Tomasz Kamusella: Liquidating a Language

Tomasz Kamusella

University of St Andrews

Cultural Genocide

Last academic year (2019/2020), the students who attended my module on ethnic cleansing and genocide, grappled with the concept of cultural genocide. One of the related issues they discussed was the destruction of a language employed by the target group as a marker of this group’s ethnic distinctiveness. With a fresh memory of the seminar on the Jewish Holocaust, the students quickly concluded that a full-scale genocide of an entire ethnic group usually entails the destruction of this group’s language. Fine, I agreed, but we were to talk about ‘cultural genocide,’ not the physical liquidation of all the members of an ethnic group, which is the regular meaning of the unqualified term ‘genocide.’

The German extermination of Europe’s Jews still on their mind, the students proposed the fate of Hebrew as a language. According to the standard, though simplistic, analysis, Hebrew fizzled out from use by the 2nd century CE. But the process was gradual, lasting around 800 years. It opened with the Babylonian conquest of the Jewish homeland in the 6th century BCE. In the subsequent period, known as the Babylonian captivity, Jews acquired the empire’s closely related Semitic language of Aramaic. Afterward Greek became widespread among the Jews in the wake of Alexander the Great’s conquests that resulted in a Hellenic Empire. However, no power in control of the Jewish lands implemented a language policy that would consciously seek such a replacement of the Jewish ethnic language of Hebrew with Aramaic or Greek. What is more, most Jews accepted Aramaic as yet another Jewish language. In addition, unlike the popular opinion proposes, Hebrew did not become a ‘dead’ language. Its command was passed from one generation of Jewish males to another in yeshivas. Hebrew continued to function as a language of scholarly discourse and business communication. On this basis, at the turn of the 20th century, the Zionist movement adopted the program of making the functionally limited Hebrew into the Jewish national language that would become the leading medium of everyday communication among the Jews in Palestine.

Having been faced with this dilemma of Hebrew that never was a dead language, the students suggested that maybe it is impossible to eradicate a language without destroying its speakers, that is, the language’s speech community. In turn, I asked them whether in such a situation the concept of cultural genocide was superfluous. Why to talk then about destroying a culture or a language, should the indispensable prerequisite of it be the genocide of a target ethnic group, who speak such a language and practice customs of a given culture. The students demurred that they needed to look harder for a suitable case of the destruction of a language, which did not necessitate the destruction of this language’s speech community.

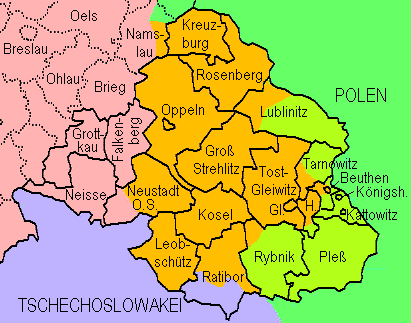

Upper Silesia: Between Germany and Poland

This discussion was hard-going, so I suggested that they focus on the case of Upper Silesia, or a historic region, which was part of Germany until the end of the Second World War in 1945. In the wake of the Great War, this German region (fully contained within the Land of Prussia) was divided between Germany and Poland in 1922. The latter country received the puny eastern sliver of Upper Silesia, which however, contained most of the region’s industrial basin with half of the Upper Silesian population. In 1939, the Third Reich retook this easternmost part of Upper Silesia lost in 1922, and occupied western Poland in alliance with the Soviet Union that seized the eastern half of this country. But now let us forget about the geopolitical complications, so we could have a clearer look at interwar Germany’s section of Upper Silesia with its 1 million inhabitants who remained German citizens until 1945.

(Source: Ulamm / CC BY, Wiki-Media Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Oberschlesien_1921.png)

From other parts of the deutsche Ostgebiete (eastern German territories, located east of the Oder-Neisse line) passed to postwar Poland on the basis of the Potsdam Agreement between Britain, the Soviet Union and the United States, German citizens – seen as Germans – were expelled to the diminished postwar Germany during the latter half of the 1940s. The exceptions were Upper Silesia and Mazuria (southern East Prussia). However, we do not consider the latter case here.

Language Politics

How come that the Polish communist authorities, with the Kremlin’s full support, decided to retain almost a million of German citizens living in the territory of interwar Germany’s section of Upper Silesia? Unlike in the case of the German citizens elsewhere in the deutsche Ostgebiete, Warsaw declared German Upper Silesia’s German citizens to be ‘Autochthons’ (autochtoni). The Polish authorities invented this Greek neologism especially for claiming this population for the ethnolinguistically defined Polish nation on the spurious basis that such Autochthons were indigenous to Upper Silesia. But the German citizens living in other areas of the deutsche Ostgebiete, in their vast majority, were also indigenous (Latin term), that is, autochthonous (Greek term), to their regions. What counted was language, they spoke German only, while in the eyes of the Polish propaganda, Upper Silesia’s German citizens presumably spoke ‘Polish,’ or at least used to speak it ‘until recently.’

In reality, all the inhabitants of interwar Germany’s section of Upper Silesia spoke German, though around half of them also talked or had a passive command of the local Slavic dialect, nowadays known as the Silesian language. That was the sole tenuous connection of the group to Polishness, their speech as close, or as distant, to standard Polish as Czech or Slovak. Yet, Warsaw did not claim Czechoslovakia for communist Poland on the grounds of linguistic affinity. According to Polish officials the decisive argument was the fact that the German authorities themselves dubbed the concerned population’s speech as ‘Polish’ in the census statistics during the second half of the 19th century. This development is connected to the Breslau (Wrocław) Suffragan Bishop, Bernhard Bogedain’s, 1849 decision to introduce Polish as a medium of education in elementary schools where Slavophones predominated across Upper Silesia, or mainly in the eastern half of this region. In Prussia (Germany since 1871) schools were run by the Protestant and Catholic churches until 1918. Neither Bogedain, nor Slavic-speaking Silesians did see themselves as Poles. In their eyes Poles lived in the east, namely, across the state border in Russia’s Kingdom of Poland and in Austria-Hungary’s Crownland of Galicia.

The rationale of introducing Polish as a language of instruction was the fact that it was closer to the Slavic language of Silesian than German. Polish allowed to bridge this gap between Silesian and German, with an eye to facilitating the acquisition of German by Silesian-speaking children. Afterward, in the higher grades of elementary school, German fully replaced Polish as the leading medium of education. Following the founding of the German Empire as an ethnolinguistic German nation-state in 1871, the use of Polish in Upper Silesia’s educational system was fully contained to the initial two or three grades of elementary education, and gradually curbed further. After 1905, Polish was eventually excluded from the region’s schools, because between the 1870s and the turn of the 20th century two generations of all Silesian-speakers had successfully received education through the medium of German. Afterward, Polish, alongside German, remained a language of pastoral services in Upper Silesia’s Catholic churches. However, it should be emphasized that Latin continued as the sole language of Catholic liturgy until the turn of the 1970s.

In the wake of the 1922 division of Upper Silesia, under the auspices and international control of the League of Nations, minority schools and organizations were founded across Upper Silesia, namely, Polish ones in the German section of the region, and their German counterparts in the Polish section. In addition, almost 200,000 pro-German Silesians left the Polish section for Germany, and over 100,000 pro-Polish Silesians the German section for Poland. Hence the German-speaking character of the German section deepened, while the dominance of Polish began to be established across the Polish section. The transitional provision of official bilingualism in Polish and German lasted for a mere four years (1922-1926), and afterward Polish fully replaced German in public life across interwar Poland’s section of the region.

As mentioned above, during World War II, all of Upper Silesia, along occupied western Poland, was incorporated directly into wartime Germany. In turn, German fully superseded Polish in public life. Neither was the Silesian language tolerated in Upper Silesia, because Berlin saw it as a ‘kind of Polish.’ When my late Fater (‘father’ in Silesian) was about to go to school in September 1941, his parents and siblings made sure to speak exclusively in German when he was around. Meanwhile, Ōma (‘granny’ in Silesian) continued to pray in German and reading her prayer book Weg zum Himmel (Way to Heaven), while Ōpa (‘grandad’ in Silesian) did the same in Polish and perused the Polish-language edition of the very same prayer book, or Droga do Nieba. At home, they mostly spoke in Silesian. No heaven, however, was to be found in the war inferno.

In the wake of the conflict, Poland took over all Upper Silesia. Warsaw retained, the vast majority of the region’s inhabitants, because first of all, they were indispensable for staffing continental Europe’s second largest industrial basin after the Ruhr in western Germany. Both Wehrmacht and Red Army had made sure to not damage this basin, as at that time it had been the sole source of petrol (made from coal) in this part of Europe. Postwar Poland had no pool of qualified workers to replace the Upper Silesian workforce overnight. Another reason which compelled the Polish authorities to retain the Autochthons was the fact that in interwar Poland’s eastern territories annexed by the Soviet Union the number of ethnic Poles was insufficient to fully replace the Germans who were earmarked for expulsion from the deutsche Ostgebiete to postwar Germany. It would have been a propaganda disaster for Warsaw and the Kremlin to have numerous towns and villages permanently emptied of population across the western half of postwar Poland.

Hence, Upper Silesia’s Autochthons had no choice and were compelled to stay put, even if some considered leaving for territorially shrunk postwar Germany. Officially, they were ‘Poles,’ but the bureaucratic label of ‘Autochthons’ was to caution the Polish administration that in reality they were none other than ‘crypto-Germans’ (krypto-Niemcy). The Autochthons’ German citizenship was initially replaced with the temporary Polish citizenship that could be revoked at any time. In order to receive a permanent version of this citizenship, they were compelled to undergo the bureaucratic process of ‘national verification’ (weryfikacja narodowościowa[1]), which was to investigate, and hopefully reconfirm, their ethnolinguistically construed Polishness. If successfully verified, an Autochthon became a ‘verified one’ (zweryfikowany), just another bureaucratic label, which the Polish administration interpreted as a code word for indispensable crypto-Germans in Upper Silesia. Should an opportunity appear Autochthons-turned-the-verified would be either allowed to or compelled to leave for Germany. Cumulatively, almost 800,000 did (including children born after the war), especially during the détente of 1970s and at the turn of the 1990s, when communism collapsed.

Opole Region (Województwo Opolskie) was built from two-thirds of the territories of interwar Germany’s section of Upper Silesia. After the war Autochthons accounted for 80 percent of the region’s population. Due to the rationed emigration and expulsions during the communist period, their share in the populace gradually dropped to a third of Opole Region’s inhabitants in the 1990s. In their majority, especially the old and middle-age generations identify as Germans. Until the end of communism, Warsaw claimed that there were not any substantial national minorities in the Polish People’s Republic, let alone any Germans. Finally, after the first postcommunist government took power, in 1990 the authorities acknowledged the existence of a German minority in Poland.

It turned out that this German minority, with 300-400,000 members at that time, closely corresponded to Opole Region’s Autochthons. Polish ethnonationalists triumphed, pointing out that they had been all the time right referring to Autochthons with the pejorative ‘crypto-Germans.’ Fortunately, Bonn and Warsaw took a more cautious approach to this issue. Germany, in addition to the staggering expense of reunification, had been already dealing with a huge wave of ethnic Germans arriving from Romania and post-Soviet countries. Thus, the German government was interested in making sure that Upper Silesian Germans would remain in their homeland. On the other hand, the Polish government feared that a possible mass emigration of a third of the population from Opole Region would cause a dual, demographic and economic, collapse of the region. Subsequently, an informal deal was struck between the two countries, which breached both German and Polish citizenship regulations. Germany waived the necessity of residency in the country as the precondition for ethnic Germans to apply for German citizenship. In reciprocation, Warsaw consented that German consulates would issue Polish citizens (that is, Autochthons) with German citizenship in contravention of the Polish law, which then still banned dual citizenship.

(Source: Jonny84 / CC BY-SA, Wiki-Media Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:German_Minority_Upper_Silesia.png)

As a result, a quarter of a million Polish citizens obtained German citizenship without having to leave Poland. The German passport gave its holders access to the job markets in Germany and across the European Union 14 years prior to Poland’s accession to the EU in 2004. This solution prevented a demographic disaster in Opole Region and revitalized its rural economy overnight with no investment extended from the Polish budget. Basically, Autochthons-cum-Germans stayed put, but most males of working age found jobs as seasonal laborers in Germany and the Netherlands. Their remittances turned Opole Region’s countryside into Poland’s most developed rural area.

Where Is the Language?

According to the 2011 Polish census, 150,000 Germans live in present-day Poland, the vast majority of them in Opole Region. However, neither in this region nor elsewhere in Poland is there a city quarter, town, village or even a hamlet where German would function as a language of everyday communication. In 1945 all Autochthons spoke German, while now only lone individuals who learned this language in school or working seasonally in Germany. At present it is Silesian that functions as the main community language in the majority of the localities where Upper Silesian Germans live. In addition, those who continued education in secondary schools and universities also became bilingual in Polish. This sociolinguistic reality is at odds with the ideal of ethnolinguistic nationalism that dominates throughout central Europe. In accordance with this ideology one should belong to this nation whose language one speaks. Upper Silesian Germans do not speak German, but belong to the German nation.

(Source: Aotearoa / CC BY, Wiki-Media Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Łubowice_tablica.jpg)

Opole Region’s Germans existed in 1945 and exist today. In communist Poland their existence was denied, yet their rationed emigration and periodic expulsions to Germany belied Warsaw’s claim. What has been, however, lost is the German language itself. Hence, it is a clear case of the destruction of a group’s language, without exterminating the group’s members.

How was it done? Claiming Autochthons as Poles and nationally verifying them as such was not enough. The Polish authorities pledged to remove the ‘ugly German façade’ that continued to besmirch the eternal Polishness of Autochthons. Forced Polonization was the obvious answer. It came in the form of the two related policies of de-Germanization (odniemczanie) and re-Polonization (repolonizacja). The role of de-Germanization was to remove any traces of Germanness from public and private spheres. First, all the place-names were Polonized overnight in 1945. In 1946 this practice was extended to the ‘insufficiently Polish’ names and surnames of Autochthons. Second, all the German-language shop signs and public notices were replaced with Polish ones. German words and phrases on gravestones were meticulously chiseled our or cemented over. Most German books and newspapers were pulped, while those deemed as ‘valuable’ were deposited in special purpose libraries and warehouses, to which Autochthons had no access. Third, German was replaced overnight with Polish as the sole medium of administration, education and legal public life. No transitional policy of official bilingualism was considered.

The German façade already torn away, it was necessary to re-Polonize Autochthons as individuals on the assumption that in their heart of hearts they had always been Poles. The policy of re-Polonization usually meant Polish language courses for adults and remedial Polish language lessons for schoolchildren. From my Fater’s perspective as a kid, it was a complete reversal to what he had experienced during the war. Now his parents and siblings made sure to speak Silesian only, when he was around, so that Fater could continue with his education. Officially, in Poland, Silesian was and still is considered to be a dialect of the Polish language. Yet, in reality, it is seen as ‘faulty (that is, Germanized) Polish,’ or even a dialect of German, and a kind of ‘crypto-German.’ Hence, talking in Silesian was not enough. Fater had to attend his fourth grade twice in 1945/1946 and 1946/1947, before his teachers decided that his Polish was acceptable, cleansed of both ‘ugly Germanisms and Silesianisms.’

Communist Poland’s security forces (Urząd Bezpieczeństwa, UB) were tasked with overseeing, and if need be, enforcing this vast action of forced Polonization. If a family was reported that they spoke too much German, first, they were fined. Second, the parents were fired from their jobs. And if they happened to be farmers, their farm was requisitioned. Further persisting in the ‘national error’ of talking in German resulted in the expulsion of their children from school. Next step in this gradation of punishments was the loss of the family’s house or apartment. Finally, a forced labor concentration camp for ‘linguistic criminals’ operated in Gliwice (Gleiwitz) until the turn of the 1950s.

During the latter half of the 1950s, Autochthonous villages and towns fell eerily silent, the inhabitants wary of ubiquitous UB spies and informers. Autochthons preferred not to talk, when they were unable to find necessary Silesian or Polish words. The strict enforcement of the never declared ban on German gradually lessened in the 1950s. However, half a decade of totalitarian terror was sufficient to suppress the use of German as a language of everyday communication across Upper Silesia. In families most chose to not talk in this language to their children, so the intergenerational transmission of German was also severed. Those who found it easiest to express themselves in German, did it in secret with their spouses, adult relatives and friends. It is estimated that not more than a thousand families (about 5,000 people in total) made sure to pass this language to their children born in communist Poland. Yet, a year or two before children were to start attending elementary school at the age of seven, their parents began talking to such a child exclusively in Silesian or Polish, so that their daughter or son would not face ostracism for not knowing Polish. As a result, the German of these children remained often stunted at the level of a five-year-old kid.

The situation lasted for half a century. It was forbidden to offer German even as a school subject in schools located on the historical territory of Upper Silesia. When the first-ever university was founded in Upper Silesia in 1968, namely the University of Silesia (Uniwersytet Śląski), the dilemma was what to do with German. A university with no department of Germanic languages would be a laughing stock in central Europe. The solution was to place all the university’s departments of languages in a branch located in Sosnowiec, that is, immediately next to the historical border of Upper Silesia, but safely outside the region.

In 1990 Poland finally recognized the German minority in Upper Silesia. A hope was for a revival of the intergenerational transmission of German in the region’s villages and towns with German majorities. But Warsaw, despite the aforementioned concessions on the issuance of German citizenship to Polish citizens, was not ready to extend this ‘nationally permissive’ approach to language. Behind the scenes it was demanded that substantial aid flowing during the 1990s from Germany for the needs of Upper Silesia’s Germans would be spent on improving the infrastructure, not on the construction and maintenance of minority schools. The old generation with a native command of German, who had attended German schools in the 1930s and 1940s, were able to reignite such a transmission.

(Source: School’s facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/zsdsolarnia/)

Now, three decades later, in 2020, it is too late, most of them are either dead, senile or understandable not interested in teaching in school in their 80s or 90s. Like there is not a single locality or city quarter in Upper Silesia where German would be a community language of everyday communication, similarly no German-medium minority exist in the region. A mere three German minority schools are bilingual, though in an asymmetric manner, more subjects are taught in Polish than in German.[2]

The liquidation of the German language in Upper Silesia has been sealed. On the other hand, the region’s Germans survive, less their ethnic language. Is it not a clear-cut case of cultural or linguistic genocide? Totalitarianism was and still is the necessary condition for effecting such a result. The state and its functionaries are needed who would readily and permanently disregard the concerned and their wishes, while imposing on the target population whatever the powers that be intend. Totalitarianism allows for creating appropriately oppressive condition when speaking one’s native language can cost one’s livelihood, leading to the swift switch to the imposed language for everyday communication.

June 2020

[1] Literally, the Polish term means ‘the verification of a person’s nationality,’ that is, the fact (or feeling) of belonging to an ethnolinguistically defined nation (group of people) by the virtue of displaying required ethnic markers, such as, a language, religion, clothing, surname, or a given name.

[2] Mniejszość niemiecka chce więcej szkół dwujęzycznych. 2018. Newsweek Polska. 28 Feb. https://www.newsweek.pl/polska/mniejszosc-niemiecka-chce-wiecej-szkol-dwujezycznych. Accessed: Jun 24, 2020.