A Belarusian 1Q84?

A Belarusian 1Q84?

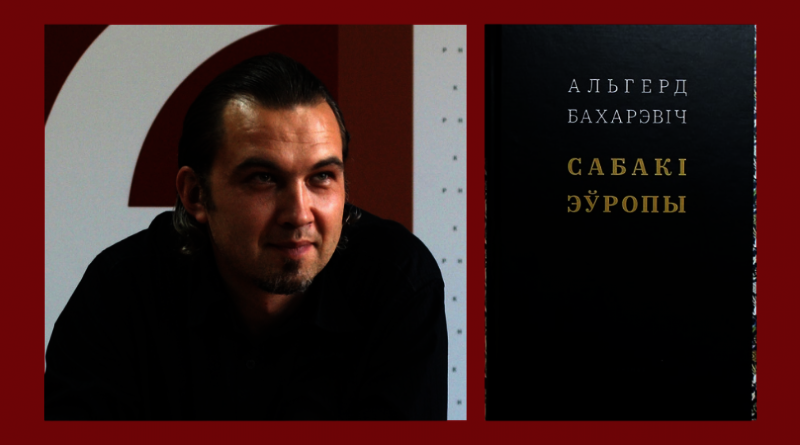

(review of Альгерд Бахарэвіч. 2017. Сабакі Эўропы. Вільня & Мінск: Логвінаў / Alhierd Bacharevič. 2017. Sabaki Eŭropy [Dogs of Europe]. Vilnius & Minsk: Lohvinaŭ, 896pp)

Tomasz Kamusella

University of St Andrews

Bacharevič is considered to be an enfant terrible or even a ‘bad boy’ of present-day Belarusian literature. The country’s movers and shakers in the world of belles lettres grudgingly take notice of the sheer beauty and innovativeness of his prose and plotlines, but choose to slight the author, for instance, by denying him the ultimate first place in the annual Jerzy Giedroyc Literary Award (Літаратурная прэмія імя Ежы Гедройца Litaraturnaja premija imia Ježy Hiedrojca) for Belarusian-language writers. Recently, Bacharevič finally took offence – rightly so – and publically requested that the autobiography on his youth as a punk rock star and poet, Мае дзевяностыя Maje dzievianostyja (My 1990s, 2018) be excluded from the 2019 competition. For him Belarusian-language literature is neither about securing a job provided by the state-approved Union of Belarusian Writer (Саюз беларускіх пісьменнікаў Sajuz biełaruskich piśmiennikaŭ), nor about contributing to the ethnolinguistic Belarusian national movement, currently quite suppressed in Aljaksandar Łukašenka’s authoritarian and overwhelmingly Russophone Belarus in a Union State with Russia.

Bacharevič believes that writers are to write as best as they can in a language of their choice. This principle dictated his conscious decision in secondary school at the turn of the 1990s to start speaking and writing exclusively in Belarusian. At that time this language was considered an unbecoming ‘peasant patois.’ It was believed that in Belarus one could be ‘modern and progressive’ only in Russian. The author’s parents and friends accepted his ‘peculiarity’ as fascinating, because he married it with avant-garde poetry (as a member of the irreverent Бум-Бам-Лит Bum-Bam-Lit literary movement) and unwavering loyalty to the freedom of thought. On top of that all of the mentioned persons had a degree of passive command of Belarusian, while the generation of grandparents who had moved to Miensk after World War II still spoke it. From the perspective of the central Europe of ethnolinguistic nation-states, it is normal that citizens should be fluent in the national (official) language of their country. Not so much in Soviet Belarus, where for the sake of making it into an integral part of the classless Soviet people (народ narod), the Belarusians were untaught to use their language. Belarus is the sole post-Soviet state, where a minority – barely a tenth of the population – speak the national language. Kazakhstan was on the same path to homogenous Russophone-ness, with a third of the inhabitants fluent in Kazakh, but this trend was reversed, so that about 70 percent of the inhabitants speak this language. Unlike in Belarus in the case of Belarusian, a good working command of Kazakh is a must when one applies for a job in civil service or in the management of a private company.

A similar reversal of Russification of public life was attempted in freshly independent Belarus between 1991 and 1995. A teacher who did not appreciate young Bacharevič’s choice of Belarusian as his sole language of communication and coursework might have him punished or even excluded from school. But the winds of history temporarily turned the table in favor of Belarusian and the national white-red-white flag, which the future author proudly brandished on his leather jacket. After the 1995 proclamation of Russian as an equal co-official language in Belarus, his educational choices were limited to the Department of Belarusian Language and Literature at Maxim Tank Belarusian State Pedagogical University. Elsewhere, Russian remained or was re-introduced as the sole or dominant language of instruction. (To this day there is no Belarusian-language university in Belarus.) Subsequently, after graduation, Bacharevič intellectually and socially suffocated working as a school teacher of Belarusian language and literature. Intermittent stints as a journalist for a factory newspaper’s Belarusian-language paper gave him more freedom, but the freedom of speech was soon over in Belarus. At that time he decided to devote himself fully to literature and earn a living solely by writing. When the repressiveness of the Łukašenka regime reached its new heights at the beginning of the 21st century, the writer was compelled to seek asylum in Germany in 2007. But the West’s fickle sympathy and support for refugees from the ‘last dictatorship of Europe’ soon waned. Again, in 2013, Bacharevič had no choice but to return to Miensk, if he was to remain loyal to literature as his sole profession. Luckily, after ‘winning’ his fourth term in office as president in 2010, Łukašenka loosened the screw of control over culture and the Belarusian-language intelligentsia.

A similar reversal of Russification of public life was attempted in freshly independent Belarus between 1991 and 1995. A teacher who did not appreciate young Bacharevič’s choice of Belarusian as his sole language of communication and coursework might have him punished or even excluded from school. But the winds of history temporarily turned the table in favor of Belarusian and the national white-red-white flag, which the future author proudly brandished on his leather jacket. After the 1995 proclamation of Russian as an equal co-official language in Belarus, his educational choices were limited to the Department of Belarusian Language and Literature at Maxim Tank Belarusian State Pedagogical University. Elsewhere, Russian remained or was re-introduced as the sole or dominant language of instruction. (To this day there is no Belarusian-language university in Belarus.) Subsequently, after graduation, Bacharevič intellectually and socially suffocated working as a school teacher of Belarusian language and literature. Intermittent stints as a journalist for a factory newspaper’s Belarusian-language paper gave him more freedom, but the freedom of speech was soon over in Belarus. At that time he decided to devote himself fully to literature and earn a living solely by writing. When the repressiveness of the Łukašenka regime reached its new heights at the beginning of the 21st century, the writer was compelled to seek asylum in Germany in 2007. But the West’s fickle sympathy and support for refugees from the ‘last dictatorship of Europe’ soon waned. Again, in 2013, Bacharevič had no choice but to return to Miensk, if he was to remain loyal to literature as his sole profession. Luckily, after ‘winning’ his fourth term in office as president in 2010, Łukašenka loosened the screw of control over culture and the Belarusian-language intelligentsia.

Bacharevič’s return to Belarus swiftly followed by his second marriage to the Belarusian-language poet Julia Cimafiejeva reinvigorated his writing. In 2014, two volumes of his essays were published, alongside the novel Дзеці Аліндаркі Dzieci Alindarki (Alindarka’s Children). It is a veritable road and GULAG story of unrequited love to women and language, exquisitely mixed with the modernized fairy tale ‘Hansel and Gretel.’ This effort resulted in a scathing satire on state-approved Belarusian-language literature and on the authorities’ implicit decision to fully replace Belarusian with Russian in all aspects of public life. A command of Belarusian became a ‘medical condition’ that had to be cured with Russian. On the other hand, the book is a highly readable page-turner, equally enjoyable when one has no background knowledge of Belarus for teasing out all the aforementioned nuances.

The following year, in 2015, Bacharevič upped the ante with Белая муха, забойца мужчын Biełaja mucha, zabojca mužčyn (White Fly, Men Killer). It is an unprecedented feminist roller-coaster of a novel that pokes fun at the continuing post-Soviet-style patriarchalism, which magnanimously designates 8 March as the International Women’s Day, but keeps all the year’s remaining 355 days as the almost never-ending holiday of machismo: women live only to serve their benevolent men and patriarchs. In the novel a novel the current reinvention of this patriarchalism in the anachronistic guise of ‘traditional Belarusian nobility’ (шляхта šliachta) becomes the butt of ridicule. An underground group of feminist paramilitaries seize the just renovated castle-cum-museum (ostensibly, the Belarusian UNESCO World Heritage site of the Radziwiłł castle complex in Mir) and take all the male tourists and staff as captives, alongside the women who refuse any liberation from the shackles of patriarchy. Drunk Russian male tourists rioting inside and valiant Belarusian KGB officers (all males, as well) ‘liberate’ the male visitors and their pro-patriarchy spouses from this almost biblical ‘female captivity,’ which for a brief moment afforded a hope for more equitable and inclusive Belarusian culture and society. The story is told by the male narrator through the lens of Gulliver’s voyage to Brobdingnag. He found himself safe and fulfilled in this world briefly run by women larger than patriarchal life.

The topics of illiberalism as symbolized by the concentration camp and of relentless and unthinking patriarchalism as illustrated by the subservient roles of women are at the heart of Bacharevič’s first two novels Сарока на шыбеніцы Saroka na šybienicy (Magpie on the Gallows, 2009) and Шабаны. Гісторыя аднаго зьнікненьня Šabany. Historyja adnaho źniknieńnia (Šabany: The Story of One Disappearance, 2012). They are longer (classified as раманы ramany in Belarusian), much darker and more avant-garde in the manner of story-telling than the two aforementioned later novels (seen rather as аповесьці apovieści in Belarus). But both sparkle with wry wit and are a pleasure to read. However, in Belarusian and arguably in post-Soviet fiction, Saroka na šybienicy offers the most incisive treatment of the shock of societal, economic political, cultural and technological change, as observed and experienced, from the early 1990s to the turn of the 21st century, by the inhabitants of anonymous ‘socialist quarters’ of depressingly identical concrete blocks of apartments, nowadays plagued by anomy, inequality, crime and despair. Šabany, among others, probes into such an eponymous city quarter, the largest in today’s Miensk. However, the author’s attention is turned to the dark and still unacknowledged recent history of this place, which used to be the location of the easternmost and third largest nazi death camp of Maly Trostinez (Mały Traścianiec). Unfortunately, to this day, Belarusian literature remains silent on the Holocaust of Jews and Roma. Belarus’s official policy of commemorations is squarely focused on the Soviet-style militaristic celebrations of the mythologized ‘Great Patriotic War.’

Individuals do not count in ‘large politics,’ but for Bacharevič literature must be about real-life persons, not any ‘historical processes,’ ‘masses’ or ‘great historical heroes,’ with whom school textbooks of history are littered. Otherwise, it is no longer literature, but propaganda, not writing but ‘producing’ novels in accordance with the official plan that requires five pages of a ‘literary work’ per a working day. Bacharevič is against the Soviet-style ‘productive character’ of literature or its subservient role to the building of a Belarusian nation. Literature is about the discovery and creation of beauty, freedom, the unexpected and love. Nothing would do short of this principled benchmark. While in German exile, Bacharevič re-read the canon of Belarusian literature, and sorted nationalist and socialist realist chaff from Literature with the capital L. In Гамбурскі рахунак Бахарэвіча Hamburski rachunak Bachareviča (Bacharevič’s Hamburg Account, 2012), Bacharevič gives engaging portraits of 50 Belarusian authors from the last two centuries, and is appalled to find out that only four women made it to this relentlessly patriarchal pantheon, namely, the first Belarusian feminist Цётка Ciotka (that is, Ałaiza Paškievič), poet Natałlia Arsieńnieva, the sole female member of the Belarusian government in exile Łarysa Hienijusz, and lyricist Jaŭhienija Janiščyc. Subsequently, Bacharevič wrote the unduly Sovietized and Russified Belarusian literature back into its historically and culturally central and western European context, by closely observing it through the prism of Belarus’s numerous links with Paris in his bravura essays gathered in the volume Бэзавы і чорны. Парыж праз акуляры беларускай літаратуры Bezavy i čorny. Paryž praz akuliary biełaruskaj litaratury (Lilac and Black: Paris Through the Prism of Belarusian Literature, 2016). Finally, in Ніякай літасьці Альгерду Б. Nijakaj litaści Alhierdu B. (No Mercy for Alhierd B., 2014), the author spelled out his uncompromising understanding of literature, the role of writer, Belarusian history and liberty.

Yet, hardly has Bacharevič’s ambitious oeuvre been noticed outside his native Belarus, and even in the country only Belarusian-language readers appreciate his stunning achievements. On the other hand, many fellow writers keep denying this success and even denigrate the author for the fact that he singlehandedly revaluated the Belarusian canon in line with the adopted principles, and reinvented Belarusian literature in his own books, safely beyond the state’s control and without bowing to Soviet and national sanctities. For Bacharevič literature is a goal in itself, its value and importance to be decided by readers alone. Obviously, his two famous parallel essays on the bright and dark sides of the classic pre- and Soviet poet Janka Kupała generated much criticism. All public attention zoomed on Bacharevič’s analysis how this poet allowed himself to be made into a soulless Soviet ‘engineer of souls.’ State-approved officials of Belarusian literature and culture could not forgive Bacharevič this slight. They were unable to grasp understand that a true writer must remain loyal to the truth and beauty, and that each new generation of poets and novelists must commit symbolic patricide (and matricide) in order to find their own way for the sake of reinvent and rejuvenating literature, rather than keep plodding on as boring epigons of a previous epoch.

This understanding of what writing is about, patiently percolated through the experience of Bacharevič’s early avant-garde novels, and finally was made eminently readable, thanks to innovative ways of story-telling developed in his later novels. With these achievements under his belt, in 2017, Bacharevič came back to the literary scene with an unprecedented literary big bang on a European scale. My first reaction after the breathless read through the thick tome (which took almost three weeks, due to my initial lack of facility in reading the Belarusian Cyrillic), was: Wow!, that is the European reply to Haruki Murakami’s 1Q84 (2009-2010). I know that Bacharevič does not approve of the famous Japanese writer’s prose devoid of most cultural references. Murakami chose this method in order to make his books more readily accessible to the global reader, so that they could become part of the American-style pop culture. This culture, of which the Japanese writer and his peers were enamored in their youth during the 1970s. Once Murakami remarked that he wrote his early novels first in English and then translated into Japanese for the sake of achieving this desired goal.

Bacharevič’s method is different. In spite of the Russophone reality of his childhood in Soviet Belarus, and the post-1995 Russifying pressure, he remains loyal to Belarusian as the medium of writing, and actively reinvents this language by uncovering its Europe-wide historical and cultural connections. With liberty as the lodestar of his values, Bacharevič engages with the latest discourses of European and global culture and politics, thanks to his fluency in German, French, Polish and Russian. Some propose that these ‘dogs’ in the title of Sabaki Eŭropy refer to the ‘small states’ of central and eastern Europe. I beg to disagree. Bacharevič wrote this novel during and in the wake of the so-called 2015 ‘migrant crisis,’ when almost 2 million refugees arrived in the European Union, and half of them headed to Germany. But this number is less than a half of a percentage point of the Union’s population of half a billion. In 2015 Europe was at its most prosperous and secure ever in history. Many more millions did much smaller and heavily devastated western Europe accept and integrate in the wake of World War II during the latter half of the 1940s. That is why the more shocking must have been to Bacharevič and like-minded intellectuals and thinkers the populist, racist and xenophobic reaction to the inflow of these refugees, otherwise so much needed by Europe’s aging societies. And yet worse, this negative reaction brought about the almost concomitant rise of pro-authoritarian far right movements, parties and actual governments of this political character, while prior to 2015 such views used to be marginal. The lunatic fringe became a new norm of European and American politics. The situation is more than astounding given that the Europe of human rights, equality, individual liberties, rule of law, the freedom of speech, democracy and solidarity (fraternité) turned against these very values when it came to extending a helping hand to the huddled masses at the EU’s borders. The old Christian Gospel’s message of ‘love thy neighbor’ was thrown overboard, although the xenophobic and authoritarian movements brandish the cross of Christianity as their most revered symbol of the self-declared white and ‘normal’ (heterosexual) race. The poignancy of this betrayal of Europe by itself is even acuter from the perspective of authoritarian Belarus. During the two initial post-Soviet decades, the hope was that with time Belarus would become more like ‘democratic Europe.’ However, now it seems to be the other way round, many EU member states have become more like Belarus and Putin’s Russia, while Trump’s United States follow the same path. The rulers of unashamedly totalitarian (in spite of its current colorful hi-tech camouflage) communist China must feel vindicated that one way or another the west follows Beijing’s ideological path of ‘harmonious society.’

Literature is not politics, but behind the plot lines of his latest novel, I sense Bacharevič’s despair that the brunt of upholding these values, which he holds dear seem to be resting now on his fiction. The bulky ‘shoulders’ of beautifully published Sabaki Eŭropy, becoming the infectious readability of this novel’s stories, are sure to withstand this responsibility for a time, without losing the reader to the boredom of didacticism. The leading immersive principle of belles lettres is never to afford the reader a space for thinking about something else than the novel’s world divined into being by the writer’s magic wand. Bacharevič excels at this command.

From the structural point of view, one is tempted to say that Sabaki Eŭropy is a collection of six loosely connected stories. But this is a simplistic interpretation. From the temporal perspective, these stories are a history of the future foretold of Belarus and Europe. Hence, the novel is de facto composed from stories within stories, like the Polish-Lithuanian aristocrat, Jan Potocki’s, French-language pan-European novel, titled The Manuscript Found in Saragossa. During the Enlightenment, philosophes and writers, like Potocki, offered a modicum of freedom for imagination, between the covers of their often banned, burned, and yet ceaselessly smuggled books in the Europe of absolutist monarchies. In Sabaki Eŭropy, Bacharevič smuggles back the very freedoms and ideas that make present-day central Europe’s paternalistic, nationalist and homophobic authoritarian leaders shudder. He smuggles them across the militarized frontier Wall of the Russian Reich of the mid-21st century, which had conquered half of China, India and Pakistan. In Story 6 ‘Ślied’ (The Trace), as once in the Third Reich, guarding German shepherd dogs make sure that an unwanted traveler would not cross the border. This future totalitarian unfreedom is opposed to the individual freedom of a beautiful French woman-savant to make love to her sprightly sighthound, if she chooses so. She published an illustrated diary of her amorous adventures with a canine lover, written in her own constructed language, which no one has been able to crack.

This rare publication constitutes a counterpoint of the detective-like Story 1 ‘My liohkija, jak papiera’ (We are as Light as Paper), which takes place in today’s Miensk. A middle-aged school teacher, who thinks he is still young, befriends a student of his, who astounds him with his facility at developing a constructed language, or kanlanh. This jargon word sounds almost like slangy kanclah (‘concentration camp’). In the end, the supposedly opposed poles of freedom and unfreedom may be the same. Especially, if the worship of a language (for instance, Belarusian) or ideology (for example, the Belarusian nation) replaces real-life relations with other people. The story’s team of two develop a language named Balbut (‘Blah-blah’), but soon the student becomes the master of this game. The inevitable conflict comes to the fore, when an accidentally encountered girl joins them. Behind his teacher’s back, the student comes up with a new constructed language to woo her. The teacher is unable to forgive this betrayal, as he wrongly thought the girl had fallen for him. In a police station this teacher is convinced he killed the student, but there is no proof of the crime. At home he unravels, and his constant fear of his never appearing wife, turns out to be a forgotten paper cut-out figure from his childhood. The expectations of machismo were too steep for the teacher to scale, he never progressed beyond an imaginary paper love. Is the fact of not having been imprisoned and having your own language a real freedom?

The grammar and dictionary of Balbut is appended to the volume’s end. Documents and sentences in this constructed language appear in the novel’s various corners, including the poem that intervenes between the two initial stories, and across most of the text of Story 5 ‘Kapsuła času’ (The Time Capsule). English and German sentences pop up at times, also phonetically noted in Cyrillic, alongside Belarusian and Russian counterparts jotted down in the Belarusian Latin alphabet. Unlike continental Europe’s academies of languages and literatures, Bacharevič disagrees that languages’ orthographies must be ‘periodically reformed’ (updated). When he quotes a Russian text from before 1917, he uses all the letters and conventions, which subsequently the Bolsheviks banned. As a result, they falsified classical novels by Tolstoy or Dostoevsky, when these were republished in the Soviet Union in ‘modernized and revolutionary’ Russian.

Story 2 ‘Husi, liudzi, liebiedzi’ (Geese, People, Swans) is a fairy tale of the future, taking place in 2049, when Belarus had already disappeared in the loving embrace the Russian Reich. It was annexed out of existence in the wake of the 2030s war against Europe, resoundingly won by octogenarian Putin’s Russia. When Bacharevič wrote his novel, it was just another invention, though the fear of such a development became palpable after the Kremlin’s 2014 annexation of Crimea. In 2019 the Russian mass media began openly discussing the ‘2024 problem.’ According to the Russian Constitution, following the second consecutive term in office, President Putin would need to step down, which is not an option. There is no taste for changing the Russian constitution, either. Hence, contributing to many Belarusians’ existential fear, the ‘obvious solution,’ according to Russian pundits, would be completing the ‘unification’ of Belarus with the Russian Federation. This would allow for counting Putin’s terms yet again from scratch, because he would become President of the brand new polity, namely, the Union State of Russia-Belarus, or this novel’s Russian Reich.

Story 2’s plot-line is loosely based on the Swedish writer Selma Lagerlöf’s children novel, The Wonderful Adventures of Nils. It takes place in the border zone village of Bielyia Rosy 13. The name refers to the Soviet Belarusian feature film Belye rosy (‘White Dew’), which Bacharevič interprets as Soviet propaganda’s attempt for the underhand falsification of history and spearheading Russification in Belarus. An old shock worker tells his grandchildren the spurious story that the shared name of their village and Belarus comes from their country’s name ‘White Ros,’ or Ros for Rossiia (‘Russia’). In reality it was the medieval polity of Rus’, whose lands mostly overlaps with today’s Belarus and Ukraine. In Story 2, the village’s inhabitants speak ‘funnily’ (that is, in Belarusian). Civil servants and officers are sent from Moscow to draft young males to the imperial army for never-ending wars, which the Reich wages across eastern and southern Asia. The imperial army teaches them proper Russian, and most never return home. Maŭčun (‘Silent Boy’) wants to know what is in the forbidden west, beyond the scary frontier forest where people disappear without a trace when picking berries or mushrooms to close to the secret border installations. In the forest, he chances upon a beautiful lady Stefka, who is a western agent of all the western freedoms, now forbidden in the Reich. She befriends the boy, but in the end it turns out that Stefka does not really care about Maŭčun. He is a mere pawn in another game of security agencies. The insomniac, always – day or night – clean-shaven Muscovian officer, who then lodges in the boy’s family hut, observes and follows Maŭčun. When he discovers Stefka, in a murderous confrontation both turn out to be military robots. Frightened Maŭčun, embraces his beloved goose, and they fly away from this horror. To the liberation afforded by the blue sky. But a border guard spots them. The boy is shot down, and falls down to earth, holding for his dear to a goose feather. The goose is allowed to continue in her flight, guards are interested only in humans.

This goose feather of lost Belarusianness links this story with the final Story 6. But for the time being, let us turn to Story 3 ‘Nieandertalski lies’ (The Neanderthal Forest). Old Bianihna (perhaps an anagram of bahinia ‘goddess’) is a babka, or a female witch-healer. Another strong woman of Bacharevič’s fiction. Her hut is located on the border between the two forests, the Anderthal one, where we all live, and the Neanderthal Forest of hereafter. She heals by taking evil that he finds in sick people from the former forest to the latter. Ailing women, men and children from all around Belarus flock to her for help. Bianihna married three times, and lost her successive husbands to accidents and alcoholism. A usual post-Soviet tale of everyday grief. One day emissaries of the secretive leader of new Kryvia (an early 20th-century name for Belarus – derived from the name of a medieval ethnic group – that never gained much popularity) arrive at her hut and propose a marriage on his behalf. Bianihna, who could be Maksim’s granny wavers. The emissaries kidnap her and transport in a car first to Miensk, and then to Lithuania. From the latter country a private jet takes them to the island of Kryvia, or a Mediterranean toxic waste dump, between Italy and Greece, which Maksim bought at a bargain price. The independent and exclusively Belarusian-speaking Belarus of Belarusian nationalists’ dreams is an authoritarian pseudo-monarchy. The few inhabitants lured to this project suffer a serious carcinogenic skin disease. Bianihna, as a symbol and latter-day practitioner of Belarus’s indigenous pre-Christian powers, was kidnapped to cure them of this unseemly malady. And she does, only to be turned into the pillar of Kryvia’s economy. She slaves as a healer for rich patients from all over the world, until Kryvia is taken over by Mediterranean refugees arriving in boats. Bianihna is secreted to Germany, where she continues to be abused in the same role in the scenic valley of the Neander River, or in the Neanderthal, until she dies and moves to the non-national Neanderthal Forest. A poignant #MeToo parable on trafficking vulnerable women in today’s Europe of human rights.

Story 4 ‘Tryccać gradusaŭ u cieni’ (Thirty Degrees in Shadow) is simultaneously a burlesque and an ode to the ubiquitous pakiet, or ‘plastic bag.’ Once it used to be a sign of the higher status of a buyer with an envied access to western consumer goods in freshly post-Soviet countries. The narrator’s mum, who left by plane for Berlin, on saying a good-bye in the Miensk Airport, left her son with another unenviable task – to deliver a plastic bag with its mysterious content to a person in a peripheral district of Miensk. This phantasmagoric and repeatedly unsuccessful voyage through the closely observed sun-scorched cityscape and the metro underground of the present-day Belarusian capital brings to the narrator’s mind musings about Nils shot down and an oppositionist who bought himself a sea island. Story 5 ‘Kapsuła času’ (The Time Capsule) is also placed in the present but brandishes with a temporal twist. A frustrated teacher striving to get their students interested in something, develops the idea of a time capsule, to which all his class are expected to contribute. Among these contributions is a letter in Balbut, cited verbatim. This deus ex machina device links the present with the future.

Four decades later, in the Berlin of 2050, a dead poet of an unknown language is discovered in a cheap hotel. Was it Bluerusian, Greenrusian, Yellowrusian, or Whiterusian in which he composed poetry? The dilemma underpins the tour de force of Story 6 ‘Ślied’ (The Trace). The only trace to be followed is the goose feather tightly clasped in the poet’s hand. Was the poet this shot-down Maŭčun-Nils of Story 2? Did the boy manage to evade Reich border guards and reach the west? Inspector Terezius Skima’s job is to establish document-less deceased persons’ names and other personal details. In Europe they still care about such details, individual freedom is protected, democracy survived the 2030s war with the Russian Reich. The Czech Republic and Slovakia are still EU members, but presciently Bacharevič is silent about the fate of Poland. Perhaps this country was annexed for creating a strategic land bridge between the Kremlin’s Kaliningrad enclave and the New Russia of Ukraine? The unisex fashion of the future times is dresses and skirts. The inspector’s mythological name of gender-shifting Tiresias symbolizes the freedom to love and having sex with whomever one wants, provided that the other person consents. Not all is that easy, because in Berlin’s Turkish district male shopkeepers in respectfully long dresses disapprove of Skima’s short skirt and plunging neckline that shows his chest hair. However, the inspector’s sartorial taste is appreciates by his female acquaintances, who tend to borrow Skima’s clothes.

It is a Europe of social media and electronic communication, where the environment-unfriendly employment of paper for printing is a thing of the distant past. Only few weirdos trade in old dusty clumps of moldy paper, which are supposedly to be known by the name of ‘books.’ Some of these harmless eccentrics even produce new books of poetry. The search for any clues about the dead poet leads Skima to the underground, unhygienic and hard to fathom netherworld of surviving bookshops. He travels hectically taking Eurocity trains to Hamburg, Paris, Prague and Bratislava, or Bacharevič’s beloved central European cities of culture and literature. The dead poet wrote in Belarusian, which was unlike the Reich’s Russian, so the market was limited. A bookseller interested in publishing his poems encouraged him to translate these into another language. The poet followed this advice, and translated some into Balbut, which was not of much help, either. However, this clue allows Skima to direct his search to Minsk (now not Miensk any longer), or the Reich’s western capital. The neoimperial Russia of one truth, one leader, one language and homophobia is not to the inspector’s liking. His is the Europe of Gulliver and Nils, of works written by Dadaists, Nabokov, Stein, Joyce, Woolf, Kafka, (the imaginary) von Schtukar, Sylvia Beach, Chadasievič and Mandelstam. Should such Europe be no more, it is necessary for Skima and Bacharevič to (re)invent this continent of culture, liberty and solidarity, so as not to go mad and fall for the poisonous lure of the ‘hetero-orthodoxy’ of the Russian Reich of the Third Rome, the racial purity of the Third Reich, or for the Middle Reich of China’s wool-over-the-eyes, composed from colorful hi-tech nothings.

Unfortunately, western publishing houses and reviewers have not taken a note of this Belarusian-cum-European 1Q84. Life is too short to wait for decades on end, before a writer’s novel makes it in the ‘big world’ of the west. Whatever Bacharevič may think of the Russian language, its almost 200 million users constitute an opportunity that should not be missed. He translated his novel into Russian, and in 2019 Собаки Европы Sobaki Evropy was released in Moscow. This translation was already added to the short list of Russia’s prestigious Big Book (Большая Книга Bolshaia Kniga) literary award. I keep fingers crossed that Bacharevič may win this becoming accolade from the country whose government and politics he never tires to criticize. On the other hand, he appreciates Russian literature of the highest caliber, because literature has no nationality beyond beauty and the thrill of the unexpected.

In this manner, Bacharevič steps in the shoes of his famous compatriots. Early in his career, Vasil Bykaŭ heard a low opinion about his novel translated into Russian. He read this translation and was appalled how cavalierly the translator misinterpreted intended meanings and subtle turns of phrase, perhaps, believing the old chestnut that Belarusian is just a dialect of Russian. That whatever appeared similar should be Russianized without the pain of referring to a dictionary, while ‘harder parts’ could be freely adapted. In the postwar Soviet Union, fiction and poetry composed in the republics’ national languages had to be first published in Russian translations, before the originals could appear. Little attention was lavished on such translations beyond paying lip service to the interethnic friendship of the Soviet peoples. Socialist ‘literary’ production mattered more than any literary considerations. Unlike in the case of Russian-language works carefully translated into the western world’s leading languages for the sake of promoting communism around the globe.

Bykaŭ would not have it. This giant of 20th-century Belarusian and Soviet literature harnessed himself to translating his own voluminous writings into Russian, so their beauty would not be lost in the run of the Soviet literary mill. Facing such odds, Sviatlana Alieksijevič chose to write exclusively in Russian. Her compassionate portrayals of the 20th-century tragedies of the Soviet people retold in their own words earned her a Nobel Prize in literature. That is why, in the world, she is better known under the Russian version of her name, as Svetlana Aleksievich. Young Łukašenka hounded old Bykaŭ out from Belarus into exile in Finland, Germany and the Czech Republic. Now old Łukašenka makes his best not to notice Alieksijevič and to marginalize her. She criticizes the strongman as Bykaŭ used to. But during the recent decades the regime mellowed having noticed that the locus of power does not rest among the chattering classes but where oil is. Yet, Łukašenka did not fail to prevent however small a state subsidy to be ‘wasted’ on the eventually crowd-founded translations of Alieksijevič’s collected works into Belarusian. To add insult to injury, many of the country’s public libraries declined the free gift of her works in Belarusian, claiming that readers are not interested, that the Russian-language originals of Alieksijevič’s books are enough.

Writers are free to write in today’s Belarus if they keep to writing, and – importantly –stay away from politics. After returning from German exile in Hamburg, Bacharevič toes this tolerated middle route earmarked for independent Belarusian intellectuals who want no trouble with the authorities. With time, translations into other languages will follow the Russian translations of Bacharevič’s brilliant novels, as in the case of Bykaŭ. Keeping the nerve is a must until this moment, which seems to lie in not too distant a future, somewhen in the mid-2020s. Or a decade before the prophesized 2030s war between the Russian Reich and Europe, which I hope will never happen. In 2030 the writer will turn only 55. Let him enjoy the hard-earned fame for longer. He well deserves it for all the literary and artistic pleasures, which Bacharevič conjures with each of his books. Long live writers who write!

October 2019