Tomasz Kamusella: North Macedonia – A Surprise (Ślōnske ôpisaniy świata #1)

Tomasz Kamusella

University of St Andrews

After twenty years, in March 2019, I revisited Macedonia, whose name had just been altered to ‘North Macedonia,’ so that Greece would stop blocking the country’s desired accession to NATO and the European Union. I did not know what to expect.

Changing the state’s name: From Macedonia to North Macedonia, January 2019 (Source: Сакам Да Кажам, https://sdk.mk/index.php/makedonija/politsijata-gi-chuva-tablite-so-severna-makedonija-24-chasa-na-den-za-da-ne-gi-ischkrtaat-kako-avtopatot-prijatelstvo/)

Changing the state’s name: From Macedonia to North Macedonia, January 2019 (Source: Сакам Да Кажам, https://sdk.mk/index.php/makedonija/politsijata-gi-chuva-tablite-so-severna-makedonija-24-chasa-na-den-za-da-ne-gi-ischkrtaat-kako-avtopatot-prijatelstvo/)

Twenty Years Earlier: The Deepening Ethnic Cleavages

In 1999, Macedonia was the sole post-Yugoslav polity, which had escaped the ravages of a military conflict. Western commentators lauded it as a sole bright spot in the (western) Balkans. Few paid attention to the murky Serbian overtures to Athens for attacking and partitioning Macedonia between Greece and Serbia. To my knowledge, no monograph has been devoted to this – fortunately – unrealized plan for opening a southern front in the course of the wars of Yugoslav succession. I just chanced upon some journalistic mentions of such Serbian-Greek talks in a couple of Greek-language articles on Greek paramilitaries in the Serbian forces fighting against Muslims (Bosniaks and Albanians) and Catholics (Croatians).

In the summer of 1999 I attended a postgraduate summer school in Skopje (now also officially known under its Albanian moniker, as Shkup) organized by Suzana Milevska with the support of the Open Society Institute. We were accommodated in the then quite dilapidated Hotel Continental, which we dubbed ‘Hotel Conti’ on the account of the non-functioning letters ‘ental’ in the huge neon on the establishment’s top. Hotel guests smoked with abandon in the breakfast hall, adorned with the sign Ne puši (‘Do not smoke’). Smoking was then rife, including taxis and city buses. The summer school’s participants had a great time, exploring the Macedonian capital, and enjoying weekend trips to Lake Ohrid (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lake_Ohrid), Matka Canyon (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matka_Canyon) and the Galičnik Wedding Festival (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galičnik_Wedding_Festival) in the Bistra mountain range on the border with Albania. The school’s topic was ‘The Image of the Other.’ The participants and tutors were expected to discuss how to question, transcend, and even transgress and subvert the obtaining social and political norms in Europe. Not surprisingly, given our youth, we liked best Elizabeta Seleva’s postmodern take on ‘Dr Phallus as a Figure of Knowledge.’ She enlightened us that Orthodox monks tend to be the best seducers. We were expected to write articles on our own research, as inspired by this unique Macedonian sojourn. These pieces were promptly published in an edited volume (Suzana Milevska, ed. 2000. The Image of the Other: The Perception and the Representation of the Others. Skopje: Foundation Open Society Institute Macedonia).

Ottoman Skopje nowadays (Source: Wikipedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Поглед_кон_Сули_Ан_и_Старата_скопска_чаршија.JPG)

Ottoman Skopje nowadays (Source: Wikipedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Поглед_кон_Сули_Ан_и_Старата_скопска_чаршија.JPG)

My article was not included in the collection. What first struck me in Skopje was the survival of the Ottoman architecture, be it ubiquitous mosques, hamams (baths), or the Čaršija / Çarşısı, that is, the Old Bazaar (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_Bazaar,_Skopje), which was the largest in the Ottoman Balkans. In Skopje the sound of tolling church bells intertwined liberally with the ezan, or the muezzin’s call for prayer. But on the other hand, it was the time when the premeditated Serbian (Orthodox) destruction of mosques and any material traces of Muslim (that is, Ottoman) culture in Bosnia and Kosovo regularly made it to the front pages of international newspapers. The 1992 burning of Bosnia’s National Library in Sarajevo (https://www.dw.com/en/burned-library-symbolizes-multiethnic-sarajevo/a-16192965), the 1993 blowing-up of the Old Bridge in the Bosnian town of Mostar (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stari_Most#Destruction), and the widespread destruction of mosques and tekkes (sufi lodges) in Kosovo in 1998-1999 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Destruction_of_Albanian_heritage_in_Kosovo#Kosovo_Conflict_(1998-1999) ) were symbolic of what the ‘norm’ used to be then in the Balkans, when Muslim or Ottoman heritage was considered.

In 1992, during the siege of Sarajevo, Vedran Smailović plays the viola in the destroyed National Library of Bosnia (Source: Wikipedia, https://bs.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nacionalna_i_univerzitetska_biblioteka_Bosne_i_Hercegovine#/media/File:Evstafiev-bosnia-cello.jpg)

In 1992, during the siege of Sarajevo, Vedran Smailović plays the viola in the destroyed National Library of Bosnia (Source: Wikipedia, https://bs.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nacionalna_i_univerzitetska_biblioteka_Bosne_i_Hercegovine#/media/File:Evstafiev-bosnia-cello.jpg)

Macedonia was different. Macedonia was the Other. It was a lucky exception. This country successfully transgressed against the aforementioned ‘norm.’ Maybe the destructive 1963 earthquake, which had levelled Skopje was a warning enough that it is better to build, preserve and coexist than to destroy or kill, however enticing an ideology may appear. The summer school took place during the very last stage of the NATO bombing campaign against New Yugoslavia (namely, Serbia-Montenegro), as a reprisal for Belgrade’s wholesale expulsion of 0.85 million Albanians, Muslims and Roma from Kosovo in 1998-1999. Almost 400,000 of these expellees found safe haven in neighboring Macedonia. Although they accounted for a third of the country’s population, almost no refugee camps sprang up, most of the expellees supplied with lodgings by family or Albanian ethnic kin. When we were getting ready to leave Skopje, NATO seized control over Kosovo from Serbia, and the refugees began streaming back home. The expense of providing aid to the expellees was enormous from Macedonia’s perspective, and cost the economy a steep 10 percent dip in the country’s GDP in 2000.

Skopje destroyed by the 1963 earthquake (Source: Wikipedia, https://mk.wikipedia.org/wiki/Скопски_земјотрес_1963#/media/File:Plostad_Sloboda_po_zemjotresot_vo_Skopje.jpg)

Skopje destroyed by the 1963 earthquake (Source: Wikipedia, https://mk.wikipedia.org/wiki/Скопски_земјотрес_1963#/media/File:Plostad_Sloboda_po_zemjotresot_vo_Skopje.jpg)

We observed slow-moving columns of refugees on television or read about them in newspapers, but the organizers made sure – perhaps for security reasons – we would not see the rapidly unfolding events with our own eyes. The topic did not pop up in our discussions during lectures or seminars, either. However, these events starkly polarized Macedonian society, making ethnic cleavages more prominent than in the past. The Macedonian government stepped up its efforts to build a homogenous Slavophone and Orthodox nation-state. The public space accorded to Muslim Albanians, Turks and Roma shrank rapidly, though they account for a full one third of the country’s population. All were required to speak and learn through the medium of Macedonian. The Albanian-language educational system was then increasingly neglected and limited. Obviously, no Albanian, Turk or Roma was included in the summer school’s staff. When I voiced an off-cuff idea that maybe it would be good for Slavophone Macedonians to reciprocate with learning some Albanian, I was gently scoffed at. Only a teaching assistant confided to me over lunch that her husband was Albanian, though they spoke Macedonian at home. However, in order to give their daughter equal access to both parts of their family, they sent her to an Albanian-medium kindergarten. For this ‘national misdemeanor’ alone, the teaching assistant’s Macedonian friends immediately began avoiding her.

Kosovo refugees returning home in June 1999 (Source: NATO Review, https://www.nato.int/pictures/review/9903/b9903-20.jpg)

Kosovo refugees returning home in June 1999 (Source: NATO Review, https://www.nato.int/pictures/review/9903/b9903-20.jpg)

As requested by the organizers, I devoted my article to what I saw and experienced in Macedonia. What struck me most was the ethnic division of this city. The city center and Gazi Baba were unquestionably Macedonian, Albanians constituted the majority of the inhabitants in the municipality of Čair, while Roma in Šuto Orizari. In this arrangement, the Čaršija constituted Skopj’s liminal space of commerce, where all – irrespective of ethnicity – brushed sides during the day, but left the bazaar empty at night. During the summer school, the unspoken rule was to turn a blind eye to this reality. I dared to cross this thin red line and was exiled from the edited volume. But truly speaking, with the privilege of hindsight, there was nothing strange or sinister in this ethnic division itself, just a continuation of the Ottoman tradition, in which members of different millets (or autonomous ethnoreligious groups) used to live in separate mahallas (city quarters): Orthodox Christians in one, Muslims in another, while Catholics and Roma (predominantly confessing Islam) yet in different mahallas altogether.

The market entrance gates in Šuto Orizari, adorned with the Roma national symbol of chakra (wheel with spokes) (Source: Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Šuto_Orizari_Municipality#/media/File:Shuto_Orizari_-_P1090581.JPG)

The market entrance gates in Šuto Orizari, adorned with the Roma national symbol of chakra (wheel with spokes) (Source: Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Šuto_Orizari_Municipality#/media/File:Shuto_Orizari_-_P1090581.JPG)

What motivated the summer school’s organizers to take care not to puncture the balloon of silence around the subject was, maybe, the then rife political aspiration of erasing these divisions by turning everyone in a true ‘Macedonian,’ meaning ‘Slavic-speaking Orthodox Christian.’ In this drive at implementing the Central European model of ethnolinguistically and ethnoreligiously homogenous nation-state in Macedonia, somehow the fact was lost on the country’s political and intellectual elite that exactly the same program had already led to numerous acts of ethnic cleansing and genocide during the post-Yugoslav wars, including the expulsion of Albanians, Turks and Roma from Kosovo. That forcing Macedonia’s Albanian-, Romani- and Turkish-speakers to give up on their culture and religion may backfire.

Monument of the 2001 Defenders of Macedonia, unveiled in 2011 in the center of Skopje (Source: Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2001_insurgency_in_the_Republic_of_Macedonia#/media/File:Monument_of_the_Defenders_of_Macedonia.JPG)

Monument of the 2001 Defenders of Macedonia, unveiled in 2011 in the center of Skopje (Source: Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2001_insurgency_in_the_Republic_of_Macedonia#/media/File:Monument_of_the_Defenders_of_Macedonia.JPG)

Monument to the 2001 UÇK (National Liberation Army) Albanian fighters, unveiled in Čair in 2016 (Source: https://gymlive.org/grupkarshijaka/photo/1443571572102155692_4546263229)

Monument to the 2001 UÇK (National Liberation Army) Albanian fighters, unveiled in Čair in 2016 (Source: https://gymlive.org/grupkarshijaka/photo/1443571572102155692_4546263229)

Reconciliation is possible: Macedonia’s Slavophone Macedonians and Albanians united (Source: http://www.macedoniantruth.org/forum/showthread.php?p=164024)

Reconciliation is possible: Macedonia’s Slavophone Macedonians and Albanians united (Source: http://www.macedoniantruth.org/forum/showthread.php?p=164024)

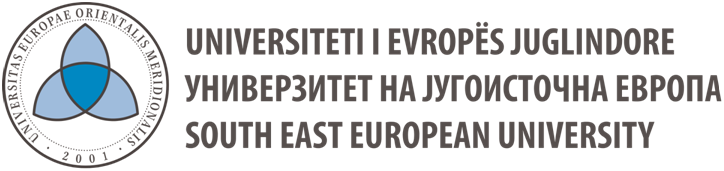

And it did soon enough. In 2001 the civil war fought between Albanian partisans and the Macedonian army cost over one thousand people their lives, whilst the fighting displaced 140,000 more. The tortuous postwar decade of bickering about the implementation of the 2001 Ohrid Peace Agreement (http://www.ucd.ie/ibis/filestore/Ohrid%20Framework%20Agreement.pdf) could have been avoided, had the Macedonian administration learned a lesson or two from the earlier post-Yugoslav conflicts. But it appears that history is no teacher of anything. Compromising on the national ideal of ethnolinguistic homogeneity was a slow process. The Ohrid Agreement provided for non-discrimination and equitable representation of all the country’s ethnic and linguistic groups, decentralization, and the use of minority languages (especially in education) across administrative units with more than one fifth of the inhabitants belonging to a minority ethnic group. The first tangible success came with the 2004 recognition of the Albanian-medium Tetovo University, which had been founded a decade earlier (in 1994). Because this recognition took so long, in 2001 the Albanian community established South East European University in Tetovo as a private non-profit Albanian-language institution.

Unity in diversity: The official logo and signage of South East European University in Latin, Albanian, Macedonian and English (Sources: Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_East_European_University#/media/File:South_East_European_University_logo.svg)

Unity in diversity: The official logo and signage of South East European University in Latin, Albanian, Macedonian and English (Sources: Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_East_European_University#/media/File:South_East_European_University_logo.svg)

The New Opening in 2019: Toward Inclusive North Macedonia

However, a real breakthrough in the sphere of language policy came in January 2019, when Albanian was recognized as Macedonia’s second official language, alongside the country’s national and first official language of Macedonian (https://www.rferl.org/a/macedonia-s-albanian-language-bill-becomes-law/29711502.html). Not all, but the majority of Macedonian Albanians know at least some Macedonian (or mutually comprehensible Serbo-Croatian in the case of the middle-aged and older generations), unlike most Slavic-speaking Macedonians who rarely have any working command of Albanian. But there is a clear hope for a swift improvement in this regard. In mid-March 2019, at Saints Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje / Shkup, I met Aneta Dučevska, Dean of the Blaže Koneski Faculty of Philology, and her colleagues. They let me know that in October 2018 theor faculty offered a free non-compulsory course in Albanian to all students at the university. They expected 20 takers, but to everyone’s surprise about 150 students decided to enroll. This fact indicates a profound change in the thinking about Macedonian society among the young generation, who are going to shape the country’s future in the coming decades.

The direction of this change may potentially lead to an emulation of the Finnish model of genuine official bilingualism. Finland’s official bilingualism was established in the Scandinavian country in the wake of the near-genocidal civil war of 1918. Dring the three months of the conflict’s duration almost 40,000 people had lost their lives, or more than one percent out of the population of three million. Had the war continued for a full year, it could have been as many as four percent. In today’s Finland, Swedish-speakers account for about five percent of the inhabitants, but all Finnish-speakers are required to master Swedish at school. Likewise, the former need to acquire Finnish. In order to graduate from school and enter university in Finland one needs to pass tests in both languages. This strictly observed policy, not liked either by Finnish or Swedish nationalists, ensures a solid basis for integration on which the state’s stability has been built. Finland is the national polity of the nation of bilingual Finlanders (not Finns, as is commonly – but mistakenly – believed). Why couldn’t then Macedonia’s Albanians and Macedonians become a multilingual nation of Macedoners, the name melding the Albanian-language designation for ‘Macedonians,’ namely, Maqedonët, with the Macedonian one of Македонци Makedonci. The measure of success in the case of the Finnish policy of inclusive national bilingualism is the fact that among all the countries attacked by the Soviet Union during World War II, the Finlanders alone managed to stop the Red Army in its tracks and preserve their country’s independence. Historically speaking, between 1917 and 1956, eastern Scandinavia was as unstable as today’s western Balkans. But apparently decisions may be taken to break the vicious circle of discrimination, uprisings and reprisals, as generated by sticking unyieldingly to the principles of ethnolinguistic nationalism.

Not surprisingly, the recent breakthroughs in Macedonia were possible, thanks to the unseating of the heritage Macedonian national(ist) party VMRO (Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization) from power. The current ruling coalition, which formed a cabinet in 2017, is led by the Social Democratic Union of Macedonia (SDSM), but with the participation of Albanians (BDI, Democratic Union for Integration), Roma (PCERM, Party for the Full Emancipation of the Roma of Macedonia) and Turks (PDT, Party of the Movement of Turks). A similar process took place in neighboring Greece, when in the wake of the 2008 economic crisis that hit the country hardest in the European Union, SYRIZA (Coalition of the Radical Left) repeatedly defeated the heritage Greek national(ist) parties PASOK (Panhellenic Socialist Movement) and ND (New Democracy) in the parliamentary elections of 2009 and 2014. However, it took long to partially unwed the country’s statehood and politics from ethnolinguistic nationalism and their ideological dependence on the autocephalous Orthodox Church of Greece. The Macedonian Orthodox Church, which self-declared its autocephalous status in 1967, never gained a comparable influence in Macedonia, because first, the League of Communists of Yugoslavia would not have tolerated such a breach in their monopoly of power, while second, to this day, the Ecumenical Patriarch has not recognized this Church’s autocephaly yet.

On 12 June 2018 the Greek foreign minister and its Macedonian counterpart signed a momentous agreement (http://s.kathimerini.gr/resources/article-files/symfwnia-aggliko-keimeno.pdf#Question) in the tiny village of Psaredes, on a promontory in Lake Prespa, which is the Greek locality placed closest to the point where the Greek, Macedonian and Albanian borders meet in this lake (https://www.google.co.uk/maps/place/Psarades+530+77,+Greece/@40.8293561,20.891079,11z/data=!4m5!3m4!1s0x1350b470e73ebde9:0x41e5e44b951dcb29!8m2!3d40.8297848!4d21.0317746). After half a year of heated discussions and angry protests staged by nationalists in both countries, the disputed referendum on the new name held in Macedonia, and despite Russia’s rife meddling, Skopje / Shkup and Athens successfully ratified this document in January 2019. The Prespa Agreement – as it is popularly known – came into force on 12 February 2018. In Article 1, Skopje / Shkup agreed to the change in the country’s official name to North Macedonia, which at long last ended Athens’s obstinate non-recognition of the country’s previous name. While previously the international community had settled for the neutral bureaucratic acronym FYROM (Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia), in Greece, post-Yugoslav Macedonia had been referred to with the somewhat derogatory label ‘Republic of Skopje’ (Δημοκρατία των Σκοπίων Dimokratías ton Skopíon) (http://www.thebest.gr/news/index/viewStory/190823). In return to this concession, Athens agreed to allow the unmodified adjective ‘Macedonian’ to continue as the official designation for all the inhabitants of North Macedonia (Art 1b), and as the name of the Slavic language of Macedonian (Art 1c), which previously was often dubbed as the ‘Skopjan language’ (Σκοπιανή γλώσσα Skopianí glóssa) in Greek (https://www.thepresident.gr/2018/06/07/η-μακεδονική-διάλεκτος-και-η-γλώσσα-τω/). Finally, Article 7 gives a short shrift to Greece’s and Macedonia’s bitterly opposed Geschichtspolitiken (politics of national history and remembrance), by acknowledging that the term ‘Macedonian’ has two distinctive and (mostly) unrelated meanings. On the one hand, it refers to North Macedonia, its inhabitants, and their Slavic language; while on the other, to the ancient region of Macedonia and its ‘Hellenic’ (Greek) culture and traditions. Thanks to different alphabets, no one in North Macedonia or Greece is prone to mistake these two different meanings, since the former is Македонски Makedonski in Macedonian, while the latter Μακεδόνας Makedónas in Greek. Only in English, this ideologically all-important distinction disappears in the same term ‘Macedonian’ employed for both meanings.

The Tyranny of Language Politics

However, as recently as June 2009, during the promotion of the first postcommunist Greek-Macedonian dictionary, paramilitaries of the Greek fascist and nationalist party Golden Dawn disrupted this scholarly event with the use of violence (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5UprTeTPnp0). The very name of the village where the Prespa Agreement was signed is iconic of the use of language as a weapon of politics and warfare. Until 1927 Psarades (Ψαράδες) was known as Nivitsa (Νίβιτσα), rendered as Nivici (Нивици) in Macedonian (meaning ‘fields’ in Slavic). Between 1856 and 1914, the northward expansion of the Greek nation-state from its original core in Attica, brought within this polity’s borders numerous Slavophone and Turkic-speaking territories. In emulation of Central Europe’s then increasingly more popular ideology of ethnolinguistic nationalism, many Slavophones but especially ‘Turks’ (typically, Muslims of any language or ethnicity) were expelled from Greece, while many Greeks (usually, Orthodox Christians using Greek letters for writing their various languages) from Turkey and Bulgaria to Greece between the mid-19th and mid-20th centuries. But what remained in Greece after the ‘disappearance’ of these expellees was the national anathema of Slavic and Turkic place-names. The vast majority such place-names were Greekized (Hellenized) by fiat during the first half of the 20th century. On Greek maps of the Balkans that cover North Macedonia, even place-names north of the Greek frontier are typically Greekized (http://theconversation.com/greeces-macedonian-slavic-heritage-was-wiped-out-by-linguistic-oppression-heres-how-94675 ; http://macedonia.kroraina.com/en/mv/index.html ; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geographical_name_changes_in_Greece), while Macedonian maps of Greece take care to display Slavic or Turkic traditional names next to present-day Greek ones.

Historical Macedonia – now divided among Bulgaria, Greece and Macedonia – with the place-names in Slavic, rendered with the use of the Macedonian Cyrillic (Source: https://mk.wikipedia.org/wiki/Егејска_Македонија#/media/File:Macedonia_(region)_borders_-_mk.png)

Historical Macedonia – now divided among Bulgaria, Greece and Macedonia – with the place-names in Slavic, rendered with the use of the Macedonian Cyrillic (Source: https://mk.wikipedia.org/wiki/Егејска_Македонија#/media/File:Macedonia_(region)_borders_-_mk.png)

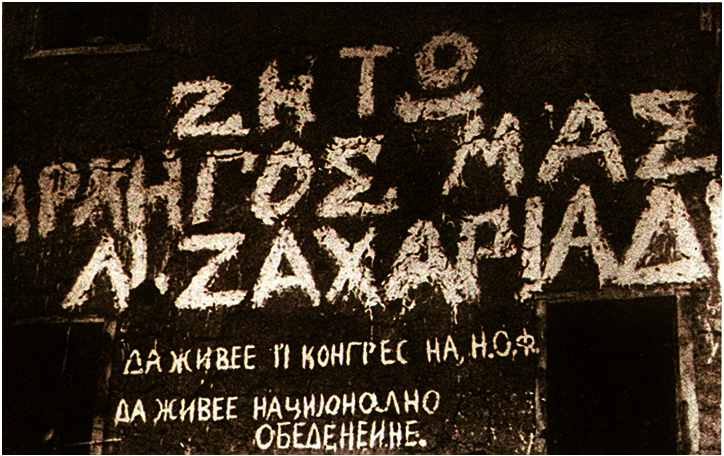

Since the interwar period, the denial of identity has remained one of the most important instruments of nation building in the Balkans. In 1938, on the French model of unitary state with no ethnolinguistic minorities recognized, republican Turkey trailblazed this path by declaring that the Indo-European-speaking Kurds are none other but ‘Mountain Turks’ (dağ Türkleri). Speaking Kurdish in public was banned. This policy changed only in 2009; now Ankara acknowledges that Kurds live in eastern Turkey and speak their own language, which is as distinctive from Turkish, as Hungarian from English. In Greece, the suppression of Albanian- and Slavic-speakers continues to this day. The former are referred to in Greek as ‘Arvanites’ (Αρβανίτες Arvanítes), and the latter as ‘Slavic-speakers’ (Σλαβόφωνοι Slavófonoi). Both groups are defined from above as ‘non-Greek-speaking Orthodox Christian Greeks,’ hence they are claimed to be radically different and separate from the Albanians (Αλβανών Alvanón) or Macedonians (Μακεδόνες Makedónes). However rarely it is necessary to publish in Greece something in Arvanatika or Slavic, invariably Greek letters are employed for this purpose. What is more, in the tradition of the Ottoman system of millets, religion trumps language, hence, Slavic-speaking Muslims are seen as Pomaks (Πομάκοι Pomákoi) in Greece, and their language, dubbed Pomakian (Πομακική Pomakikí), is posed to be separate from the aforementioned Greek Slavophones’ tongue. The only time when Greece recognized Macedonian as a language in its own right was during the Civil War (1946-1949) fought, in the wake of World War II, between communists and anti-communists. The communist Provisional Democratic Government controlled the Macedonian- and Greek-speaking north of Greece between 1947 and 1949. Without recognizing Macedonian as official and providing schools, the press, books and administration in this language, alongside Greek, communist ‘North Greece’ would have stood no chance in the bitter clash with ‘capitalist Athens.’

Bilingual Greek-Slavic slogan ‘Long live the National Liberation Front (NOF)’ (1946). NOF was a political and military organization of North Greece’s Macedonians (‘Slavs’). (Source: Wikipedia, https://mk.wikipedia.org/wiki/Народноослободителен_фронт#/media/File:Natpis_NOF.JPG)

Bilingual Greek-Slavic slogan ‘Long live the National Liberation Front (NOF)’ (1946). NOF was a political and military organization of North Greece’s Macedonians (‘Slavs’). (Source: Wikipedia, https://mk.wikipedia.org/wiki/Народноослободителен_фронт#/media/File:Natpis_NOF.JPG)

Communist North Greece’s Macedonian-language newspaper Nepokoren (The Defiant, 1947-1949) (Source: Makedonska Bibliteka http://macedonian.atspace.com/knigi/nepokoren.htm)

Communist North Greece’s Macedonian-language newspaper Nepokoren (The Defiant, 1947-1949) (Source: Makedonska Bibliteka http://macedonian.atspace.com/knigi/nepokoren.htm)

The Prespa Agreement was to do away with this ideological tyranny of the hot puff of air, which language is. But in mid-March 2019, the as yet unresolved denial of the Macedonian linguistic identity in Greece hit press headlines across Macedonia. The question being ‘if there are Greeks in [northern] Greece, immediately across the border from Macedonia, who speak “another language” (Slavic), what the language’s name may be.’ (https://vesti.mk/read/article/https%3A%2F%2Fmakpress.mk%2FHome%2FPostDetails%3FPostId%3D278644). Obviously, it is a rhetorical question, because no Macedonian doubts this language is Macedonian, and until 1949 communist North Greece recognized it under the unambiguous name of Macedonian, too. Thus far, striving to ensure Athens’s indispensable support for Macedonia’s accession to NATO and the EU, the North Macedonian government takes care not to voice any clear opinion on this issue, leaving the naming of this ‘non-Greek language spoken by Greeks’ to Greece alone. This shows that after all the political heavy lifting in North Macedonia, Greece needs to do some more in order to come into the clear.

Bulgarian dialectal area: The Bulgarian nationalist view (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bulgarian_dialects#/media/File:Bulgarian_dialect_map-yus.png)

Bulgarian dialectal area: The Bulgarian nationalist view (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bulgarian_dialects#/media/File:Bulgarian_dialect_map-yus.png)

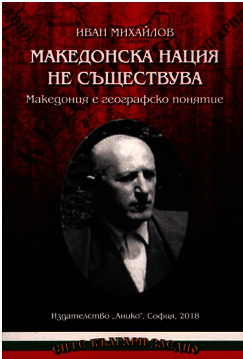

Émigré ideologue of Bulgarian nationalism from Macedonia, Ivan Mihailov’s, most popular work, widely distributed in today’s Bulgaria, titled The Macedonian Nation Does Not Exist: Macedonia is a Geographic Term (Source: https://www.ozone.bg/product/makedonska-natsiya-ne-sashtestvuva-makedoniya-e-geografsko-ponyatie/)

Émigré ideologue of Bulgarian nationalism from Macedonia, Ivan Mihailov’s, most popular work, widely distributed in today’s Bulgaria, titled The Macedonian Nation Does Not Exist: Macedonia is a Geographic Term (Source: https://www.ozone.bg/product/makedonska-natsiya-ne-sashtestvuva-makedoniya-e-geografsko-ponyatie/)

Although the Bulgarian Prime Minister was one of the first European leaders to laud the Prespa Agreement, problems are also brewing in the corner of the Bulgarian-Macedonian relations. During the 1967 talks between Yugoslavia and Bulgaria, in the case of the former country led by the Macedonian politician Krste Crvenkovski, a tradition developed of not mentioning the names of these two languages in which follow-up documents were made, should the pairing happen to be Macedonian and Bulgarian. This unacknowledged arrangement was reinforced after the breakup of Yugoslavia. Bulgaria was the first country to recognize the independence of post-Yugoslav Macedonia (1992), but Sofia does not recognize either the Macedonian nation or the Macedonian language, invariably referring to the latter as the nameless ‘official language’ of Macedonia. The unofficial maps of ‘Greater Bulgaria’ in wide circulation in Bulgaria, show Macedonia as part of this country. The Bulgarian government careful distances itself from such nationalist publications, but on the other hand the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences officially endorses the map of the dialects of the Bulgarian language, which apart from Bulgaria encompasses Macedonia, northern Greece and southeastern Serbia. In this view, Macedonian is another ‘literary standard’ of Bulgarian. However, no Macedonian-language books are on sale in Bulgaria, and Macedonian bookstores reciprocate by not stocking any Bulgarian-language publications (though in the early 2000s a short-lived Bulgarian-language bookshop operated in Skopje).

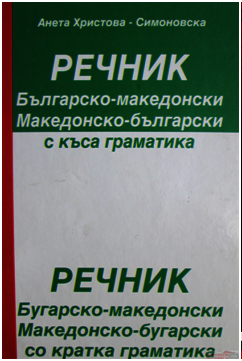

Bilingual Bulgarian-Macedonian and Macedonian-Bulgarian dictionary (2005) (Source: https://kupikniga.mk/product/bugarsko-makedonski-rechnik-makedonsko-bugarski-rechnik-so-kratka-gramatika/)

After Bulgaria joined the EU in 2007, in addition, Sofia silenced any Macedonian angry reactions to its offensive language politics by offering Bulgarian-EU passports to any (Slavophone and Orthodox) Macedonian takers. So far over 70,000 applied for and received Bulgarian citizenship, so about 3.5 percent of Macedonia’s population, or almost 5.5 per cent of all Slavophone Macedonians. The quid pro quo is that Macedonia is one of the poorest states in Europe, and until earlier this year (2019) it was blocked from applying for membership in NATO and the EU. Hence, the Bulgarian passport, whatever a Macedonian applicant might think about political ramifications of her decisions, allows her to find gainful legal employment in western Europe. This leverage will be soon gone after Macedonia has joined the European Union. Perhaps, in order to preempt any reassertion of Skopje’s / Shkup’s lost linguistic positions, in 2017, Sofia leaned hard on Tirana to recognize Albania’s Slavophones as Bulgarians (https://www.novinite.com/articles/184224/Albania+has+Recognized+the+Bulgarian+Minority+in+the+Country). Obviously, no one consulted the concerned themselves, while earlier, these Slavophones had been classified as Macedonians in Albanian censuses and statistics. Sofia continues to build its rarely noticed Bulgarian linguistic-cum-irredentist empire, which extends from southern Moldova to eastern Albania.

2006 mural with Albanian national heroes, located in Skanderberg Square, between the Skopje / Shkup city center and the Čaršija (Source: Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Skanderbeg_Square,_Skopje#/media/File:Sheshi_i_Sk%C3%ABnderbeut_(Shkup)_4.jpg)

2006 mural with Albanian national heroes, located in Skanderberg Square, between the Skopje / Shkup city center and the Čaršija (Source: Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Skanderbeg_Square,_Skopje#/media/File:Sheshi_i_Sk%C3%ABnderbeut_(Shkup)_4.jpg)

Bilingual, Macedonian-Albanian, street name plaque of Skanderberg Square (Source: Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Skanderbeg_Square,_Skopje#/media/File:Sheshi_i_Sk%C3%ABnderbeut_(Shkup)_17.jpg )

Bilingual, Macedonian-Albanian, street name plaque of Skanderberg Square (Source: Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Skanderbeg_Square,_Skopje#/media/File:Sheshi_i_Sk%C3%ABnderbeut_(Shkup)_17.jpg )

A Way Forward: How to Defuse Language?

Much still remains to be done for the sake of de-weaponizing language in Macedonia and across the Balkans, so that it would not stand in the way of peace, stability and prosperity. The frustration of the Macedonians stalled for almost three decades (an entire generation!) by the issue of their country’s disputed name was tremendous. In order to relieve this pent-up energy (and obviously, to capitalize on it politically), in 2014, the VMRO government embarked on a huge construction program in Skopje (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Skopje_2014), where a third of the country’s population live. Many – especially foreign observers – ridicule the relentlessly patriarchal project of claiming Alexander the Great’s empire and mixing it with the medieval Christian, Ottoman and Yugoslav tradition in order to produce a rejuvenated sense of Macedonian identity and purpose. But such projects of free-wheeling cultural bricolage that infuse a national capital’s urbanscape with monuments for much needed identity building or bolstering are not unprecedented. Earlier, Yerevan, or the capital of Armenia, did exactly the same, during both Soviet and post-Soviet periods (https://hy.wikipedia.org/wiki/Երևանի_արձաններ ; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_statues_in_Yerevan).

A 2014 monument located between the city center and the Old Bazaar (Source: Wikipedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Skopje_-_Warrior_Monument.jpg)

A 2014 monument located between the city center and the Old Bazaar (Source: Wikipedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Skopje_-_Warrior_Monument.jpg)

Albanians felt excluded from the 2014 project of the antiquization of Skopje (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antiquization), so they were given some monuments and murals of their own favorite national heroes, all of them invariably males. Luckily, in the spirit of the Ohrid Agreement, since the mid-2000s, the history of Macedonia’s Albanians is duly included in curricula and history textbooks. So this addition did not feel forced. On top of that, the ethnically Albanian but confessionally Catholic, Mother Teresa, has been successfully promoted to the elevated post of Macedonia’s most important 20th-century personality. Thankfully, her monastic fame is neither political, nor military, nor masculine, so the vast majority of Macedonians, in spite of their gender, or ethnic, linguistic and confessional backgrounds, see Mother Teresa as a genuinely unifying figure that allows for transcending the traditional cleavages, alongside the Balkan penchant for unbridled machismo (patriarchalism). Shiny brass plaques in Macedonian and English with Mother Teresa’s thoughts adorn most public buildings across Skopje / Shkup. Edifices of lesser importance sport at least two plaques, while more prominent ones – four.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mother_Teresa_memorial_home,_Skopje.JPG

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mother_Teresa_memorial_home,_Skopje.JPG

In 2009 the Macedonian Prime Minister unveiled the Memorial House of Mother Teresa, located at Skopje’s main pedestrian promenade-cum-high street Makedonija (Macedonia). Four years later, in 2013, the motorway joining Skopje / Shkup with Tetovo / Tetovë was named after Mother Teresa, known as Majka Tereza in Macedonian and Nënë Tereza in Albanian. Tetovo / Tetovë is considered to be the unofficial capital of Macedonia’s Albanians, and also of their culture and language. Symbolically, and true to the Ottoman tradition of peacefully coexisting millets, this Catholic Saint symbolically brings together the country’s Muslims and Orthodox Christians, or the Ottoman millets of Islam and Rum (‘Romans,’ that is, Orthodox Christians).

Memorial House of Mother Teresa, Skopje (Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:НУ_Спомен_куќа_на_Мајка_Тереза_-_04-09-2015_(1).JPG )

Memorial House of Mother Teresa, Skopje (Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:НУ_Спомен_куќа_на_Мајка_Тереза_-_04-09-2015_(1).JPG )

Mother Teresa Motorway (Source: Skôn Skopje, https://www.loveontheroad.nl/goldmine/index.php/2015/11/08/skon-skopje/)

Mother Teresa Motorway (Source: Skôn Skopje, https://www.loveontheroad.nl/goldmine/index.php/2015/11/08/skon-skopje/)

Multilingual logo of the Albanian-medium theater in Tetovo / Tetovë, founded in 2007 (Source: Portalb, https://portalb.mk/171766-teatri-i-tetoves-me-shfaqe-per-te-ndihmuar-te-demtuarit-ne-kumanove/)

Multilingual logo of the Albanian-medium theater in Tetovo / Tetovë, founded in 2007 (Source: Portalb, https://portalb.mk/171766-teatri-i-tetoves-me-shfaqe-per-te-ndihmuar-te-demtuarit-ne-kumanove/)

The oxymoronic ‘classicist Baroque’ of the 2014 historicizing national construction boom made Skopje / Shkup into a curiously interesting city, pleasing to the international traveler’s eye. And more importantly, it seems to bolster the fledgling North Macedonian identity and pride that transcends ethnic, confessional and linguistic particularities. Thankfully, these changes to the capital’s skyline and cityscape mellow the confused historic message of the Yugoslav-time (and somewhat decrepit) Museum of Macedonia and the brand-new Museum of the Macedonian Struggle. Within the scope of this national master narrative, revolutionaries, assassins and terrorists are lauded as fearless and selfless national fighters for a reunified Macedonian nation-state, who aspired to reverse the 1913 partition of their Ottoman country among Bulgaria, Greece and Serbia (Yugoslavia). However, this storyline sits ill at ease with the world’s continuing ‘war on terror,’ which commenced in the wake of Osama bin Laden’s 2001 attack on New York and Pentagon, and now is led by the United States and NATO. Another charming addition to Skopje’s / Shkup’s rapidly changing image, namely, old-fashioned London-style (Routemaster) double-decker buses do little to divert attention away from the ideologically jarring story of Macedonian terrorism absentmindedly cast in the role of North Macedonia’s national history.

Skopje / Shkup double-deckers (Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Skopje_Double_deckers_(cropped).jpg )

Skopje / Shkup double-deckers (Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Skopje_Double_deckers_(cropped).jpg )

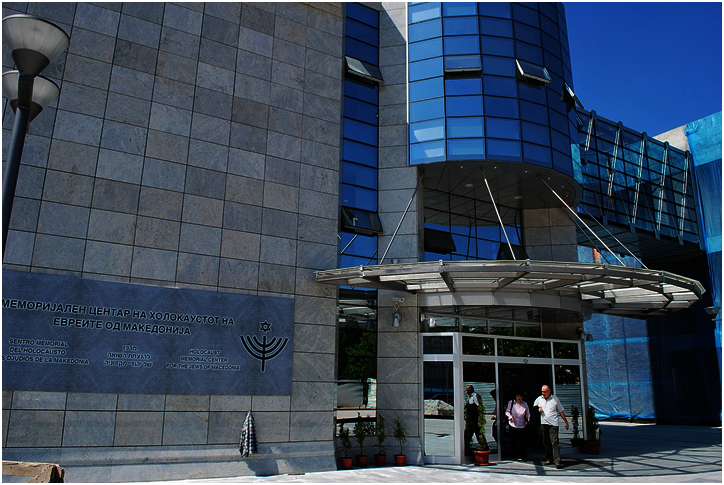

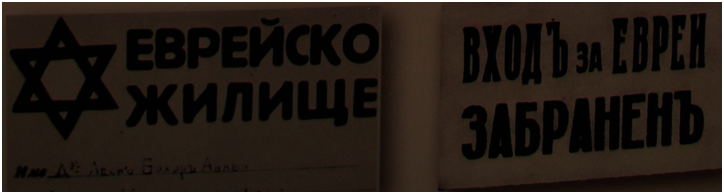

The construction of the Holocaust Memorial Center for the Jews of North Macedonia commenced in 2005. But it took six years before this museum opened its door to visitors in 2011. In order to make up for this long wait, in 2005 a small monument to the victims of the Holocaust in Macedonia was unveiled, poetically named, Symphony of Peace. During World War II, Bulgaria annexed Macedonia, and in order to express gratitude to the Third Reich for this privilege of actualizing the dream of ‘Greater Bulgaria,’ Sofia withheld Bulgarian citizenship from Macedonian Jews, and subsequently sent them to the death camp in Treblinka. In this way, the Ottoman millet of Judaists was wiped out creating a painful absence in the midst of North Macedonian society. The concentrated effort to fill in this deep chasm with remembrance and commemorations resulted in an excellent museum exhibition, with a clear moral message that is lacking in the case of the country’s other historical museums. Serendipitously, the aforementioned Holocaust Center (Museum) offers a uniting national narrative for all North Macedonians. The extermination of Macedonia’s Jews was imposed from outside by the Bulgarian occupants, who also wanted to de-nationalize this country’s Slavophone Orthodox Christian inhabitants (Yugoslav Macedonians) by overhauling them into Bulgarians. On the other hand, Macedonia’s Muslims (mostly Albanians) excelled at saving some Jewish survivors, as they also did even more successfully in wartime Albania and Kosovo. (During World War II, Albania was the sole state occupied by Germany, where not only most of the country’s Jews were saved, but actually their number grew elevenfold, due to the arrival of Jewish refugees coming from neighboring states and elsewhere in central Europe.) In 2017, Skopje’s Institute of Spiritual and Cultural Heritage of the Albanians (Instituti i Trashëgimisë Shpirtërore e Kulturore të Shqiptarëve) published Skender Asani and Albert Ramaj’s trilingual (Albanian, Macedonian and English) monograph Rrugëtimi Patešestvie Journey devoted to Albanians and the wartime Albanian collaborationist administration, who saved Macedonian Jews during the Holocaust. A year later, this Institute followed with a poignant memoir of one such Macedonian survivor saved by Albanians, namely, Mimi Kamhi Ergas-Faraggi. The book is titled My Life Under the Nazi Occupation, and its text is repeated in Albanian, Macedonian and English in order to reach all those interested in the subject in North Macedonian and across the world.

Symphony of Peace monument to the victims of the Holocaust in North Macedonia (Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Скопје-gulapska_trojka.jpg)

Symphony of Peace monument to the victims of the Holocaust in North Macedonia (Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Скопје-gulapska_trojka.jpg)

Holocaust Memorial Center for the Jews of North Macedonia: The information plaque features the museum’s name in Macedonian, Spanyol (Ladino), Hebrew and English (Source: Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holocaust_Memorial_Center_for_the_Jews_of_Macedonia#/media/File:The_Holocaust_Museum_in_Skopje_5.JPG)

Holocaust Memorial Center for the Jews of North Macedonia: The information plaque features the museum’s name in Macedonian, Spanyol (Ladino), Hebrew and English (Source: Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holocaust_Memorial_Center_for_the_Jews_of_Macedonia#/media/File:The_Holocaust_Museum_in_Skopje_5.JPG)

Anti-Semitic Bulgarian-language signs from Macedonia under Bulgarian occupation. The sign on the left reads ‘Jewish house,’ while the other announces ‘No entrance for Jews’ (Source: Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Jews_in_North_Macedonia#/media/File:The_Holocaust_Museum_in_Skopje_31.jpg)

Anti-Semitic Bulgarian-language signs from Macedonia under Bulgarian occupation. The sign on the left reads ‘Jewish house,’ while the other announces ‘No entrance for Jews’ (Source: Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Jews_in_North_Macedonia#/media/File:The_Holocaust_Museum_in_Skopje_31.jpg)

The remembrance about the tragic loss of the Judaist millet – Judaist Macedonians, Macedoners, or Macedonian Jews – is as much a warning to North Macedonia as to Europe. That identity politics, if handled carelessly and made into an absolutist guideline for politics, may yet again lead to war, ethnic cleansing, or genocide. It is a road to nowhere, to perdition. Hence, it is high time in rejuvenated and forward-looking North Macedonia for open-ended reciprocation and free discussion among the country’s all millets. Hopefully, the Holocaust Center may be soon complemented with further museums that would celebrate – in a similarly inclusive and thoughtful manner – North Macedonia’s Albanians, Roma and Turks. The country cannot afford to marginalize or lose another millet to any rashly adopted ideology, be it ethnolinguistic, racialized or ethnoconfessional exclusivism. Likewise, Macedonian-language bookstores, which as a matter of course also stock titles in Croatian, English, French or Serbian should add Albanian-language books to their offer. In turn, Albanian-language bookshops – mostly located in Tetovo / Tetovë and Skopje’s / Shkup’s Old Bazaar – ought to return this favor by including Macedonian volumes on their shelves. Books allow for transcending the narrow confines of the compartment of one’s language or religion, and foster the unrestricted flow of ideas, which is the foundation of the freedom of speech, democracy and stability.

Jan Józef Lipski, a precursor and one of the foremost figures of the German-Polish reconciliation, wisely noticed that ‘[w]e must tell all to each other […]. Without this the burden of the past will not let us enter a common future’ (Musimy powiedzieć sobie wszystko […]. Bez tego ciężar przeszłości nie pozwoli nam wejść we wspólną przyszłość).[1] Hopefully, this truth will not be lost on North Macedonia’s leaders, so they follow this message and encourage the building of a prosperous and peaceful North Macedonia for all its inhabitants in united Europe.

March 2019

[1] Lipski, Jan Józef. 1996 [1985]. Odprężenie i pojednanie. Polemika z Günterem Grassem (pp 89-93). In: Jan Józef Lipski. Powiedzieć sobie wszystko…. Eseje o sąsiedztwie polsko-niemieckim / Wir müssen uns alles sagen…. Essays zur deutsch-polnischen Nachbarschaft [edited by Georg Ziegler]. Gliwice and Warsaw: Wydawnictwo „Wokół Nas” and Wydawnictwo Polsko-Niemieckie, pp 89-90.