Russian and Authoritarianism: The Question of ‘Big Languages’ and Freedom

Russian and Authoritarianism:

The Question of ‘Big Languages’ and Freedom

Tomasz Kamusella

University of St Andrews

‘Big Languages’ and Freedom

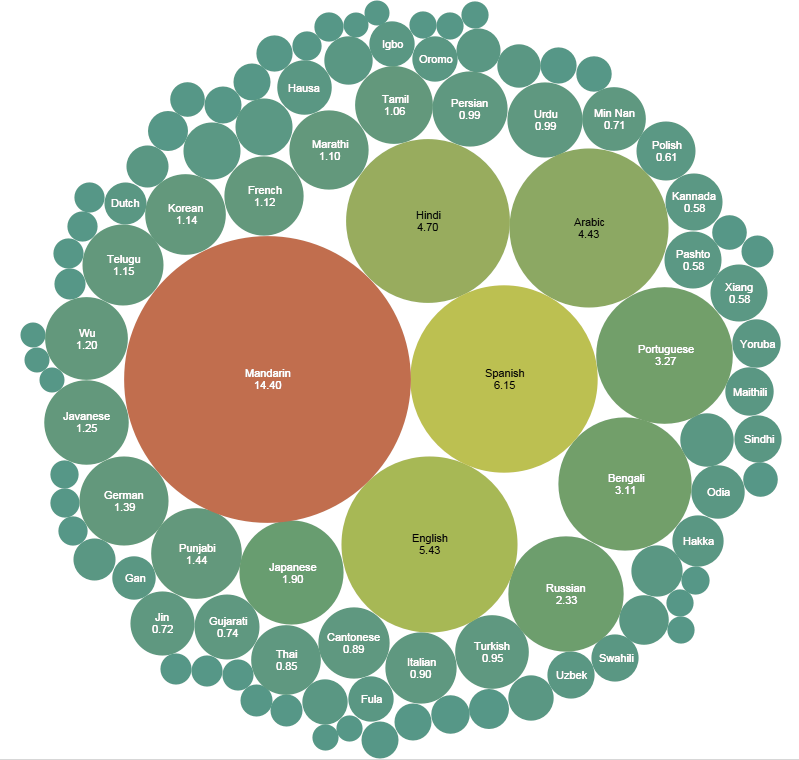

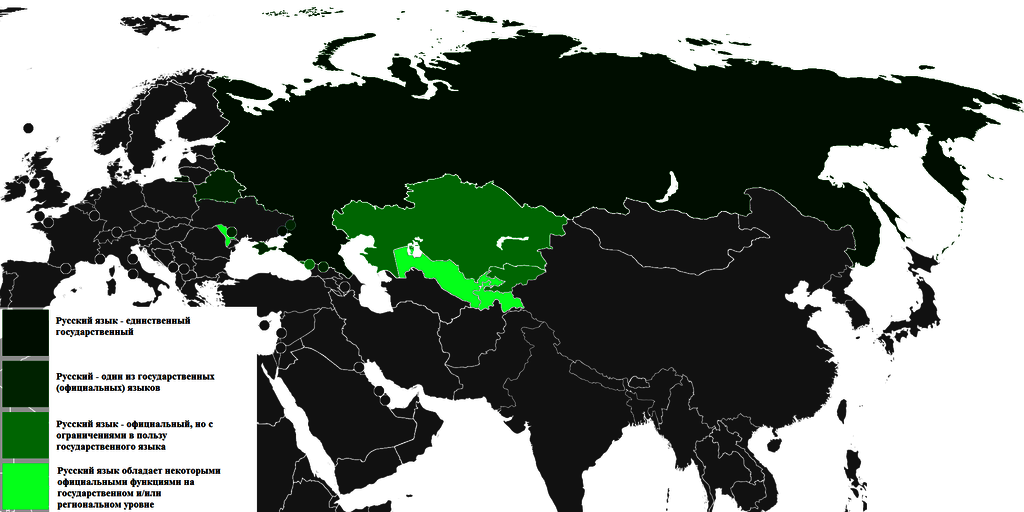

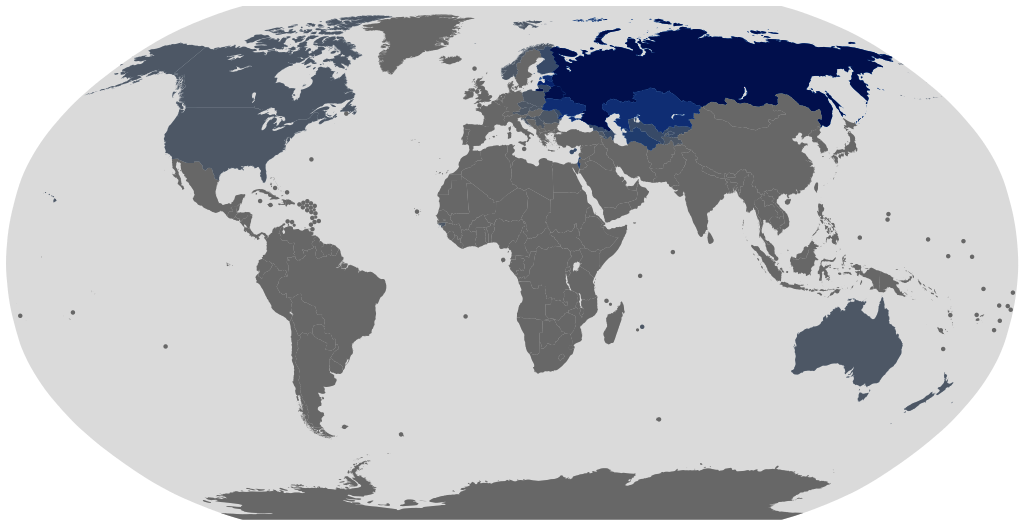

Russian is one of the so-called ‘big’ or ‘world’ languages. This term denotes languages that are official in multiple countries across the globe, for instance, Arabic, English, French, Spanish, or Portuguese. All these languages and their widespread (transcontinental) use are a legacy of one empire or another that broke up in a recent or more distant past. Russian is no different in this respect. The language’s empire of origin is none other than the Russian Empire that in the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution morphed into an equally imperial in its character Soviet Union. This communist empire of the Soviet Union split in 1991, producing 15 successor nation-states. Some of these independent countries adopted Russian as an official or co-official language.

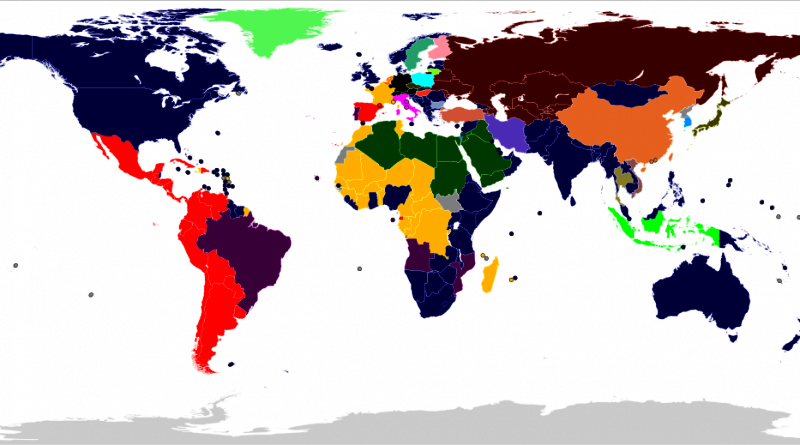

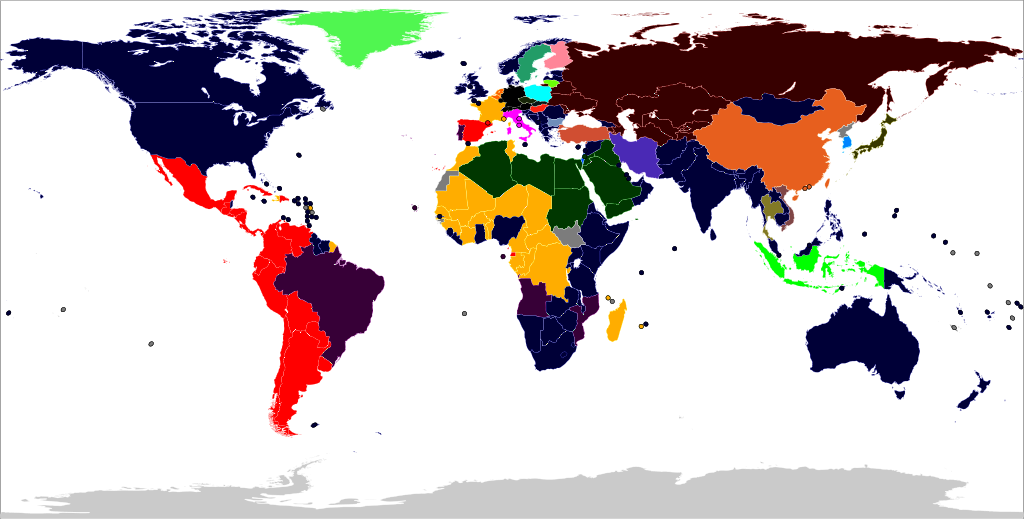

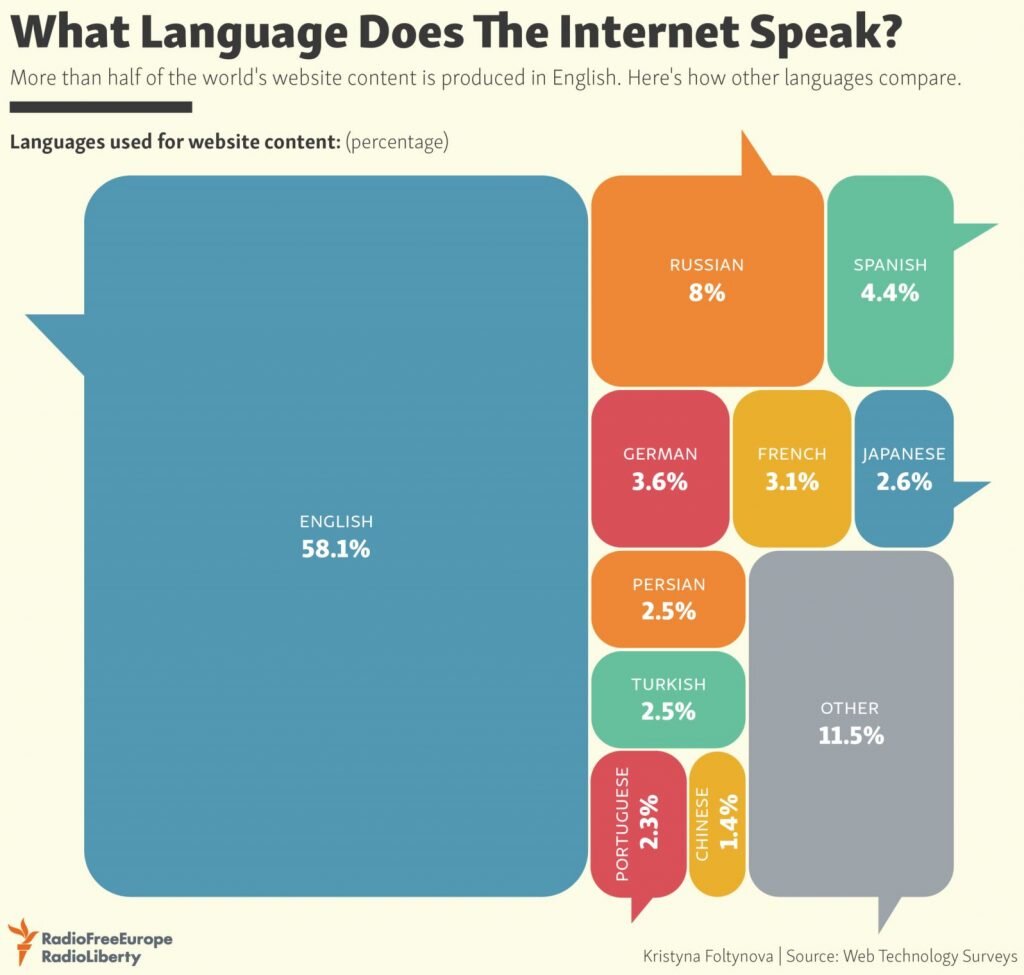

in official and de facto use, and as preferred languages of online information assess

(Dark Green – Arabic, Navy Blue – English, Yellow – French, Black – German, Brown – Russian, Red – Spanish, Purple – Portuguese)

(Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Most_popular_language_version_of_Wikipedia_by_country_2013_Q4_ALL.svg)

Interestingly, none of the post-Soviet polities with Russian as an official language is a democracy. Russian as a ‘big language’ shares this notorious badge of distinction only with Arabic. According to the current (2020) Freedom House ranking of political rights and civil liberties,[1] all Arabicphone states are not free, with the recent exception of Tunisia. It is the sole state, where the promise of the Arab Spring (2011) was tentatively fulfilled, at least for now. Otherwise, Arabic-speaking polities just differ in the degree of unfreedom, that is, from totalitarian Eritrea and Morocco’s similarly totalitarian colony of Western Sahara, to the non-constitutional monarchies of the Arab Peninsula, to the military juntas of Egypt and Sudan, to the classical dictatorships of Chad and the Comoros, to the war-torn foreign protectorates of Iraq and Syria, to the failing states of Lebanon and Mali, and to the failed states of Libya and Yemen.

At present, Russian is the sole state-wide official (federal) language in the Russian Federation. Furthermore, this language functions in the co-official capacity in the six post-Soviet polities of Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Russian is also co-official in two autonomous regions, namely, Moldova’s Gagauzia and Ukraine’s Crimea. In the latter case it is a moot point, because from 2014 this Black Sea peninsula remains under Russian occupation. In addition, the co-official status of Russian is legally guaranteed in four de facto states that after 1991 the Kremlin militarily seized from Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine. In the first case it is Abkhazia and South Ossetia, in the second – Transnistria, and in the last one – Donbas.

Freedom and Statistics

Let us list the Russophone polities and territories from the least to the most free according to Freedom House. In the scale of 100 the lower the score the less free a given country is. Scoring the full 100, the Scandinavian states of Finland, Norway and Sweden are the most free in the world. The globe’s least free countries are South Sudan, Syria, Tibet, Turkmenistan, or North Korea, with the respective scores of -2, 0, 1, 2 and 3. Curiously, in the first case, the scale had to be extended by two points into the negative territory. Apparently, governments tend to be more inventive at repressing and limiting citizens than at furthering their freedoms. It is also interesting to remark that the Arabic-speaking country of Eritrea shares the extremely low score of 2 with the post-Soviet polity of Turkmenistan.

| Turkmenistan | 2 |

| Donbas | 5 |

| Crimea | 8 |

| Tajikistan | 9 |

| South Ossetia | 10 |

| Uzbekistan | 10 |

| Belarus | 19 |

| Russia | 20 |

| Transnistria | 22 |

| Kazakhstan | 23 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 38 |

| (Gagauzia) | (60) |

Unfreedom observed in the globe’s polities with Russian as an official or co-official language

(NB: Freedom House does not rank autonomous Gagauzia separately from Moldova, hence the score in the table is for the entire country)

In light of the unprecedented wave of repressions that followed the blatantly rigged 2020 presidential election in Belarus,[2] the country’s overall score is bound to drop to the low teens or even into the odious territory of single digits. Due to the demographic size of Russia at over 146 million inhabitants,[3] the overall freedom score for the Russophone world is 20. From the Kremlin’s perspective Turkmenistan with its score of 2 appears a bit too oppressive, whereas Kyrgyzstan too progressive at the score of 34. But the average score for all the Russian-speaking polities and territories without Gagauzia is 15, while 21 with the inclusion of this autonomous region of Moldova.

| Champions of freedom (scores: 90 and higher) | None |

| Free (scores: 50 and above) | Tunisia (70) |

| Partly free (scores: 20-49) | Lebanon (44), Jordan (37), Morocco (37), Algeria (34), Oman (23), Egypt (21) |

| Not free (scores: 19 and lower) | United Arab Emirates (17), Chad (17), Sudan (12), Yemen (11), Libya (9), Saudi Arabia (7), Western Sahara (4), Eritrea (2), Syria (0) |

Freedom and unfreedom in the Arabic-speaking world

(NB: Examples, not an exhaustive listing)

And again, the situation of what Moscow likes referring to as its ‘Russian World’ (Russkii Mir), is similar to that of the Arabicphone countries. The latter’s scores of civic and political freedoms fall squarely below 50, bar the lone exception of Tunisia with its now high score of 70. Lebanon with the score of 44 is followed by Jordan (37), Morocco (37), or Algeria (34) as partly free countries; while Oman (23), Egypt (21), or the United Arab Emirates (17) fall into the bracket of unfree regimes. In turn, quite a few Arabic-speaking countries score teens and single digits – for instance, Chad (17), Sudan (12), Yemen (11), Libya (9), Saudi Arabia (7), Western Sahara (4), Eritrea (2), or Syria (0) – which is a salient characteristic of oppressive regimes and countries at war. Due to its population of 102 million,[4] Egypt sets the trend across the Arabic-speaking world, which is still pulled downward by the oil-rich monarchies in the Arab Peninsula, so that the overall score hovers around 20 for all the Arabic-speaking countries.

At first, I thought that the Chinese-speaking states may be more similar to the case of the ‘Russian world,’ but not really. China’s huge demographic size of 1.4 billion[5] pushes the Sinophone area to the yet lower (or is it ‘higher’ from an autocrat’s perspective?) standard of unfreedom pegged at around Beijing’s own score of 10. Taiwan with its extremely high score of 93 is placed at the other end of the scale, as the Sinic champion of freedom. Freedom House also ranks China’s autonomous territories of Hong Kong (55) and Tibet (1). Should all these scores be included in the tally, the mathematical average for the Chinese-speaking countries is the respectable 34. However, the ongoing curbing of democracy in Hong Kong is bound to bring the polity’s score down soon.

| Champions of freedom (scores: 90 and higher) | Canada (98), Australia (97), Britain (94), New Zealand (92) |

| Free (scores: 50 and above) | USA (86), South Africa (79), Namibia (77), Botswana (72), India (71), Malaysia (52) |

| Partly free (scores: 20-49) | Kenya (48), Nigeria (47), Bangladesh (39), Pakistan (38), Zimbabwe (29), Brunei (28), Pakistan’s & India’s sections of Kashmir (28), Rwanda (22) |

| Not free (scores: 19 and lower) | None |

Freedom and unfreedom in the English-speaking world (including Commonwealth countries)

(NB: Examples, not an exhaustive listing)

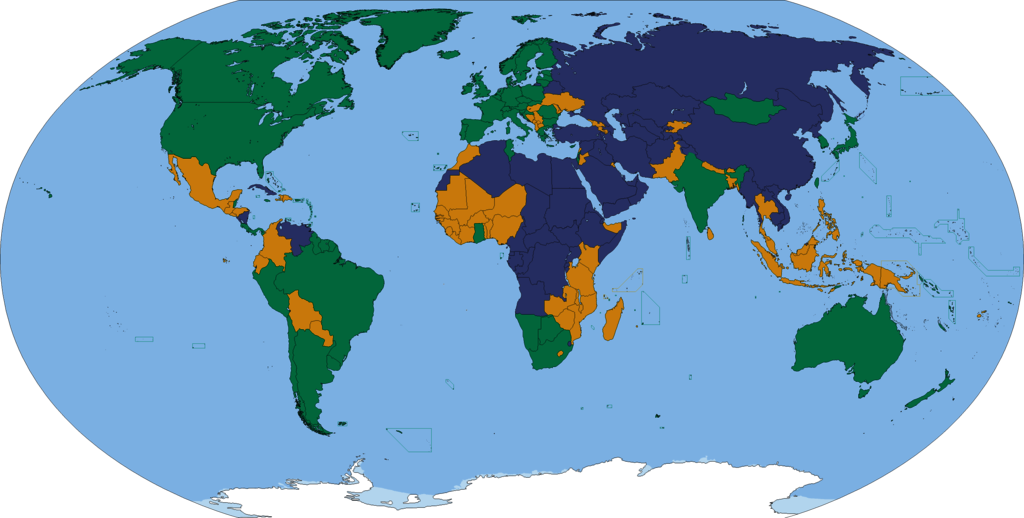

Britain (94) as the ‘mother country’ of the Anglophone world scores high on the ranking of civic and political freedoms. Yet, Canada (98) and Australia (97) still do better. Unsurprisingly, following the four years of Donald Trump’s presidency with its clearly pro-authoritarian leanings,[6] the United States’ ranking (86) dropped below the 90 threshold. The surprise is that from the perspective of the entire globe, even the most problematic English-speaking countries and regions score above 20. As a result, not a single Anglophone polity falls into the world’s group of the odiously least free polities. On the other hand, the low score of 20 is the norm or ‘golden mean’ for Russian- or Arabic-speaking. Yet, it appears to be utterly unacceptable in the English-speaking world, where it is seen as the rock hard bottom of unfreedom. Anglophone states and their inhabitants dare not to slide below this limit.

| Champions of freedom (scores: 90 and higher) | Canada (98), Luxembourg (98), Belgium (96), France (90) |

| Free (scores: 50 and above) | Senegal (71), Madagascar (61) |

| Partly free (scores: 20-49) | Niger (48), Mali (41), Mauretania (34), Cambodia (25), Congo (20), Vietnam 20 |

| Not free (scores: 19 and lower) | Democratic Republic of Congo (18), Cameroon (18), Chad (17), Laos (14), Central African Republic (10) |

Freedom and unfreedom in the French-speaking world (including Francophonie countries)

(NB: Examples, not an exhaustive listing)

Like in the case of Britain, France as the ‘parent country’ of the worldwide Francophonie, scores the respectable 90 in the ranking of civic and political freedoms. But Paris is outdone in this competition by the polities of Canada (98), Luxembourg (98) and Belgium (96), where French is co-official. Otherwise, Francophone states are quite evenly distributed across all the ranking’s categories of free, partly free and unfree countries. However, similarly to the case of the United Kingdom in the case of the Anglophonia, the norm and aspirational tendency in the French speaking world, as set by France, is toward the highest level of civic and political freedoms.

| Champions of freedom (scores: 90 and higher) | Uruguay (98), Spain (92), Chile (90) |

| Free (scores: 50 and above) | Argentina (85), Ecuador (65), Mexico (62), Guatemala (52) |

| Partly free (scores: 20-49) | Honduras (45), Nicaragua (31) |

| Not free (scores: 19 and lower) | Venezuela (16), Cuba (14), Equatorial Guinea (6) |

Freedom and unfreedom in the Spanish-speaking world (including Commonwealth countries)

(NB: Examples, not an exhaustive listing)

The same inclination is observed across the Spanish-speaking countries. Spain (92) and the high scoring South American states of Uruguay (98) and Chile (90) set the overall tone across the Spanish-speaking world. However, polities with Spanish as its official language are also spread across all the ranking’s categories of free, partly free and unfree countries. To a degree, the situation is repeated in the case of the Lusophone world, led by the ‘mother country’ of Portugal (96), as the group’s champion of civic and political freedoms. Lisbon’s example is gradually followed by Brazil (75), Timor-Leste (71), Mozambique (45), or Angola (32).

Nowadays, after the Germany-led and –perpetrated Holocaust of Jews and Roma, German is not a global language any more. Yet, German is western and central Europe’s language with the largest number of speakers at around 100 million. This language is official or co-official in Luxembourg (98), Belgium (96), Switzerland (96), Germany (94), Austria (93) and Liechtenstein (90). Unusually for ‘big languages,’ all these aforementioned polities where German is official or co-official are placed in the very same top league as champions of civic and political freedoms. Hence, in this respect, the German-speaking countries constitute the opposite pole to the global penchant for unfreedom, which is the well-established norm of politics and civic life across the Russian- and Arabic-speaking countries, including China.

But it was not always like that in the past. Things do change. During the 1930s and in the course of World War II, Germany and other German-speaking countries and territories as annexed, occupied and otherwise dominated by Germany, followed Berlin’s lead to totalitarian unfreedom, and eventually to perdition. Bearing in mind the Holocaust and the ravages of total war unleashed by Berlin on Europe and the world, the Third Reich probably would have scored -10 or lower in the Freedom House scale, should it be applied retroactively. Only Liechtenstein and Switzerland, which escaped German occupation and stayed away from the war, managed to preserve a respectable level of civic and political freedoms. However, it was the victorious Anglophone allies of Britain and the United States that firmly brought Austria and (West) Germany back into the fold of the globe’s free and democratic countries.

Blind Fate?

Is it a language itself that compels its speakers toward democracy and freedom or toward unfreedom and authoritarianism? Do Arabic and Russian share a characteristic that inherently pushes people to embrace dictatorships? Of course, not. Languages, like political ideas or states themselves, are constructs, that is, products of human ingenuity and labor. Neither nature nor a deity does gift people with these. It is humans and their groups who come up with ideas. Subsequently, they flesh up some ideas in the form of actual languages and polities. All of human ideas and their actualizations are artifacts of culture. The inanimate or DNA-based nature is unable to spawn any ideas or implement them in the form of artifacts.

Likewise, it is humans and their groups who decide which set of values should govern their societies (nations) enclosed in this or that polity. After such a decision has been taken, the adopted values are transmitted through the polity’s medium of official (main) language. Acting in line with these values, the citizens build, legitimize and maintain their state, society, politics, culture and economy, accordingly. Because the social reality is constructed and maintained through language and its use within a human group, with time a given state’s official (main) language also becomes the message. The language comes to symbolize these very values and principles adopted in a polity. The values and principles constitute the epitome of what is deemed as ‘normal’ in a polity (society), and thus become the norms of doing things political, social, economic, or cultural.[7]

In due course, these norms are imparted to future generations through education, and to all and sundry via the mass media and everyday social practices. People socialized in accordance with such norms since their childhood are unable to imagine that societies and states can be organized differently, in line with different values and principles. A person can develop such an insight only when she has a chance to sojourn and obtain education abroad in states that are constructed and run differently than her own country. A working knowledge of another languages is a must for the process to be successful. Yet, the nature of ‘big languages’ is such that they promote and reinforce monolingualism as a leading sociocultural norm. Speaking and being literate in a ‘world language’ opens unprecedented perspectives to an individual and makes it possible for him to communicate with anyone from hundreds of millions of speakers of this or that ‘world language.’ These opportunities are unavailable to people who use ‘small languages’ with speech communities ranging between several hundreds of thousands and several tens of millions of speakers. The former is the case of Maltese with 400,000 speakers, while the latter of Romanian with the 20 million speakers.

As a result, speakers of ‘small languages’ tend to acquire ‘big languages’ for the sake of improving their educational, employment or social opportunities. The entailed phenomenon of multilingualism is widespread among spears of such ‘small languages.’ On the other hand, speakers of ‘big languages’ do not enjoy a similar motivation, and the overwhelming majority of them never venture outside the monolingual frontier of their ‘big language.’ This facilitating but in reality limiting monolingualism tightly isolates them from the rest of the globe’s population. Hence, the ubiquitous simile of the ‘big language X-speaking world.’ The speech community of a ‘big languages’ tends to become a world unto itself; indeed, a separate planet of culture, politics and social relations.

It is hard, if not impossible to ‘travel’ from such a ‘linguistic planet’ of a ‘big language’ to other planets of languages with speech communities of variegated sizes. Yet, the speaker of a ‘big language’ only reluctantly and rarely dares to peer outside of her monolingual world. This customary isolation allows the powers that be to promote and reinforce effectively values and norms typical to the ‘linguistic planet’ of a given ‘big language.’

Taking Control

Obviously, such norms and values evolve and may be altered even quite rapidly, as the aforementioned case of the German-speaking world proves. German-speakers subscribed to and acted in line with radically different sets of political and social values that changed dramatically between 1940 and 1950. In the span of a single decade democracy and respect for human rights steadily replaced totalitarianism and genocide as the prevailing social and political norm.

The Ukrainians set out on the course toward democracy, only after making sure in 2014 that Russian would not become a co-official language in their country. Otherwise, the danger was, that Russian would have further marginalized this state’s national language of Ukrainian, as it had already happened in the case of Belarusian in Belarus, where Russian had become official in 1995. The dominance of Russian as the main language of public life in Belarus constitutes a proverbial ‘conveyor belt’ for the swift transfer of values and norms from the Russian world into this country. In contrast, the unchanged use of Russian exclusively as a minority or auxiliary language, combined with the loss of predominantly Russophone Crimea and Donbas, stalled this aforementioned ‘conveyor belt’ of values and norms from the Russian world into Ukraine. Ukraine prefers its own norms and values, or their likes from the west, as epitomized by the English- and French-speaking worlds. As a result, the Ukrainians did not allow themselves to be ‘gulped down’ by the Russian world.

No language is a neutral transmitter of ‘pure’ (context-free) information. Speech communities (nations, states, human groups) shape and re-shape their languages as much as these languages – through values encoded in them – reinforce the accepted norms in their respective communities. What is all too rarely realized is that the primary function of languages is bonding humans into groups, not a mere communication.

Hence, the formal choice of an official language for a state is not an innocent pastime. It entails all kinds of consequences. At 35 percent[8] and 30 percent,[9] respectively, the post-Soviet countries of Latvia and Estonia have a bigger percentage of Russian-speakers in their populations than Kazakhstan (24 percent[10]) or Tajikistan (half a percent[11]), where Russian is co-official. Apart from Russia, among the states with Russian as a co-official language, only Belarus has a higher percentage of Russian-speakers (70 percent[12]) than Latvia and Estonia. However, similarly to Ukraine, Estonia and Latvia decided not to accord the status of a co-official language to Russian. It was a conscious choice taken for the sake of preventing the entailed marginalization of Estonian and Latvian on the one hand, while on the other hand, in order to curb the spread of the Russian world’s authoritarian ‘values’ to both countries. Belarus is a cautionary tale on where to the marginalization of the state’s national language – in this case, Belarusian – may lead. It has allowed for the unchecked and swift transfer of norms and values from Russia to Belarus, as channeled through the Russian language. As a result, after a quarter of a century, the Belarusian language is hardly ever heard in everyday life anywhere in Belarus,[13] while many Russians, and even Belarusians, see this country as a Russian province.[14]

The score of civic and political freedoms is much higher in Estonia (94), Latvia (89), or for that matter in Ukraine (62) than in Russia or any officially Russophone country from across the Russian world. In addition, both Estonia and Latvia are member states of the European Union and NATO. The entailed high levels of freedoms, combined with the living standard considerably higher than that observed in the Russian Federation (let alone Tajikistan) convince Russian-speakers to stay put in Estonia and Latvia. On the other hand, many already left Turkmenistan[15] or Uzbekistan[16] for Russia.

Moscow criticizes Latvia for not recognizing Russian as a co-official,[17] or minority language.[18] But Latvian politicians are well aware that Russian is an imperial language, and that it functions as the Russian world’s conveyor belt of values and norms.[19] So Riga keeps limiting the use of Russian as a medium of education[20] and in 2020 (alongside Estonia and Lithuania) banned rebroadcasts of Russian television from the Russian Federation, because it spreads the Kremlin’s propaganda.[21] The aim of all these measures is to propagate Latvia’s democratic norms and values, as symbolized by and communicated through the Latvian language. In addition, as a stop-gap measure, for the last two decades, Riga has increasingly taken control of the Russian language as de facto employed across the country’s territory,[22] for example, through the provision of Russophone mass media produced in Latvia by Latvian citizens.[23] These mass media provide information from Latvia’s perspective not Moscow’s. Riga makes sure that like other Latvians, the country’s Russian-speakers are brought up, educated and live in the world of Latvian and EU values, as characterized by democracy, and full civic and political freedoms.

August 2020

[1] https://freedomhouse.org/countries/freedom-world/scores

[2] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/aug/12/belarus-protesters-and-police-clash-for-third-night-as-eu-threatens-sanctions

[3] https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/russia-population/

[4] https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/egypt-population/

[5] https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/china-population/

[6] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/jul/23/trump-authoritarianism-portland-cbp-election

[7] Cf Karl W. Deutsch. 1953. Nationalism and Social Communication: An Inquiry into the Foundations of Nationality. Cambridge MA: The M.I.T. Press.

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_Latvia#Languages

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_Estonia#Languages

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_Kazakhstan#History_of_ethnic_composition

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_Tajikistan#Ethnic_groups

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Languages_of_Belarus#Development_since_the_collapse_of_the_Soviet_Union

[13] https://belarusfeed.com/belarus-explained-belarusian-language/

[14] https://www.euractiv.com/section/europe-s-east/opinion/belarus-should-not-be-a-province-of-the-russian-neo-empire/

[15] http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/asia-pacific/3007598.stm

[16] https://www.rferl.org/a/1100593.html

[17] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-17083397

[18] https://www.euractiv.com/section/languages-culture/news/russian-speakers-excluded-from-eu-brochures-in-latvia/

[19] https://neweasterneurope.eu/2019/05/08/estonian-russian-if-or-when/

[20] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-43626368

[21] https://www.politico.eu/article/latvia-bans-rt-russian-television-channel/