth living.’ However, in the coda this palace is clearly a concentration camp with Hana in it, wasting away, waiting for the inevitable, or the genocidal ideology’s ‘final solution.’ Within these haunting brackets, life is still as what it used to be in the countryside, governed by the natural cycle of seasons, Catholic holidays and fieldwork. The plot meanders between the village’s quarry, tavern and Hana’s house. In 1939 a serious and courteous young stonecutter, Bosćij (Sebastian) Lubak, decorously woos Hana in these inauspicious times. Policeman Beier always speaks German and does not seem to understand any of this ‘damned Sorbian gibberish.’ In the tavern he drinks and plays cards with stonecutters, making sure they speak German. He also keep an eye on communists in this unruly bunch of Slavic fellows, who duplicitously pass themselves as Germans. It seem that Beier killed the hard-of-hearing stonecutter Krawc, who kept talking in Sorbian, having not noticed that the policeman happened to be nearby.

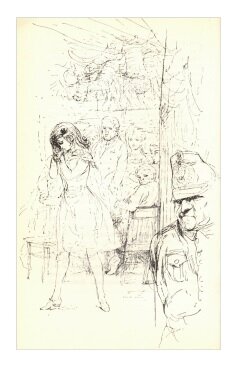

Židowka Hana (1963), p 48 (Source: my own scan)

In 1941 a persistent rumor starts to spread that Hana is a Jewess. On St Nicholas’s Day (6 December), as usual, she dresses up as this saint, who traditionally brings presents to Catholic children across central Europe. Beier also asks Hana to hand the presents to his children. Although reluctant at first, the girl convinces herself that it is only a Christian thing to do, and that she should not blame people without a proof. Three weeks later, Bosćij invites her to the dances on the New Year’s Eve. Hana would prefer to stay home, but agrees. Shockingly, Beier orders her to leave the hall in front of all the villagers to humiliate Hana the more. Sometime later, the priest asks Hana not to come to church for holy mass. He alludes that it was Beier’s strong suggestion, which he has no choice but to follow.

Isolated and excluded from her village community, the loyal Bosćij remains Hana’s only hope. In mid-1942 an unexpected letter arrives from Switzerland where Gertrude (Hana’s biological mother) and her husband managed to flee from the increasingly anti-Semitic Third Reich. Bosćij and his stonecutter friends with links to a leftist resistance group take the decision to transport Hana to safety in Switzerland, where she could join her parents. Meanwhile, in early August, Beier orders Hana to come to the tavern, where in front of all the village it would be finally ascertained whether she is a Jewess or not. Hana fails to appear at the scheduled ‘trial.’ Bosćij, together with a couple of stonecutters whisk Hana away in a truck.

Beier easily sees through the charade and alarms Gestapo. The truck is swiftly discovered and stopped in no time. As a result, Hana is sent to a concentration camp, while her sweetheart and his friends are ordered to the eastern front. Bosćij survives the war, which now with the advancing Read Army troops has arrived in the Sorbian homeland, then located in the midst of Germany. But no one knows what has happened of Hana.

In real life, Hana had to stop wearing the folk costume so that not to be accused of concealing her Jewishness under the Sorbian façade. In August 1941, her 70-year-old stepfather Jurij died after another brutal Gestapo interrogation. Beginning in this year, Hana had to regularly report to Gestapo in Dresden. In documentation there is no trace of Hana after August 1942. Perhaps, she was sighted in the Litzmannstadt (Łódź) Ghetto in occupied Poland. If that is true, Hana either died there in 1943, or in an extermination camp. Jews from this ghetto were typically sent to the Kulmhof (Chełmno) or Auschwitz (Oświęcim) death camp. A year earlier, in 1942, her Jewish grandmother, Bertha, aged 69, perished in the Theresienstadt (Terezín) Ghetto in occupied Czechoslovakia.[12] Hana’s stepmother Marja, with all her immediate family dead, and persecuted as a harborer of ‘this Jewess Hana,’ died in 1948, aged 75. We know nothing about the fate of Hana’s biological mother, Gertrude, and her husband.

There are as many stories like that, as the six million Jews murdered by Germans, Austrians and other nazi supporters across Europe. The surprise is that communist East Germany’s censors permitted the publication of a wartime novel with the ethnonym Jew/ess prominently featuring in its title. In support of the fraternal alliance with the Soviet Union, East Germany’s ruling Communist Party (SED, Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands) encouraged the writing and publication of ‘anti-fascist literature.’[13] The goal was to prove this country’s impeccable ‘socialist and internationalist’ credentials, in stark contrast to the ‘rotten capitalist West Germany’ that cherished such convicted nazi criminals against humanity, as industrialist Alfried Krupp.[14]

Undoubtedly, Koch’s novel fulfills the party’s appeal for anti-fascist literature. Yet, this book, without stating that openly, unequivocally alludes to the Holocaust, too. Everyone who lived through the war immediately knew what the writer was talking about. But this was a taboo topic then in the increasingly anti-Semitic Soviet bloc, including East Germany that obediently toed the Kremlin’s line.[15] The official line was that all the inhabitants suffered equally during the war, irrespective of creed or language. The Soviet Jewish writers, Ilya Ehrenburg and Vasily Grossman’s, The Black Book of Soviet Jewry was suppressed already in 1948. Joseph Stalin’s domestic reaction to the beginning Cold War took the form of a campaign against the ‘rootless cosmopolitans,’ which was a code-phrase for Jews. This purge culminated in the destruction of Yiddish language and culture,[16] alongside the extermination of leading Soviet Jewish intellectuals and writers from 1950 to Stalin’s death in 1953.[17] For instance, the first volume of the most famous Yiddish-language Soviet author, Der Nister’s, trilogy The Family Mashber was published in 1939 in Moscow. The second volume came off the press in 1948 in New York, while the third has been lost until now in the KGB’s archives.[18] The KGB arrested the writer in 1949, and the following year he died in Vorkuta.[19]

The Soviet bloc’s countries followed suit, for example, staging show trials of high-ranking communist functionaries, some of Jewish origin, in Hungary,[20] Czechoslovakia,[21] or Romania.[22] The subsequent flights and expulsions of Jews from these countries were ‘rounded up’ with communist Poland’s 1968 ethnic cleansing of Jews.[23] Until the end of communism, history textbooks and museum concentration camps in the Soviet bloc took care to not reflect on the ethnicity or religion of the Holocaust or war victims. For instance, Jews constituted the overwhelming majority of the over one million people murdered in Auschwitz.[24] Yet, during the communist period all the victims were simplistically referred to as ‘Poles.’[25]

Obviously, books and films about war heroes, and on brave resistance fighters’ struggle against bloodthirsty hitlerites were a commonplace across the Soviet bloc. Yet, not only using the ethnonym ‘Jew’ in the title was out of bounds. Communist censorship made sure that no discernible Jew could feature as a main protagonist, even if he was a staunch communist, patriot and atheist. Vasily Grossman learned this lesson the hard way, when in 1960 the KGB ‘arrested’ his war opus magnum Life and Fate, oft-compared with Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace. Eventually, a quarter of a century after the writer’s death, Mikhail Gorbachev freed the novel, and allowed for its publication in 1988, that is, a year before the fall of communism, and three years prior to the breakup of the Soviet Union.[26]

This historical context makes the publication of Židowka Hana doubly unusual. The Sorbian-language novel appeared in 1963, or at the bitter end of the Khrushchev Thaw.[27] A year later the Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, lost power to a more hardline and less mercurial coterie led by Leonid Brezhnev. In 1966 a Lower Sorbian translation of Koch’s novel appeared, titled, Žydowka Ana,[28] or just a year prior to the rift between Israel and the Soviet bloc in the wake of the 1967 Six Days’ War. Somehow, the subsequent anti-Israeli rhetoric[29] did not prevent the second edition of the Upper Sorbian original brought out in 1972. Maybe the beginning of the détente between east and West helped.[30] But in the end, East Germany’s censors appear to have woken up to a novel with an ideologically unpalatable title, especially because it was relatively popular among the country’s ‘untrustworthy’ Sorbian-speakers. Tellingly, afterward the book was never republished, or let alone translated into German during the communist years.

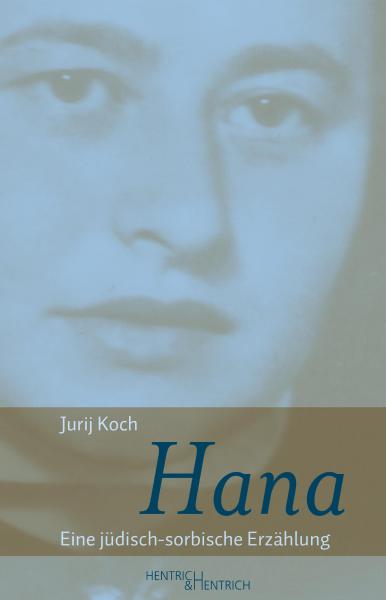

(Source: Publisher’s website, https://www.hentrichhentrich.de/buch-hana.html)

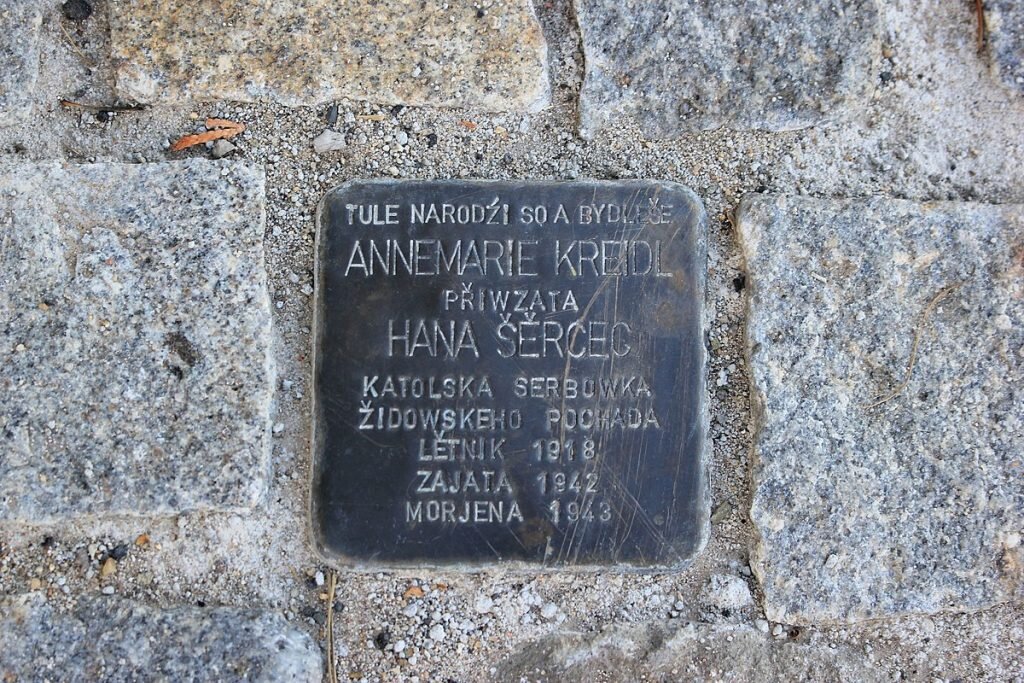

The end of communism and the reunification of Germany took precedence over such stories. During the 1990s and at the beginning of the 21st century, former East Germans were busy finding their own place in the reunified Germany, where they felt to be second-class citizens. No excess empathy was left to be expanded to the country’s ethnically non-German Sorbs or Jews. Apparently, it was Ft Clemens Rehoronly of Crostwitz/Chrósćicy Parish, who inspired some secondary school students to make the story of Hana into their school project at the turn of the 2010. This led to more research and, in 2014, to the installation of the first-ever Stolperstein (commemoration ‘stumbling stone’ for a Holocaust victim) written in Sorbian.[31] Fittingly, this stone is devoted to Hana.[32] Last but not least, the unprecedented developments must have, at long last, convinced the 84-year-old writer to seize this opportunity. He self-translated the novel into German, and titled it Hana. Eine jüdisch-sorbische Erzählung (Hana: A Jewish-Sorbian Story). Leipzig’s publishing house specializing in Jewish culture and history, Hentrich und Hentrich, will officially release this long overdue translation in July 2020,[33] that is, on Hana’s 102nd birthday, 77 years after her death, and 57 years after the book’s original publication.

(Source: Julian Nyča / CC BY-SA, Wiki-Media Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hórki_–_kopolak_za_Hanu_Šěrcec.jpg)

Maybe, on this memorable occasion, a journalist or a scholar will convince the old great man of Sorbian literature to reveal how he dealt with the censors. How Jurij Koch and the Sorbian-language publishing house Domowina managed to convince the East German apparatchiks tasked with controlling the Sorbs and their culture that it would be a good idea to permit an explicitly Jewish-themed novel to be published in communist East Germany. For that matter not once, but as many as three times, in spite of the official anti-Semitic line, adopted in the Soviet bloc since the turn of the 1950s. The line, which after 1967, was deepened by Moscow’s explicit anti-Zionism.

I suspect that the rather small number of potential readers, fully contained to the Sorbian-speaking community, could be an explanation. Although, as a matter of course, quite a few Sorbian books were translated into German and also into Czech, Polish or Russian during the communist period for the sake of fostering ‘international socialist culture,’ Židowka Hana did not appear in any of these languages. It just lingered in its Upper Sorbian original, and the Lower Sorbian translation, inaccessible to non-Sorbian-speaking East Germans. On the other hand, this novel might be also a tacit warning to ‘anti-socialist elements,’ guilty of crimes against humanity committed in the Third Reich, that the ruling SED and Moscow knew and remembered. So they had better closely observe the party’s guidance, or else.

(Source: Claude Lebus / CC BY-SA 3.0, Wiki-Media Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jurij_Koch_(1995).jpg)

The intertwined story of Hana and Jurij Koch’s novel devoted this Catholic Sorbian Jewess has been long and unusual, with no end in sight yet. The sad fate of Hana should be better and more widely known. More research needs to be done. Yes, lest we forget. Hence, I hope an English translation of this novel’s Sorbian original will follow swiftly, and that the book will be also published in Czech, Polish and other central European languages. Each and every day, speakers of these languages and of the German language, too, tread on the ruins and bones of Yiddishland, or the world of central Europe’s Jews, who are no more.

June 2020

[1] Nuk, Michał. 2004. Zatajena njeprawda. Politisce přesćěhani w Serbach mjez 1945 a 1989 [The Hidden Truth: Political Repressions Against the Sorbs Between 1945 and 1989]. Budyšin: Ludowe nakładnistwo Domowina.

[2] ferrarij. 2015. Sorbian: An Endangered Language. Taylor Institution Library: A Bodleian Libraries Weblog. 23 Nov. http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/taylorian/2015/11/23/sorbian-an-endangered-language/. Accessed: Jun 19, 2020.

[3] Lippert, Ingmar. 2018 [Pre-Print]. „Earth … without us”: Earthlessness, Autochthoneity and Environmental Risk in Negotiating Mining in Germany.

[4] Brelie, Hans von der. 2015. Germany and Poland have a Dirty Big Secret: An Addiction to Brown Coal. euronews. 30 Dec. https://www.euronews.com/2015/12/30/germany-and-poland-have-a-dirty-big-secret-an-addiction-to-brown-coal. Accessed: Jun 19, 2020.

[5] Lignite Mining in Lusatia: An Environmental and Cultural Catastrophe. 2015. Greens/EFA. 25 Feb. https://www.greens-efa.eu/en/article/news/lignite-mining-in-lusatia-an-environmental-and-cultural-catastrophe/. Accessed: Jun 18, 2020.

[6] Cf Sorbian Language Faces Extinction Due to Lack of Teachers. 2010. Nationalia: World news – Stateless Nations and Peoples and Diversity. 16 Jun. https://www.nationalia.info/new/9207/sorbian-language-faces-extinction-due-to-lack-of-teachers. Accessed: Jun 19, 2020; The Battle in Chroscicy to Maintain the use of Sorbian in Education and Administration for the Sorbian Population which Has Traditionally Lived in Upper Lusatia, Saxony. 2002. European Parliament. 7 Jun. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?type=WQ&reference=E-2001-2519&language=EN. Accessed: Jun 19, 2020.

[7] Berta Dorothea Kreidl (Stransky). 2020. Geni. https://www.geni.com/people/Berta-Kreidl/6000000015216381993. Accessed: Jun 20, 2020.

[8] Carl / Karl Kreidl. 2020. Geni. https://www.geni.com/people/Carl-Karl-Kreidl/6000000083839550858. Accessed: Jun 20, 2020.

[9] Hórka. 2020. Wikipedija. https://hsb.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hórka. Accessed: Jun 18, 2020.

[10] Haase-Hindenberg, Gerhard. »Erzählt es euren Kindern«. 2019. Jüdische Allgemeine. 20 Jun. https://www.juedische-allgemeine.de/unsere-woche/erzaehlt-es-euren-kindern/. Accessed: Jun 20, 2020.

[11] Jěwa-Marja Elic. 2014. Ze žiwjenja storhnjena – nic pak z pomjatka Hanka Šěrcec – katolska Serbowka židowskeho pochada (pp 268-269). Katolski Posoł. 14 Sept. www.posol.de/fck/file/Sercec__KP__2014.pdf. Accessed: Jun 18, 2020; Kirschke, Andreas. 2014. Erinnerungen an eine herzensgute Frau. Sächsische.de. 16 sept. https://www.saechsische.de/plus/erinnerung-an-eine-herzensgute-frau-2929486.html. Accessed: Jun 18, 2020; R. Ledźbor. 2014. „Nětko mam k njej naraz wěsty zwisk“ W Hórkach kopolak-plesternak za katolsku Serbowku židowskeho pochada Hanu Šěrcec połoženy (pp 276-277). Katolski Posoł. 21 Sept www.posol.de/fck/file/Sercec__KP__2014.pdf. Accessed: Jun 18, 2020.

[12] Berta Dorothea Kreidl (Stransky). 2020.

[13] Cf Baumann, Barbara and Oberle, Brigitta. 1996. Deutsche Literatur in Epochen. Ismaning: Max Hueber Verlag, pp 261-262.

[14] Cf Kamusella, Tomasz. 2019. Krupp in Greifswald: On the Perils of Forgetting about the Holocaust. New Eastern Europe. 18 Jun. https://neweasterneurope.eu/2019/06/18/krupp-in-greifswald-or-on-the-perils-of-forgetting-about-the-holocaust/. Accessed: Jun 20, 2020.

[15] Cf Kelly, Elaine. 2014. Composing the Canon in the German Democratic Republic: Narratives of Nineteenth-Century Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p 77.

[16] Night of the Murdered Poets. 2020. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Night_of_the_Murdered_Poets. Accessed: Jun 21, 2020.

[17] Doctors’ Plot. 2020. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doctors%27_plot. Accessed: Jun 21, 2020.

[18] Kestenbaum, Gloria. 2019. Hidden Chapters. The New York Jewish Week. 16 Jul. https://jewishweek.timesofisrael.com/hidden-chapters/. Accessed: Jun 21, 2020.

[19] JTA. 2017. Der Nister Hidden No More: Grave of Influential Yiddish Writer and Soviet Resistance Fighter Discovered at Former Gulag. Jewish Standard. 30 Aug. https://jewishstandard.timesofisrael.com/der-nister-hidden-no-more/. Accessed: Jun 21, 2020.

[20] Cf Hodos, George H. 1987. Show Trials: Stalinist Purges in Eastern Europe, 1948-1954. New York: Praeger.

[21] Slánský Trial. 2020. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slánský_trial. Accessed: Jun 21, 2020.

[22] Pauker, Ana. 2020. The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Pauker_Ana. Accessed: Jun 21, 2020.

[23] Sieradzka, Monika. 2018. Poland Marks 50 Years since 1968 anti-Semitic Purge. DW. 8 Mar. https://www.dw.com/en/poland-marks-50-years-since-1968-anti-semitic-purge/a-42877652. Accessed: Jun 21, 2020.

[24] Narodowość i liczba ofiar Auschwitz. 2020. http://70.auschwitz.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=65&Itemid=176&lang=pl. Accessed: Jun 21, 2020.

[25] Cf Dąbrowa, Sławomir. 1973. Ludność cywilna w konfliktach zbrojnych. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Ministerstwa Obrony Narodowej, p 218.

[26] Life and Fate. 2020. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Life_and_Fate. Accessed: Jun 21, 2020.

[27] Khrushchev Thaw. 2020. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khrushchev_Thaw. Accessed: Jun 21, 2020.

[28] Koch, Jurij. 1966. Žydowka Ana [translated into Lower Sorbian by Wylem Bjero]. Budyšyn (Bautzen): Domowina.

[29] Soviet anti-Zionism. 2020. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soviet_anti-Zionism. Accessed: Jun 21, 2020.

[30] Détente. 2020. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Détente. Accessed: Jun 21, 2020.

[31] Liste der Stolpersteine in Crostwitz. 2020. Wikipedia. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liste_der_Stolpersteine_in_Crostwitz. Accessed: Jun 19, 2020.

[32] Eine Märtyrerin in Horka. 2018. Sächsische.de. 14 Aug. https://www.saechsische.de/plus/eine-maertyrerin-in-horka-3995079.html. Accessed: Jun 19, 2020.

[33] Koch, Jurij. 2020. Hana. Eine jüdisch-sorbische Erzählung. Leipzig: Hentrich und Hentrich. Der Verlag für jüdische Kultur und Zeitgeschichte. ISBN: 978-3-95565-372-9.