Tomasz Kamusella: Why Not Silesian in Silesia?

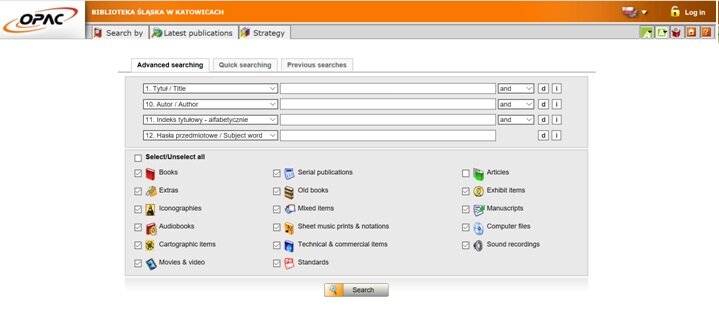

The Silesian Library (Biblioteka Śląska in Polish) in Katowice is one of Poland’s largest libraries and the largest one in the historical region of Upper Silesia. This Library’s website (http://www.bs.katowice.pl/en/about_library) and online catalog (https://opacwww.bs.katowice.pl/cgi-bin/wspd_cgi.sh/wo2_search.p?R=1&IDBibl=3&ID1=FIJFQNDERPGJOLNJLRNM&ln=EN) are available in Polish and English. Obviously, the former is Poland’s official and national language, while English is the lingua franca of today’s Europe and scholarship.

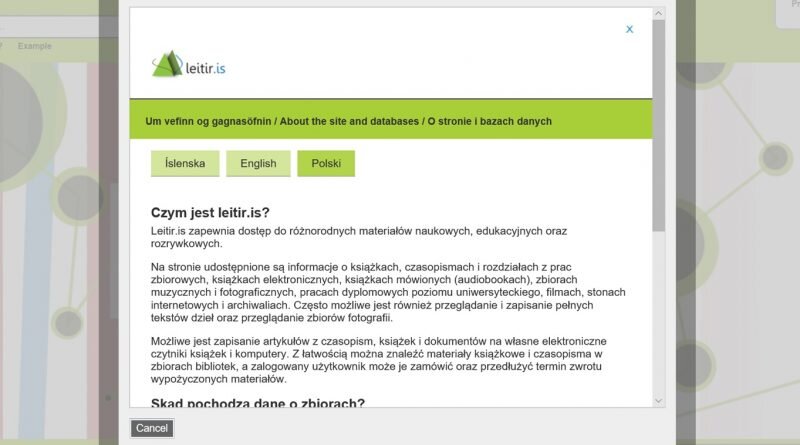

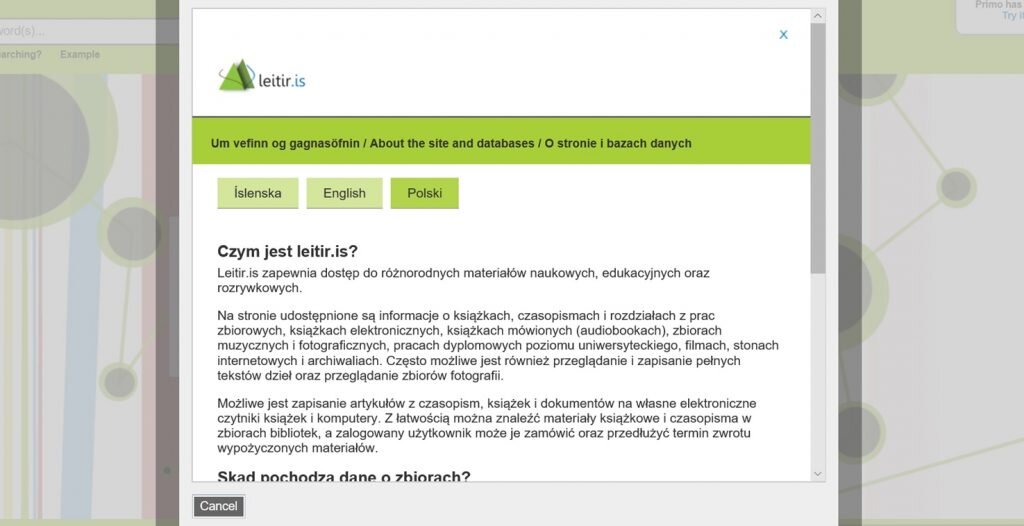

Recently, while idling on the web, I stumbled across leitir.is, which is Iceland’s largest metacatolog (https://leitir.is/primo_library/libweb/action/search.do?vid=ICE&dscnt=0&dstmp=1549889155745&vid=ICE&backFromPreferences=true). Nothing special, as such metacatalogs abound across the world. It offers the online search interface and website information in Icelandic and English, another widespread standard of pairing the national (state) language with the contemporary world’s international lingua franca. But I was for a surprise, as this interface and information are also provided in Polish.

Why Polish? Well, in the wake of Poland’s 2004 accession into the European Union (EU), thousands of Poles went to Iceland in search of gainful employment and a decent standard of living. Iceland is not an EU member state, but it is tightly associated with this Union through the EU’s European Economic Area (EEA). In 2017, official statistics registered almost 17,000 Poles in Iceland, meaning around 4 percent of the country’s population of 357,000. Unofficial sources speak even of 40,000 Polish citizens in today’s Iceland (https://www.bankier.pl/wiadomosc/Inwazja-Polakow-na-Islandie-Tam-mieszkam-7604745.html), who thus may amount to over a tenth of Iceland’s inhabitants. These Poles are this island state’s second largest ethnic group after the Icelanders. In 2012 the Polish Embassy in Reykjavik proudly informed that the first-ever Polish language book was published in Iceland (https://reykjavik.msz.gov.pl/pl/aktualnosci/0_islandia_jak_z_bajki__pierwsza_ksiazka_wydana_w_islandii_w_jezyku_polskim?printMode=true).

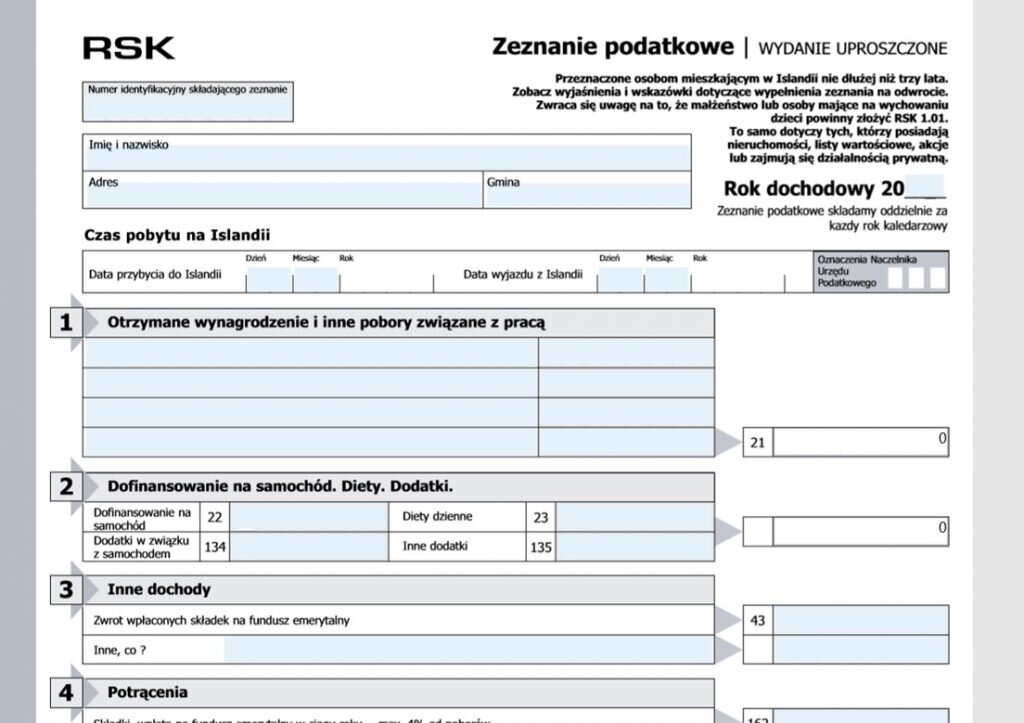

Quite pragmatically, apart from making official services available in Icelandic and English, the Icelandic administration also provides them in Polish, for instance, tax return forms (https://www.rsk.is/media/rsk01/rsk_0113.pl.pdf). Obviously, this pragmatic approach extends to the access to information, including Iceland’s network of libraries.

The Silesians, numbering close to a million, are Poland’s second largest ethnic group after the Poles. This is almost 3 percent of the country’s population of 35 million, or 2.5 times more than all the inhabitants in Iceland. The Silesians’ language of Silesian (ślōnskŏ gŏdka) is the second most spoken language in present-day Poland after Polish. At least half a million people employ Silesian in everyday life. The vast majority of these Silesian-speakers reside in their native region of (Upper) Silesia. In the region’s population of 5.5 million, Silesian-speakers amount to 9 percent, and all the Silesians to 18 percent. More than ten Silesian-language books are published every year, while the use of Silesian online is quite widespread.

These numbers show clearly that not only should the catalog of the Silesian Library be available in the Silesian language, but comparatively speaking many more official services than those which are provided in Polish across Iceland. Why not to adopt the practical Icelandic approach to languages? Especially nowadays after Zbigniew Kadłubek became Director of the Silesian Library in 2018. He is one of the best living writers in Silesian, whose 2008 essayistic novel Briyfy s Rziyma (Letters from Rome) trailblazed the path for the blooming of Silesian-language literature during the last decade.

Ethnolinguistic nationalism of a highly exclusivist character has been on the rapid rise in Poland after the currently ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party assumed power in 2015. The fear is that they may prevent any meaningful moves to make official services available in Silesian in the region of Upper Silesia. Neither the sitting PiS government, nor the previous ones of more liberal leanings have decided to recognize Silesian as a language. But the Silesian Library is an autonomous institution, and no law prevents it from making its catalog interface available in Silesian, as no regulations require to provide this interface in English either. Director Kadłubek can make such a pragmatic decision, whom some would see as brave and only fitting, given that the vast majority of Silesian-language books and periodicals are deposited in the Silesian Library only.

February 2019

University of St Andrews