Tomasz Kamusella: Antisemitism in Communist Czechoslovakia

Antisemitism in Communist Czechoslovakia

Tomasz Kamusella

University of St Andrews

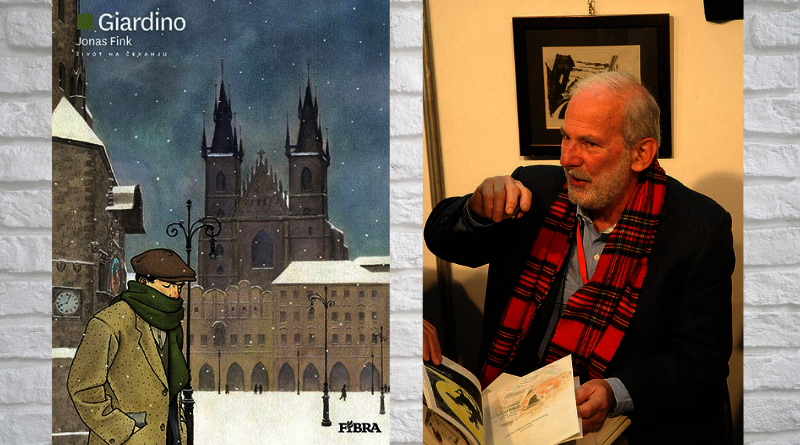

review of: Vittorio Giardino. 2018. Jonas Fink. Život na čekanju. [Jonas Fink: A Life on Hold; Italian original: Jonas Fink. Una vita sospesa, translated into Croatian by Ružica Babić] Zagreb: Fibra. 328pp. ISBN 9789533213804. Hard cover, full color. Price: 270KN.

review of: Vittorio Giardino. 2018. Jonas Fink. Život na čekanju. [Jonas Fink: A Life on Hold; Italian original: Jonas Fink. Una vita sospesa, translated into Croatian by Ružica Babić] Zagreb: Fibra. 328pp. ISBN 9789533213804. Hard cover, full color. Price: 270KN.

Giardino – as he signs his works and as the author is known among aficionados of graphic storytelling – is a grand old man of this until recently underappreciated cross of art and fiction, or so-called ‘comics.’ Nowadays, this genre is more appropriately referred to as graphic fiction or graphic novel. Born in 1946 in Bologna, Giardino graduated as an electrical engineer in 1969, and worked in this profession until 1977. Then, almost overnight, he turned to drawing professionally. In 1978 his first graphic fiction book appeared, after having been serialized previously in the weekly La Città Futura, published by the Italian Communist Youth Federation (Federazione Giovanile Comunista Italiana). It is not for nothing that his home city is nicknamed La Rossa (‘The Red One’). Thus, Giardino became a full-fledged fumettista, or a drawer of ‘funnies’ (cartoonist). With time he created several popular characters, for instance, the hardboiled detective Sam Pazzo or the unassuming hero-cum-undercover agent Max Friedman, who once fought against the fascists in the Spanish Civil War. The most popular setting of Giardino’s graphic stories is interwar Central Europe, extending liberally from Budapest to Istanbul, with the interwar Spanish Republic thrown in for an equal measure. What has consistently attracted hosts of readers in Italy, the Low Countries, France, Spain or North America to Giardino’s stories is a paunchy plot, alongside the ‘clear line’ (linia chiara) that both gives his images a hard-nosed realist look, but also makes them almost dreamy in the fashion of Japanese wood block prints. The early master Katsushika Hokusai’s (1760-1849) famous works (for example, Great Daruma [1817] or Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji [1829–1832]) immediately come to mind. Unsurprisingly, Hokusai’s books of prints are lauded as the source of today’s manga, or the Japanese-style graphic fiction. Hence, the claim that Giardino borrowed this particular style of drawing from Hergé (nom de plume of Georges Prosper Remi, 1907-1983), or the creator of The Adventures of Tintin, is an overstatement. What is more, technical drawing, as expected from an engineer, was also a factor in the case of Giardino.

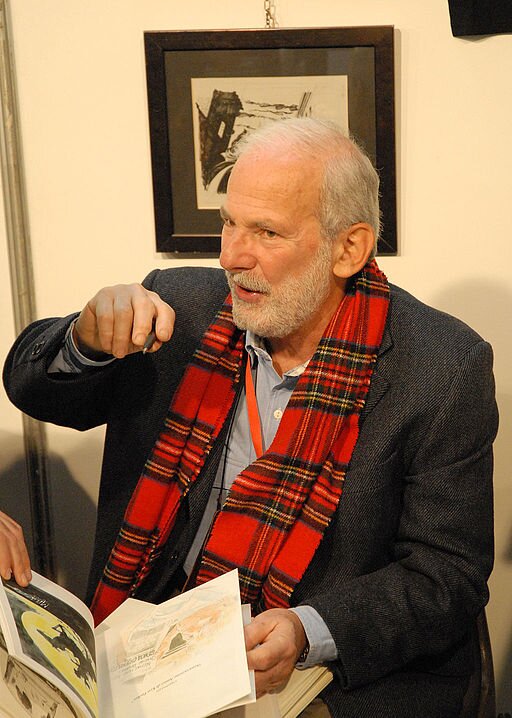

Vittorio Giardino in 2010[1]

Labelling Giardino as a cartoonist of sensational and adventure comics did him much disservice, though in general it was the way in which he earned a living, including the beautifully drawn and deceptively Freudian in their character erotic stories about Little Ego, or a nubile girl in search of sexual fulfillment. In the market of pulp literature, no attention has been paid to detail, resulting in numerous slapdash English translations of Giardino’s graphic novels during the 1980s and 1990s, which seemed to confirm the generalized opinion that comics were a ‘low’ form of culture. In the English-speaking world the tide turned with the 1991 publication of Art Spigelman’s (1948-) graphic novel Maus on the harrowing subject of the Holocaust and Holocaust survivors. The exquisiteness of Giardino’s unique fusion of drawing and storytelling was more readily appreciated in his native Italy, France, the Benelux countries, or in Spain.

The writer also made a conscious effort to leave the comics ghetto by focusing on more extensive graphic novels with a solid grounding in 20th-century history. Max Fridman: No Pasaràn (2000-2008) offers a potent criticism of fascism and Nazism, thanks to the plot line set against the backdrop of the Spanish Civil War. Earlier, just two years after the fall of communism in Europe, in 1991, Giardino created a brand-new character; a boy living in stalinist Prague. He decided to write-and-draw a genuine graphic Bildungsroman, rather than to stick to typically comics characters who are adult, do not age, or have any known childhood origin. With this novel project, as an artist in his own right, Giardino could speak the truth about Soviet totalitarianism. For the writer it was also a very personal with illusions of the past. The unpalatable reality of the Soviet crimes – as revealed by the Soviet Invasions in Hungary (1956) and Czechoslovakia (1968), and with renewed force after the collapse of the Soviet bloc – shattered his ideological commitment to socialism. The aforementioned boy’s name is Jonas Fink. In 1950, his father, Dr Arthur Fink, a lawyer was suddenly arrested and condemned to two a decade in prison with no right to correspondence or family visits. From one day to another, Jonas and his mum, Edith, are left with no means of earning a living in a grandiose apartment. They need to sell the grand piano, books and furniture merely to survive. But even this lifeline is taken away from them, when the authorities requisition their ‘bourgeois’ apartment and prevent Edith from doing any other job but manual work, for which she is not suited. Jonas’s carefree teenage years are definitely over, marred by all these tragic and essentially inexplicable events. Yet, what pains Jonas even more is that he was abandoned by his school friends, who now see him and his family as ‘people’s enemies.’ Soon, however, there is no more education for him, either, since the socialist fatherland does not let class enemies’ children to progress to secondary school. And what is the family’s ‘crime,’ none other than the fact of being assimilated and non-religious Jews. The authorities take care never to admit that this is the problem.

In 1948, following the founding of Israel, Stalin (1878-1953) began preparing a purge against Jews in the Soviet Union that culminated in the so-called ‘Doctors’ Plot’ (1951-1953), and was stopped half-way by the tyrant’s death. The Soviet satellites were obliged to follow suit, including Czechoslovakia, where the show trial against the country’s leader of Jewish extraction, Rudolf Slánský (1901-1952), ended in his summary execution. In this manner, antisemitism became a significant modus operandi of the Soviet bloc, which was eerily reminiscent of the suppression of Jews and their rapid exclusion from society in Germany, following Hitler’s (1889-1945) rise to power in 1933. After the wartime Holocaust, no another genocide of Jews was planned against Holocaust survivors in the Soviet bloc, but Jews were either expelled or harassed into hiding and erasing their identity. But this was never sufficient, because the authorities did know who ‘really’ was a Jew, and each of them was now guilty of concealing their identity. Stalin branded Jews as ‘rootless cosmopolitans,’ alleging that ‘by nature’ they were unable to become patriots. Hence, each Jew must always be a traitor of their fatherland, whenever the communist powers that be decide so.

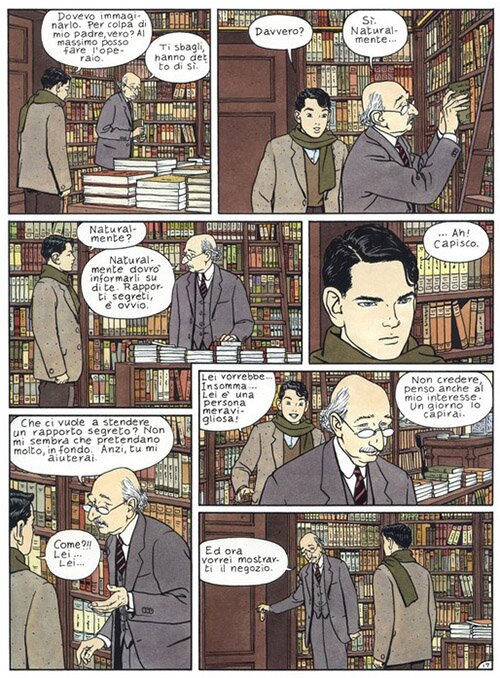

Some slapstick scenes that brighten the darkening mood in the novel’s Part I ‘Childhood’ (44 pages) disappear from Part II ‘Youth’ (96 pages). The suitably serious plot commences, a bit enlivened by the everyday humor of workers. They are adept at duping their clueless superiors, who demand overshooting the work plan several hundred percent over, with no extra pay on the offer. With the coming of age, Jonas needs to help her prematurely aged mum, and finds a job as a bricklayer. The experienced and understanding worker Slavěk inducts him to this world of manual labor that keeps to itself and remains distrustful of communist party apparatchiks. His tenacity and intelligence earns Jonas much good will. Many still remember and clandestinely respect his father, so they choose to come to Joans’s succor in this new totalitarian reality. Eventually, he becomes a shop assistant in one of the few remaining private bookshops. The owner, Mr Pinkel, trusts Jonas, who soon makes this bookstore into his university, reading voraciously, satisfying customers’ varied wishes, and earning a living. Due to stringent censorship, the precious access to books gets Jonas attention and respect of his former colleagues, who are now already at university. Zdeněk heads an informal discussion group securing various forbidden books from his father who is a translator with contacts in the West. Mr Pinkel is part of the tenuous supply chain, so Jonas also has a peek and can help his new friends secure interesting titles and transcripts of unpublished translations of foreign works. One of the students is Tatjana, a daughter of a Soviet diplomat in Prague. She and Jonas fall in love. Thanks to the Czechoslovak secret police who have spied on the Finks since the turn of the 1950s, Tatjana’s parents know well that she is romantically involved. They deem it as a danger to their family and careers, so arrange for sending Tatjana back to the Soviet Union to complete her education. This nadir in Jonas’s life is deepened by an official letter with the information that his father was condemned to yet another ten years in prison.

Jonas and Mr Pinkel[2]

Jonas and Mr Pinkel[2]

The graphic novel’s two initial parts appeared in a rapid succession, that is, in 1994 and 1997. However, Giardino aimed still higher. While working on Part III ‘The Bookseller of Prague’ (160 pages), the artist also remastered the images and lettering in the novel’s two initial parts. Otherwise, time was scarce, because he had to finish another graphic novel Max Fridman: No Pasaràn. As usual, it provided him with bread and butter, but also allowed Giardino to perfect his drawing and plotting techniques. That is why, Jonas Fink is a crowning achievement of both his art and career. The story of Part III zooms on the acme of high hopes, as heralded by the Prague Spring. Soon, by the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia proved it to be a false dawn. Communist leader Alexander Dubček’s (1921-1992) ‘socialism with a human face’ turned out to be an impossibility. The Soviets would not have it. Jonas and his friends enter adulthood, and start careers. Jonas is content, having taken over the day-to-day running of the bookstore. In early 1968 stalinists low lie, but behind closed doors keep scheming with Soviet overseers against Dubček’s government. Compensations are promised for victims of stalinist crimes and repression. In an archive, Jonas finds out that his father died two years into his second term, or in 1962. The family was never informed. Edith, due to years of grief suffers mental health problems and is confined to a sanatorium. She keeps knitting warm woolen socks for her husband whom she will never meet again.

Jonas visiting his parents in the Jewish cemetery

Tatjana, as a trusted Soviet journalist, is back to the scene of the political rejuvenation of communism in Prague. This hopeful period, as also marked by the student protests and sexual revolution in Italy and France, coincided with the end Giardino’s university studies. The subsequent disaster of Soviet tanks in Prague and the West’s disillusion with the events, yielded the Anni di piombo (Years of Lead) in Italy, where for two decades left- and right-wing terrorists battled one another and the Italian state, as well. Meanwhile in Prague, at long last Tatjana and Jonas consume their love. But it is not to last. When the Warsaw Pact’s ‘fraternal’ forces stream to Czechoslovakia, stalinists are back in power with full Soviet support behind them. The suppression of Dubček’s ‘traitors to communism’ and former ‘people’s enemies’ resumes. Zdeněk is killed by brutal investigators. Tatjana writes a ‘dialectically correct’ article on the invasion whitewashing the ugly reality. Jonas takes no chances and leaves for the West, when the border still remains open. In 1990, several months after the Velvet Revolution, he is back to Prague, together with his French wife, Sylvie, and their son, Didier. They visit Jonas’s parents finally reunited in the Jewish cemetery. He could not attend the funeral of his mother, when Edith died two years after his departure. Subsequently, Jonas and the old friends meet again. Now they hope for democracy, stability and prosperity in postcommunist Czechoslovakia, not realizing the tribulations of the 1993 breakup of Czechoslovakia that lurk round the corner. Tanja also paid a heavy price. For her equivocal condemnation of the Prague Spring she was exiled to a town somewhere in the Urals. Pinkel’s bookstore became a run-of-the-mill clothes shop. Ideas cheapened, money is what counts. Communist spies who blighted Jonas’s childhood and youth live out their old age on comfortable pensions in the suddenly prosperous and gaudy Prague of rapacious capitalism. On the side, so that no one would overhear, they still hate Jews, ‘these cuckoos,’ a folksy term for ‘rootless cosmopolitan.’

Zdeněk killed during investigation

The novel in its polished single volume edition is a triumph, two decades in making and a quarter of a century in gestation. This is a Maus about communist totalitarianism, which many mistakenly see as ‘not so bad.’ Meanwhile, the People’s Republic of China proposes that its communist system of total IT-enabled surveillance is the way of a ‘bright and stable tomorrow,’ populated by ‘harmonized societies,’ with un-harmonize-able individuals either thrown into forced labor camps or summarily executed (vital organs conscientiously cut out from their bodies for commercial transplants). The integral edition of the novel’s Italian original was published in 2018. Already later this year a Croatian translation appeared, thanks to close cultural and historical connections between the two countries.[3] Curiously, to this day no Czech translation has been published. Editions in other languages followed but rather slowly, in 2019, in Dutch, German and Spanish. However, the Dutch edition is a bibliophile affair of a mere 150 numbered copies.[4] The French edition is planned for early 2021. The uptake of Giardino’s openly adventure graphic novels was much faster. Serious fiction on post-Cold War Europe’s fundamental values of freedom, democracy and human rights takes time, both to create and mature, and also to be absorbed and appreciated by perusers. Giardino’s unwavering loyalty to these values and fidelity to historical detail (see the sketches and documentary photographs in the book’s appendix), peppered with references to literature, are sure to eventually win the reader’s heart and mind for this opus magnum of graphic fiction. It is a towering testament to Giardino’s art and to the best in Europe’s culture and politics. Let us hope that the Europeans will remember about their achievements and will not give up on them in pursuit of a Chinese dream.

February 2021

[1] Jollyroger & Frieda. 2010. File:Lucca2010 Giardino.jpg. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lucca2010_Giardino.jpg

[2] Andrea Antonazzo. 2018. Storia di “Jonas Fink”, l’opera ventennale di Vittorio Giardino. Fumettologica. 1 Mar. https://www.fumettologica.it/2018/03/jonas-fink-vittorio-giardino-fumetto/

[3] 24. Sa(n)jam knjige u istri. 2018. Pula: Dom hrvatskih branitjela. http://arhiva.sanjamknjige.hr/hr/2018/program/dnevnik-sajma/3-prosinca/

[4] Jonas Fink – Integraal. 2019. https://www.vlaamsstripcentrum.shop/strips/jonas-fink-integraal