The Rezian language. The lexicon of contact – the unwritten history

The Rezian language

The lexicon of contact – the unwritten history

Nadia Clemente

Abstract

The Resians inhabit a valley – Val Resia – belonging to the geographical, administrative, social and cultural area of Friuli (Italy). With the Friulans – people of Romance lineage and culture – Resians shared history, from the first settlement in the early Middle Ages, then with the era of the Patriarchate of Aquileia and through all the historical vicissitudes up to the annexation to the Kingdom of Italy , then the Italian Republic. Resians interacted with Friulians of the neighbouring villages and towns, always remaining isolated in their alpine valley, almost inaccessible and without a carriage road until 1838. From the culture, language and society of the Friulians, more evolved and wealthy, the Resians have assimilated the principles of a new agricultural, sylvan-pastoral economy, as shown by the Romance loanwords present in Resian and analyzed here, furthermore, the improvements made to the houses, to make the Spartan living conditions of the Resians more comfortable, testify to the presence of Friulian culture.

The reason for the many Germanisms in the Resian area still remains to be explained scientifically and on a precise and exhaustive historical basis.

1.Introduction

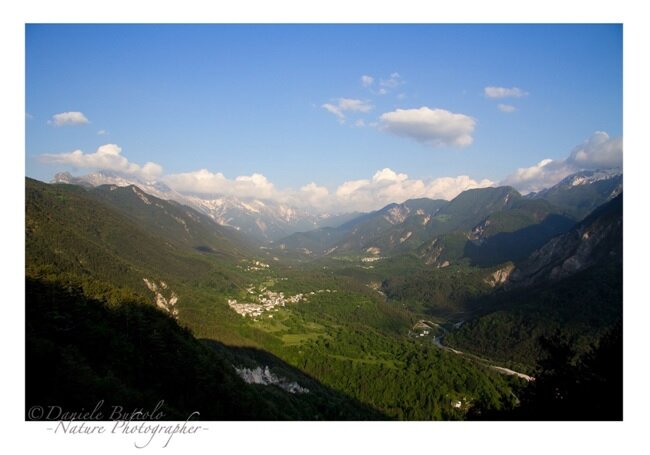

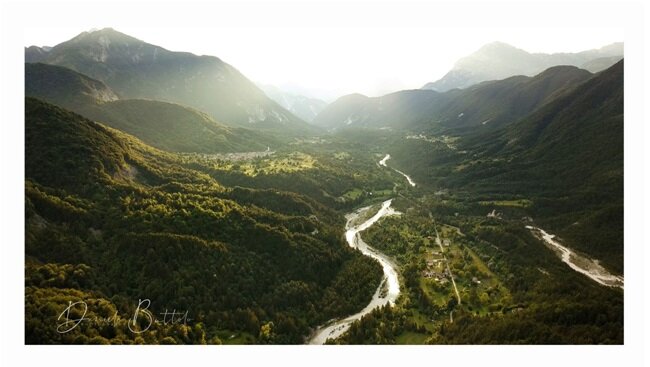

Rezia is an alpine valley, wedged for about 20 kilometers between the Alps and the Julian Pre-Alps, at the extreme north-eastern border of Italy. It is located in the Friuli area and closed to the east by the mountain massif of Mount Canin (2587 meters above sea level). In the main valley the inhabitants are distributed in the five hamlets: San Giorgio/Bila, Gniva/Njiva, Oseacco/Osoána and Stolvizza/Solbiza) and Prato di Rezia/Ravanza – considered the capital. In a small adjacent valley, Uccea/Učja is only inhabited in the summer.

The official history of Rezia tells that[1]:

“At the end of the sixth century. A.D., the Vendes emigrated from Luzatia, a region between present-day Germany and Poland to Carinthia and went as far as the Channel del Ferro and Rezia Valley. These populations of Slavic speaking shepherds, arrived here to escape the tyranny of the Avars and settled in a relatively stable way. The Longobards tolerated the presence of the Vendas even though on some occasions supremacy was established by the use of force, but the biggest problems consisted of the raids of the Avars who descended several times in Friuli. The sixth century is also characterized by the foundation of the Patriarchate of Aquileia whose jurisdiction included the whole region therefore also Val Rezia.

The periods of Frankish and Germanic domination followed that of the Longobards. During and after these reigns, the administration of the region was curated by the Patriarchate of Aquileia and lasted throughout the medieval age. The first historical documents concerning Rezia date back to the end of the 11th century when a feudal lord, Cacellino, ceded the whole area of Val Fella and Val Rezia to the Patriarch of Aquileia and, as a result of this transfer, the abbey of Moggio was built (1118 – 1120). The administration of the territory then passed to the Benedictine monks who looked after the interests of the Patriarchate until the fifteenth century, and then became part of the Maritime Republic of Venice up to the Napoleonic campaigns.”

Later Resia, like all the surrounding municipalities and territories, was included in the Lombard-Veneto Kingdom (1815-1866) a dependency of the Austrian Empire and, after the Independence Wars, became part of the Kingdom of Italy (1866).

Val Rezia, shut in between high mountains, has only one natural outlet, at Resiutta, a village located on the Roman road that connected Italy to the Noricum, the artery, later known as the ‘great Vienna-Milan road’. Over the centuries this road has witnessed the passage[2] of travellers, merchants, students, pilgrims, clerics, writers, scientists, armies, kings and courtiers from Eastern Europe; Poland, Slovakia, Russia reached Italy and Rome. And it was on that road that Count Jan Potocki was travelling in the year 1790, when he heard about a Slavic community that had remained isolated and unknown and wanted to know more, reaching Rezia.

A report of the visit remained in the manuscript, translated into German by Kopitar, then inserted in Die Slaven im Thale Resia – Vaterländische Blätter für den österreichischen Kaiserstaat. Jahgr. IX, 1816. Just this publication attracted the attention of various Slavic scholars such as Dobrovsky and I.I. Sreznevskij. After this first publication the Slav world and Slavists came to know the Rezians and began to take an interest in them.

The first in-depth analysis of the Rezian language and culture is due to the studies of Jan. I.N. Baudouin de Courtenay, who arrived in Rezia in 1873.

Baudouin de Courtenay, with regard to the origins of Rezian and Rezians, wrote: “Three different Slavic families live In the Rezia Valley, and in part in Uccea, they came from various places, and perhaps even at different times, one of them used the dialect of Bila (S. Giorgio) in its various aspects. The second family lives in Gniva, in Stolvizza. Finally, the Rezians of Oseacco, of Uccea owe their origin to the third family. The common differences between the dialect of these families should have been much greater in the beginning than it is at present, or at least they should have been the germ of much greater differences. But these differences waned, on the one hand due to the identical foreign influence that gave all the dialects the imprint of a common individuality, on the other hand for the continuous relationships, for the geographic commonality and for the sense of belonging to the same Rezian family, considered by the Rezians themselves as something quite particular, compared to the Roman and Slavic stock in immediate contact with them. ” (Опыт фонетики резьянских говоров, Warsaw – Peterburg 1875 §. 299)

2.The Rezian language

The geographic conformation of the valley, closed on all sides, with the only carriage access, consisting of a road built in 1838, has determined and conditioned the life and historical events of the valley, but at the same time has favoured the maintenance of the language, derived from ancient Slavic, which still preserves interesting archaic features and various other elements of interest even today, while the same condition of marginalization has allowed the development and maintenance of unique songs, dances and oral traditions. (see dances in youtube, and photo n. 3)

The Rezian language was born and developed in this valley,

“В те времена в этом ареале, крoме романских языковых разновидноcтeй, важную роль играл также и немецкий язык. С другой cтороны, контакт сo словенским языком и его говорами был всегда очен ограничен из-за высоких гор, разделяюших рeзянскую область от Словении.”[3]

The traditions and Rezian language has been handed down from generation to generation exclusively in oral form, and, under various social and historical influences has adapted and enclosed the path of its people, of Slavic origin, but always a part of the sphere of influence of Friuli, territory with language and tradition Romance.

The contact with Friulian society, the new circumstances, the new way of life and the stimuli for development and progress, gradually penetrated into the Resian one and the lexicon which is “the point of greatest reactivity of a language to events of the society that uses it, which is born and dies almost exclusively for cultural and social reasons or through motives of custom or prestige”[4], bears witness to the direct and continuous interaction between the two communities.

In the last fifty years Italian culture, predominant through schooling, the development of the media, technology and the new socio-economic model, has affected and contaminated the original language. To investigate the condition of relative integrity of Resian it is useful to consult the material collected by Baudouin de Courtenay, in the years 1873 and following, and published by him in various texts, almost all of which can be consulted online[5].

3.The archaic traits of the Rezian language

In this chapter we want to present the peculiarities of the Resian, analyzing some ancient terms, which contain the echoes of the past almost as if preserved ina casket, and demonstrate the living conditions and habits of the first inhabitants of the Valley.

wlëst ‘to enter’

wlëst ‘to enter’ [wližön, wližëš], still retains its evident origin from the paleoslavian вълѣсти6 (вълѣзѫ, вълѣзеши), with the same meaning; the corresponding verb is wlažät [wlažän, wlažäš], also from the Paleoslavian вълазити [6] (вълажон, влазиши). The term -lest, in the Slavic languages, means ‘crawling’ and this way of proceeding ‘crawling’ or on all fours, suggest the image of very low doors and underground houses, renders the idea which forced the inhabitants to bend down in order to enter or exit. We know that for “the Slavs of the protopatry… the typical sunken earth huts or houses dug into the ground, acted as dwellings everywhere”. (zemljanki or half-zemljanki)[7]”. In Rezia we still have the memory of houses, built under street level with one or two steps to enter in them, unfortunately the last examples of original Resian architecture were destroyed by the disastrous earthquake of 1976.

In the Resian language –lest is generative of the following verbs: vilëst ‘to go out’, wlëst ‘to enter’, riślëst ‘to descend’, nalëst ‘to find’, śalëst ‘to happen, to intrude’. In the sequence of verbs, the Italian speaker notes the absence of a term indicating the action of ‘going up’. It is a common with almost all Slavic languages which, instead of a single term, uses the combination ‘go up’: in Croatian ‘ići gore’, in Czech ‘jit nahoru’, in Polish ‘iść do góru’, in Slovak ‘ ist ̍hore ‘, in Slovenian’ iti gor ‘.

In Rezian instead we say:

tet wòn ‘to go up’

It is observed that only in Resian the preposition won is used, deriving from the Paleoslavian вънъ ‘out’; it therefore follows that in Resian, tet won coincided with ‘going out’. The preposition goré[8] ‘up’ is also present in Rezian, but has not been used to represent the action ‘to go up’; from this it can be deduced that the particular environmental conditions led to the choice of won ‘out’ instead of goré ‘up’. We have confirmed this by analyzing the following combination, which means ‘to go out: tet won ś-wûna, ‘to go out (for example: into the courtyard)’ and ś-wûna derives from *z-вънa, [z + genitivo di вънъ]. Literally the simple action of ‘getting out’ involving a climb and, from above, a move away to get outside. The comparison with tet dölu ‘going down’ is also interesting, which also includes the expression, tet dö’ ś dolá ‘going all the way down’, or ta- dö’ ś dolá ‘down there at the bottom’ (state in place).

To complete this brief survey on the preposition won, let’s also evaluate the other phrases that contain it:

stat tu-wne ‘to stay up there’; tu-wne complement of state in place;

stat wne’ ‘to stay alert, to be vigilant (during he night)’. In Rezian this action is only possible during the night and would make no sense in daylight. Also in this case stat wne’ it suggests a real condition, that is the nocturnal vigil, we hypothesize, to guard one’s home and property.

ëro/jëro ‘priest’ and lanita ‘cheek’

These are the linguistic treasures of the Resian. The two terms are present in the Paleoslav canon, the ecclesiastical codes manuscript dating back to the X-XI century, which in turn were copies of texts used in previous centuries, therefore it can be said with certainty that ëro / jëro and lanita have been in use in Rezian, in an unaltered form, for more than 1000 years.

ëro/jero [9] – ‘priest’ [<иѥреи, иѥрѣи,6 (иерей, священник)]. Still in use today, we also find it documented in the book of di Izmail I. Sreznevskij[10]: “Общее названіе для всѣхъ священников есть jœ́ro или œ́rо”. For an entirety of the data, we report a passage from the Paleoslavian Canon, from the Gospel of Luke 17,14 ‘шьдшъе покажите сѧ іереомъ’6.

lanita – ‘cheek’, [<ланита6, щека]; the term is also documented in the Old Russian Vocabulary of Sreznevskij[11]. This appellative is still used in Resian with the primitive meaning of ‘cheek’, while in the villages south of Rezia (valleys of the Torre) it has changed the semantic value to ‘ face’. In the Paleoslav canon we find it in the Gospel of John 19,36: биѣахѫ і по ланитама, e in Supr6: слъзꙑ вьрѧшта капаахѫ по ланитама на зємьѭ.

This last image of the ‘tears running down the cheeks’ echoes in a Rezian song:

Da nüna, nüna, nüniza, riślëste dö s te ćanibe śi suśi dö po laniteh, ka mata jtet sa śveśat kwop, ‘Oh wives, wives, little wives, come down from the room with tears running down your cheeks, you have to go and join (get married).’

zledat/zgledat ‘to count’

We have noticed that in the Slavic languages there is no original verb to express the action of ‘counting’, as if the term was not used in ancient Slavic. From a check, we find: in Russian ‘считать’’, in Slovenian’‘šteti’, in Slovak ‘ počítati ̍, in Czech’ ‘počítat’’, in Croatian’‘brojati’ ‘, in Polish’‘liczyć’. In Rezian śledat/śgledat ‘to count’ probably derives from * raz-gledat, where the prefix raz– means ‘separation’, ‘fractionation’. Thus it follows that ‘looking separately’ fully interprets the action of ‘counting’.

Even numbering has its own peculiarities in Resian:

from 1 to 19

dän, dwa, trï/trïje, štire/štirje, pet, šëjst, sëdän, ösän, dëvät, dësät, dänest, dwanest, trïnest, štärnest, petnest, šëjstnest, sëdanest, ösanest, dëvatnest,

20 = dwiste, 30 = trïste, [more similar to the Russian двести, триста or the Slovenian ‘dvesto e tristo’ (200-300), rather than ‘двенадцать’ or ‘тринадцать’, (20-30), etc.]

20+1, 20+2…39, dwiste (a)nu dän, dwiste (a)nu dwa…

40 = štrede < štiri rède[12], lett. ‘four rows’;

50 = patërduw < pet ridúw, lett. ‘five rows’;

40+1+2, 50+1+2, štrede patërduw (a)nu dän, (a)nu dwa,

from 60 onwards the calculation is of the vigesimal type:

60 = 3 x 20, trïkrät dwiste; 70 = 3 x 20 + 10, trïkrät dwiste anu dësät;

80 = 4 x 20, štirkrät dwiste; 95 = 4 x 20 + 15, štirkrät dwiste anu petnest.

100 stūw,

from 200 onwards Resian has relied on Friulian loan words

200 dwa čantanarja, 300 trï čantanarja; 1000 den mijār, 2000 dwa mijarja, 3000 trï mijarija.

śubjön ‘troubled, lost, confused’

In Rezian, the word възлюблѭ7, [< възлюбити] ‘I’m in love’, he has become śubjön ‘troubled, lost, confused’. The original verb fully justifies the adjective, it is known that the condition of ‘falling in love’ also causes an altered and deconcentrated state of consciousness. This hypothesis, apparently an imaginative stretch, needs confirmation, it would be interesting to consult an etymological dictionary of the Slavic language, unfortunately, I do not have one available.

romonet ‘to speak’

The term has an assonance with the verb ‘ruminate’, typical of herbivores. This match might seem bizarre, but it already Cicerone (Att. 2, 12, 2)[13] uses the Latin term ruminatio ‘ruminating’ with the figurative meaning of ‘to speak’, i.e. ruminatio cotidiana ‘going over the same speeches every day’.

It is difficult to prove the origin of this term in the Rezian due to the absence of written evidence. We can only hope that some independent scholars can investigate and reconstruct the evolution of the Rezian language.

4.The lexicon of contact and the unwritten history

Romance loanwords

A peculiarity of the Resian is the large amount of Romance loanwords in the lexicon, justified by the geographical location of the Valley, assimilated in the Friulian territory. In this loanword review we want to examine the contribution of the Romance culture in Resian and, in order to facilitate comparison, the items have been divided into semantic sectors and categories. The lexicon concerning the terminology of the ‘house’ and the ‘territory’ will be compared, using only the most common terms and omitting those that are not in use. In addition to the house as an essential shelter, the useage and knowledge of the territory was fundamental for the Resians, from which they derived their only certain source of sustenance. The territory of Resia extends for about 20 square kilometers, positioned between two mountain chains.

In this area, the meadows were mowed to provide hay for the dairy animals. The few fields lying on the rare plateaus, always too sterile and miserly, were used to ensure a minimum sustenance for families, the narrow streets and paths were essential to orient oneself in the wooded and above all rocky landscape, perched on the slopes of the mountains. Water, always present, but at times terribly ruinous, earned Resia the title of the ‘wettest area in Italy’; the woods were exploited to obtain the fuel for heating, but also the raw material for the manufacture of tools, furnishings for the home and construction material.

For the ortography of the Rezian terms see the chapter n. 5; the Friulian terms are instead transcribed as they appear in the Vocabulary of the Friulian language, Faggin[14].

To indicate the plain

Rezian; ravan ‘plateau, plain’ [romïna < *ravnina, ravanza ‘plateau’, ‘small plain’]; laś ‘’cleared land’ [toponym only, martinji las]; goriza ‘’square, open space’ [diminutive of- gora]; trawnik ‘land’ [toponym only]; njïwa ‘’arable land’; poje/poe ‘’field, plain’; ladina ‘’uncultivated land’ [toponym only ]; wórtac ‘’vegetable garden’ [< wárt];

Loanwords: tarénj ‘terrain’, [tarinčeć, diminutivo], frl. <teren>; plan ‘flat surface’ [planja], frl. <plan>;

For vegetation

Rezian: gośd ‘forest’ [Pusti gośd, toponimo]; log ‘grove’ [Tu-w lóśe, toponym, locative]; ghirm ‘bush’; gharnjaš ‘bush’; rupa ‘turf’; hošća ‘dense forest’;

For reliefs and rock formations

Rezian: gora ‘mountain’; brig ‘fire’ [bréga pl.]; dul ‘gully’ [dulčeć, diminutive, tu-w dule, locative]; dolina ‘small depression’ [dolinica diminutive]; klanac ‘hillock’ [ta-pod klanzon instrumental, klinčeć’ diminutive,]; rob ‘ravine’; plaś ‘landslide, collapsed scree’; kulk ‘hill’ [Malikuk only toponym, tu-w Malikuwce, locative]; pénć/péć ‘stone’; skala ‘boulder’, [skalica, diminutive, today toponym]; kal ‘muddy ground’ [only toponym with the formant -išće> Kališće]; škraža ‘’gap in the rock or between two stones’’; pàrst ‘earth, loam’;

Loanwords: fasál ‘ditch’, frl. <fossâl>; vilinal ‘gully with debris’, frl.<lavinâl>; tòf ‘tuff’, frl. <tof>; harǧila ‘clay’, frl. <argile>;

For the use of the territory

Rezian: planina, ‘summer pasture, mountain pasture’; bardo ‘hillock’, [Gorinje bardo, toponym];

Loanwords: ronk ‘tillable terraces on a slope’, frl. <ronc>; pask ’pasture’ [paskoléč], frl. <pasc>, <pascul>, <pascoleč>; brejda ‘place name’, only toponym, frl. <braide>, long; bánt ‘land banished, reserved’, frl. <band>, from germ; malga ‘high mountain summer pasture’, frl. <malghe>;

To indicate space

Rezian: kót ‘corner angolo, cantone’; krej ‘side, limit, edge’ [ta-h kraju, dative]; kós ‘piece’; klen ‘wedge’; wárh ‘top’ [worséć, diminutive, ta-na wǎrsè, locative]; jama/ama ‘cave, quarry’, [Wúršinä amä, toponym]; skók ‘jump’; lóm ‘fracture’; konáz ‘hem, final parte‘; križ ‘cross, intersection’ [ta-par Križu, toponime], osrídek ‘which is in the centre’; sridnje ‘medium’, sedla ‘ saddle, pass’;

Loanwords: forća ‘saddle’, frl. <forčhe>; pöšt ‘place’, it <posto>; lòt ‘lot’, frl <lot>; párt ‘part’, frl <part>; ćintún ‘corner’, frl <čhanton>;

For water

Rezian: woda ‘water’ [Valïka woda ‘stream Rezia’ see photo n. 1]; potók ‘stream, brook’ [tu-w potózë locative]; vîr mirror of water, puddle, [Śaleni vîr toponym – see photo n. 2, virčeć, diminutive]; mlaka ‘source, resurgence’; prod ‘gravel bank of the river; močílo ‘moist soil with resurgences’; studenez ‘small spring’, only toponym, [tu-w Studinze, locative]; luža ‘mud’; mlïnčeć ‘whirlpool (of water)’; slap ‘waterfall’;

Loanwords: roja/róä ‘river’, frl <roi>; rojal/roáw ‘canal’, frl <rojâl>; rošta ‘little canal’, frl <roste>; päč ‘well’, frl <poč>; fontanon ‘waterfall with a continuous water flow’, frl <fontanon>; brilja ‘dam’, it <imbrigliare> [to harness]; lajp ‘tub’, frl <laip>;

On streets and boundaries

Rezian: pót, cesta ‘road, meja ‘boundary line’;

Loanwords: trój ‘path’, frl <troi>; jindrúna ‘narrow road’, frl <androne>; mulatjera ‘mule road in the mountainsi’, it <mulattiera>; konfïn ‘border’, frl <confin>; čïśa ‘hedge’, dal frl. <cise>; mažérja ‘dry stone wall’, frl <maserie>; partizjún ‘partition’, frl <partision>;

To indicate the transformation of the territory

Rezian: must ‘bridge’ [mostèć diminutive]; bärw ‘small bridge’; vas ‘village, town’; grad ‘castle’; hliw ‘stable’ [Hlivac, toponym]; mlèn ‘mill’ [Śamlèn, toponym]; gospódniza toponym [place with the remains of a building, formerly inhabited by the gospod];

Loanwords: liša ‘’channel prepared to facilitate the sliding of the logs towards the valley bain’, frl <lisse>; sadïn ‘ruins’, frl <sedim>; borg ‘village’, frl <borg>; fornáž ’furnace’, frl <fornâs>; bajta ‘hut, rifuge’, frl <baite>; štala ‘stable, frl <stale>; kazun ‘shelter for animals in the mountain’, frl <cason>; májana/máana ‘ votive chapel’, frl <maine>; čentral ‘yidroelectric power station’, it <centrale>; kobòjt ‘booth’, frl <gabiot>;

Architectural elements of house

Rezian: krèw ‘roof’; oknó ‘window’; dure ‘door’; wrata ‘door’ [only toponym]; pléna ‘roof’; powal ‘floor’; stena ‘wall’ [only toponym]; streha ‘shelter’; asla/jasla ‘trough’; slanïza ‘gutter’; dwór ‘courtyard’; bran ‘gate’; hïša ‘house’;

Loanwords: mir ‘wall’, frl <mûr>; kuvjèrt ‘roof’, frl <cuviert>; lïnda ‘balcony’ [lïndica ‘landing], frl <linde>; plančïn ‘landing’, frl <plančhe>; jntïla ‘jamb’ [v. BdC 1895, item 893]; párteh ‘arcade’, frl <puarti>; ghátar ‘trellis’, frl <gatar>; partûn ‘doorway’, frl <puarton>; škúrja ‘shutters’, frl <scûr>; ćamïn ‘chimney’, frl <čhamin>; ćavïlu ‘bolt (door), tie rod’, frl <čhavile>; kloštre ‘lock’, frl <clostri>, from germ <Kloster>; talâr ‘cornice of window’, frl <telâr>; kánkar ‘hinge’, frl <cancar>; klúka ‘handle’, frl <cluche>, from germ <Klinke>; kop ‘roof tile’, frl <cop>; laštra ’glass sheet’, frl <lastre>; padráda ‘cobbled paving’, frl <pedrade>; sćándula ‘shingle (of roof)’, frl <sčhandule>; salïš ‘paved’, frl <saliśo>; plument ‘floor’, frl <palment>; zufet ‘ceiling’, frl <sufit>; wólt ‘cross vault’, frl <volt>;

Rooms and home furnishings

Rezian: jispa ‘kitchen [arch]’, kuhinja ‘kitchen’, rem ‘room’ [arch, see Baudouin de Courtenay 1895, item 278], mïza ‘bench’; polïza ‘shelf’; korïto ‘trough’; ognjišće ‘hearth’;

Loanwords: stanzija ‘room’, frl <stanzie>; ćaniba ‘bedroom’, frl <čhamare>, [ćanibica ‘milk storage room’]; saglâr ‘sink’, frl <seglâr>; armarún ‘wardrobe, cupboard’, frl <armaron>; ćjadrèa ‘chair with armrests’, frl <čhadree>; kasalïn ‘drawer’, frl <casselin>; vitrínä ‘showcase, credenza a vetri’, frl <vitrine>; kówa ‘bed’, frl <cove>; tawla ‘table’, frl <taule>.

In the list you can see the loanwords from Romance presenters of the transformations that have penetrated the socio-economic fabric of the valley. Resians learned from their Friulian neighbours the new use of the territory (ronk, bant, pask); they acquired new indicators for the boundaries (číza, mažérja), with the probable aim of claiming ownership; they regimented the waters, often fatal, with brilja, lajp, roja, Romance terms. Even the architecture of the houses has adapted to the new living conditions, equipping itself with: linda, párteh and, to make the rooms more comfortable, with: saglâr, armarún, kasalḯn, etc. Friulanisms – Romance loanwords – have been in the Resian lexicon for a very long time, so much so that they are perceived as authentic Resian.

Germanisms

Studies on the Rezian language have not explained the reason for the many Germanisms present in the spoken language. We hope for a future in-depth and rigorous investigation, based on linguistic and phonetic data, which will clarify the chronology and origin of Germanisms – some already penetrated into the ancient Slavonic[15] – in order to outline, with the best possible reliability, the historical path of the Resians.

The condition of isolation of the valley detached it from the Slavic world, but inserted it in the Friulian administrative-political context in turn in contact with the Germanic culture and, a possible penetration into its territory by Germanic colonists, could justify the presence of part of the many loanwords.

Admitting a periodization, distinct in the early Middle Ages, the late Middle Ages and modern times, of the most ancient period, some Germanisms can be found, which Resian has in common with the Italian language[16]:

want ‘dress’ <Frank *want (gewant) >it. ‘guanto’;

warjon ‘I protect’ <Germ *warjan >it. ‘guarire;

wéra ‘war’ <Germ werra >it. ‘guerra’;

wíža ‘song’ <Germ *wīsa >it. ‘guisa’;

Wárda ‘lookout post’ M.te Guarda[17]<Gothic wardja >it. ‘guardia’;

wínća ‘curve, hairpin’ <Longobard *wankja >it. ‘guancia’;

wadánj ‘gain’ <Frank *waidhanjan >it. ‘guadagnare’;

wláćat ‘to zigzag, stagger’ <Frank *walkan >it. ‘gualcare’;

wòrćat ‘to hate, grimace’ <Gothic Þwaihrs >it. ‘guercio’;

The prospectus highlights some Rezian terms (left, in bold) deriving from Germanisms (central column), also present in the Italian language, which we identify in the right column. The barbarian invasions first and the domination of the Franks (800 AD) then left traces in both languages; but, while in Italian the Germanisms have undergone an evolution, in Rezian the words have remained unchanged in the same original form of 1000 and more years ago.

Other Germanisms present in the Rezian language are transcribed below, some of which are already present in the Old Slavonic. Also in this case Rezian is transcribed in a literary form, without distinction of the variants.

brájda ‘enclosed farm’, (now place name)’, Long <breit>; bant ‘bandit country’, <Band>; barbat ‘to paint’, <Farbe>; basat ‘to lay (a weight)’, <fassen>; beč ‘money’, MHG[18] <betz>; birmanje ‘confirmation, <Firmung>; blek ‘rag’, <Fleck>; brúman ‘willingvolonteroso’, OHG[19] <fruma>; búndar ‘vagabond’, <Wander>; bušnòt ‘to kiss’, MHG <bussen>; drukat ‘to push’, <drücken>; ejda ‘saracen corn’, <Heiden>; eršt ‘even’, <erst>; fifát ‘to smoke’, fejfa ‘pipe’, <Pfeife>; fals ‘false’, MHG<valsch>; fes ‘just’, <fest>; fléjša ‘bottl’, <Flasche>; folát ‘to make a mistake’, MHG <vālen>; frajnat ‘to be glad’, <freuen sich> [also in friulian language]; fras ‘dirty’, <Fraẞ>; frej ‘free’, <frei>; futrinat ‘to feed’, <füttern>; gater ‘grille’, OHG <gataro>; géjžla ‘whip’, MHG <geisel>; glíngeć ‘bell’, glinginját ‘to ringring’, <Klingel>; gótar ‘pal (m)’, gótra ‘pal (f)’, <*gevatter>; hákle ‘picky’, <heikel>; ghowtár ‘altar’, OHG <altāri>; híša ‘house’, OHG <hûz>; jager ‘hunter’, <Jäger>; jarmark ‘market’, <Jahrmarkt>; kambä ‘yoke’, MHG <kambe>; kartufula ‘potato’ <Kartoffel>; kétina ‘chain’ ketnica ‘small chain’, OHG <kętīna>; klanfär ‘tinsmith, lattoniere’, <Klampfen>; kloštar ‘latch’, zakloštrat ‘to close’, <Kloster>; ‘ kócä ‘blanket’, <kotze>; kolindre ‘calendar’, <Kalender>; kramär ‘ambulante’, MHG <krâmeare>; krancle ‘ghirlanda’, <Kranz>; kriklen, ‘boccale’, <Krüglein>; krimpir ‘potato’, <Grundbirne>; krükja ‘handle, duffer’, <Krücke>; kugulato ‘round’, <Kugel>; kuhat ‘to cook’, <kochen>; kǘhinja ‘kitchen’, OHG <kuchina>; kumòj ‘scarcely’, OHG <chûmo>; kuštat ‘to receive’, <kosten>; kužín ‘cousin’, <Cousin>; lata ‘bar sbarra stanga assicella’, <Latte>; léjtra ‘leiter ladder’, <Leiter>; limâr ‘always’, <immer>; lunèt ‘to reward’, OHG <lôn>; mäh ’quiet’, <gemach>; máltra ‘displeasure, dispiacere’, MHG <martre>; man ‘I must’, <man>; mitel ‘means’, <Mittel>; móšina ‘almsgiving’, OHG <alamuosan>; müneh ‘sacristan’, OHG <munih>; müs ‘necessarily, obligatory’, <müssen>; namulinat ‘to paint’, <malen>; nör ‘crazy’, <Narr>; nüna ‘godmother’, OHG <nunna>; nûr ‘once’, <nur>; ófro ‘offer’, <opfern>; okríšej ‘areal’, dal germ. <Umkreis>; ostúh ‘(neck-)tie’, <Halstuch>; pápeš ‘pope’, OHG <pâpes>; peglinat ‘to iron’, <bügeln>; pèkjat ‘to beg’, <betteln>; Pernahte ‘Epiphany’, MHG <perhnaht>; pïla ‘saw’, OHG <fila>; pöjstar ‘pillow’, <Polster>; post ‘fasting’, OHG <fasto>; pücinat ‘to rub’, <putzen>; rajtinat ‘to ride’, <reiten>; raklen ‘cane’, bav. <Rachel> (anche in friulano); rat ‘enough’, OHG <rat>; rinćina ‘earring’, MHG <rinke>; rïbež ‘grater’, ribižat ‘to grate’, <reibeisen>; rimän ‘belt’, <Riemen>; rusok ‘rucksack’, <Rucksack>; salicä ’bowl’, <Schale>; sküla ‘skab, krust’, OHG <scula>; sihǘr ‘sure’, OHG <sichūr(e)>; smarkej ‘mucus’, <schmierig>; smöla ‘resin’ <schmolz>, sowt ‘cash’, MHG <solt>; spïca ‘knitting needle’, <Spitze>; splïhat ‘to rinse (out)’, <bleichen>; stöw ‘stool’, <Sthul>; šáhte ‘business, problem, question’, MHG <geschaft>; šenk ‘gift’, MHG <schenken>; sa šïkinat ‘to co-ordinate adattarsi, coordinarsi’, <sich schicken>; šïna ‘rail’, <Schiene>; šïnfinat ‘to offend’, <schimpfen>; škarja ‘scissors’, <Schere>; škö́da ‘damage’, OHG <scado, (Schaden)>; špeh ‘lard’, <Speck>; špigle ‘mirror’, špeghat ‘to observe’, <Spiegel>; špirnjat ‘to save’, <sparen>; špugert ‘range’, <Sparherd>; šrowf ‘bolt’, <Schraube>; štíghla ‘stairs’ dal ted. <Stiege>; štokat ‘to goad’, <Stock>; štont ‘stand’, <Stand>; (sa)štráitinat ‘to peck’, OHG <strītan>; štrena ‘skein’, <Strähne>; šúštar ‘shoemaker’, <Schuster>; trofit ‘to find’, <treffen>; tróp ‘lot’, <Thorp>; tróšta ‘hope’, <Trost>; trúkat ‘to clash’, OHG <thrucken>; trúza ‘spite’, <Trotz>; túran ‘bell-toer’, <Thurm>; Vínahte ‘Christmas’, <Weihnacht>; wriden ‘worthy, deserving’, OHG <wërd>; zíat ‘to peek’, <sehen>; žbóh ‘weak’, <schwach>; žegnat ‘to bless’, <segnen>; žláhta ‘kinship’, OHG <slahta>; žleht ‘lazy’, <schlecht>; žlek ‘sleigh’, <Schlitten>; žnjidar ‘tailor’, žnjidarca ‘dressmaker’, <Schneider>; žlos ‘padlock’, <Schloss>. zïw ‘stack’, <Ziel>; zowkle ‘wooden sandal’, <Zockel>; zukar ‘sugar’, <Zucher>;

5.Ortography

To date, there is no ortography of Rezian that is shared by all.

There are various reasons for this gap, one of them is the fact that Rezians do not study their own language and literacy is taught in Italian[20].

Italian ortography is not suitable for fully representing the Rezian language due to the absence of some indispensable graphic symbols; moreover, this difficulty is also due to the scarsity of written documents which, if they had been more numerous and widespread, could have guided a participatory ortography. Finally, the absence of a shared ortography is also complicated by the presence of the variants.

For example we want to demonstrate the peculiarities of Resian, presenting the incidence of vowels in the language:

| San Giorgio | Gniva | Oseacco | Stolvizza | |

| dog | pïs | pas | päs | pes |

| more | vić | vać | već | već |

| rooster | pitilïn | pitilen | patalen | patalôn |

| cloud | woblak | öblak | öbläk | öblek |

| big | vlïk | vilék | valék | valôk |

| grape | grazdujë | hrazduje | ghrizdujë | risdujö |

| window | woknö | uknö | oknö | oknö |

| to go | jtït | tet | tet | tôt |

| country | vïs | vas | väs | ves |

| lunch | wobët | ubëd | obët | obët |

To know the particularity and variants of the Resian language it is of great help to read the text of Baudouin de Courtenay Opyt fonetiki res’janskich govorov, Warsaw – Peterburg 1875 and in particular, the paragraphs from number 284 to 289.

Special symbols used in this article to transcribe Rezian.

| Graphic

symbol |

pronunciation | International phonetic alphabet |

| č | like ‘church’in English | voiceless Postalveolar affricate ʧ |

| ć | voiceless palatal occlusiv c | |

| ǧ | Like ‘just’ in English | voiced postalveolar affricate ʤ |

| ǵ | Similar to Scottish ‘jar’ | voiced palatal occlusiv ɟ |

| gh | Like the Spanish ‘trigo’ | voiced velar fricative ɣ |

| nj | Similar to ‘nuisance’ in English | nasal palatal ɲ |

| š | Like ‘shoe’ in English | Voiceless postalveolar fricative ʃ |

| ś | like ‘rose’ in English | Voiceless postalveolar fricative z |

| w | like ‘witch’ in English | voiced labio-velar approximant w |

| z | voiceless alveolar affricate ʦ | |

| ž | like ‘television’ in English | Voiced postalveolar fricative ʒ |

| ä | cupped | |

| For the following voweles reference is made to the explanations of BdC, quoted work § 13 | ||

| ë | With the median opening between the positions of the oral cavity for e and that for o, but closer to the position for e than that for o with the opening of approximately German o̎ or French eu | |

| ö | As the French eu | |

| ï | As the Russian ы | With the opening of the vowel i, obtained by approaching the back of the tongue and the palate, or by opening the Russian ы |

| ü | As the German ‘über’ | With the opening of the German ü or, more precisely, the French u |

AD Anno Domini

arch archaism

f, fem feminine

Germ German

lit literally

Longob Longobard

ma masculine

MHG Medium High German

OHG Old High German

Baudouin de Courtenay, 1875a: Opyt fonetiki rez’janskich govorov. Warsaw – Peterburg;

Baudouin de Courtenay, Saggio di fonetica delle parlate resiane a cura di N. Clemente, Udine 2018;

Baudouin de Courtenay, Resia e i Resiani, a cura di Madotto e Paletti, Resia 2000;

Baudouin de Courtenay 1875b: Rez’janskij Katichizis, kak priloženie k “Opytu fonetiki rez’janskich govorov” Varšava-Peterburg;

Baudouin de Courtenay 1895: Materialen zur südslavischen Dialektologie und Ethnographie I: Resianische Texte, St. Petersburg, 1895;

Baudouin de Courtenay, a cura di, Materialen zur südslavischen Dialektologie und Ethnographie III: Resianisches Sprachdenkmal “Christjanske Uzhilo”, St. Petersburg 1913;

Borriero Lavinia Grammatica bulgara Firenze, 1982

Chinese Sergio, Rośajanskë- Laškë Bysidnjäk, Repertorio lessicale italiano – resiano, Udine 2003;

Chinese Sergio, Il Vangelo – Uänǵëlë pu rośajanskë, Udine 2013;

Clemente Nadia, Introduzione alla lingua resiana, Udine 2020

Dapit Roberto, 1995, Aspetti di cultura resiana nei nomi di luogo, 1. Stolvizza e Coritis, Gemona del Friuli;

Dapit Roberto, 1998, Aspetti di cultura resiana nei nomi di luogo, 2. Oseacco e Uccea, Gemona del Friuli;

Dapit Roberto, 2008, Aspetti di cultura resiana nei nomi di luogo, 3. San Giorgio, Gniva e Prato, Gemona del Friuli;

Holzer Georg, Gli Slavi prima del loro arrivo in occidente, in Lo spazio letterario del Medioevo, 3 Le culture circostanti, 2006:23;

Longhino Arturo Arketow, 1978 Resia, Ella von Schultz-Adaiewsky, Canti e danze popolari della Val Resia, Testi raccolti negli anni 1883 e 1887;

Longhino Arturo 1979a, Arketöw, Catechismo resiano, come appendice al “Saggio di fonetica delle parlate resiane”, edito da Jan Baudouin de Courtenay, Varsavia-Pietroburgo 1875;

Longhino Arturo Arketöw, 1979b Sull’Armonia vocalica dei Dialetti resiani di Jan Baudouin de Courtenay, estratto da Atti del IV Congresso internazionale degli orientalisti, Firenze 1881;

Longhino Arturo Arketöw, 1979c, Ella von Schultz-Adaiewsky La Ninna Nanna Popolare;

Longhino Arturo Arketöw, 1980 Rozajanske Induvynke – Indovinelli resiani;

Longhino Arturo Arketöw, 1981, Sull’appartenenza linguistica ed etnografica degli Slavi del Friuli, di Jan Baudouin de Courtenay, estratto da XI Centenario di Paolo Diacono, Cividale 1899;

Longhino Arturo Arketöw, 1983, Christjanske Uzhilo, da Materialen vol. III, di Jan Baudouin de Courtenay, Sainkt-Peterburg 1913;

Longhino Arturo Arketöw, 1984a Resia-Grassau, Il Catechismo Resiano, estratto dal Materialen vol. I, 1891;

Longhino Arturo Arketöw, 1984b Resia-Grassau, Raccolta di Pater noster resiani;

Longhino Arturo Arketöw, 1984c Resia-Grassau, Jan Potocki 1761-1815, Brevi cenni sui resiani,

Marcialis N. Introduzione alla lingua paleoslava, Firenze 2007;

Pul’kina I., Zachava-Nekrasova E. Il Russo, Grammatica pratica con esercizi, Mosca 1989

von Schultz Adaïewsky Ella, Un voyage à Rèsia, a cura di Febo Guizzi, Lucca 2012

Sreznevskij Izmail I., Gli Slavi del Friuli: Resiani e Sloviny, SanktPeterburgъ, 1878;

Sreznevskij Izmail I., Матерялы для Древно-русскаго языка – Materiali dlja Drevno-russkago jazyka, SanktPeterburg’, 1893;

Bajec-Kalan, Italijansko-slovenski slovar, Vocabolario italiano-sloveno, Ljubljana 1971;

Janko Kotnik, Slovensko-italijanski slovar Vocabolario sloveno-italiano, Ljubljana 1981;

- M. Cejtlin, R. Večerki, E. Blagovoj, Старославянский словарь (по рукописям X – XI веков), R. M. Cejtlin, R. Večerki, E. Blagovoj, Москва 1994;

- I. Tolstoj, a cura di, Резьянский Словарь di Baudouin de Courtenay, Moskwa 1966:183-226;

Vocabolario della lingua friulana, Faggin Giorgio, Udine 1985;

Vocabolario della lingua italiana, N. Zingarelli;

Vocabolario della lingua tedesca, Tedesco, Garzanti linguistica, Varese 2015;

Anyone wishing to know Resia and the Resians better can consult the writings of Baudouin de Courtenay, also available online:

1) Opyt fonetiki res’janskich govorov. Warsaw – Peterburg 1875;

http://books.e-heritage.ru/book/10075815

2) Rez’janskij Katichizis, kak priloženie k “Opytu fonetiki rez’janskich govorov” Varšava-Peterburg 1875; http://books.e-heritage.ru/book/10075815

3) Materialen zur südslavischen Dialektologie und Ethnographie I: Resianische Texte, St. Petersburg 1895; http://books.e-heritage.ru/book/10075812

4) Materialen zur südslavischen Dialektologie und Ethnographie III: Resianisches Sprachdenkmal “Christjanske Uzhilo”, St. Petersburg 1913; https://www.dropbox.com/s/y7zx7mx94a0xb1d/BdC%2C%20Mat.%20III%2C%201913%20–%20Christjanske%20uzhilo.pdf?dl=0

5) Rez’janskij Slovar’ (pod redakzijej N. I. Tolstova) 1 in Slavjanskaja Leksikografija i Leksikologija, 1966, pp. 183-226; http://inslav.ru/images/stories/pdf/1966_leksikografija_i_leksikologija.pdf

[1] See http://www.cuf-ancun.it/lingue-minoritarie/resia/

[2] La Porta d’Italia – Diaries and Polish travellers in Friuli-Venezia from the 16th to the 19th century, edited by Lucia Burello and Andrzej Litwornia, Udine 2000: 362 “At the twenty-first kilometre from the border we had crossed, is the Resiutta railway. Next to this, in the mountains a few kilometers to the East, as my very kind travel companion Fr Luigi Costantini, apostolic missionary, told me in December 1887, there are three places not far from each other called Resia. They are inhabited by the Slavs who arrived in these parts as early as the fifth century of the Christian era from Ruthenia. ” From the diary of Wincenty Smoczyński – Wspomnienia o Polskiéj pielgrzymce do Rzymu w roku 1888 na Jubileusz J. S. Leona XIII Papieža. 225-226, 746-748.

[3] W. Breu, M. Pila, L. Sholze Видовые приставки в языковом контакте (на материале молизско-славянского, резьянского и верхнелужицкого микроязыков) Biblioteca di Studi Slavistici n.39, 2017:61.

[4] Vittorio Coletti L’italiano scomparso. La grammatica della lingua che non c’è più, (Il Mulino, 2018)

[5] See at the bottom of my article.

[6] Старославянский словарь (по рукописям X – XI веков), R. M. Cejtlin, R. Večerki, E. Blagovoj, Москва, 1994;

[7] Holzer Georg, Gli Slavi prima del loro arrivo in occidente, in Lo spazio letterario del Medioevo, 3 Le culture circostanti, 2006:23;

[8] see Baudouin de Courtenay Опыт фонетики резьянских говоров, Warsaw – Peterburg 1875, §173;

[9]In Resian ‘o’ and ‘u’ are interchangeable in certain positions, we can also say ëru / jeru.

[10] I. I. Sreznevskij, Фріульскіе Славяне , Санктпетербургъ, 1878:12, note n. 3;

[11] I. I. Sreznevskij, Матерялы для Древно-русскаго языка – Том второй, 1893:8;

[12] the term ‘rede [= row’, with a value of ’10’] suggests a mathematical calculation based on the use of the abacus.

[13] Vocabolario della lingua latina ‘Castiglioni-Mariotti’, Loescher, 1990:998;

[14] Vocabolario della lingua friulana – Del Bianco, 1985;

[15] hïša ‘house’, AAT <hûz>; jispa ‘kitchen’, *jьstъba; zirkuw ‘church’, *kirikō.

[16] The comparison was made by consulting the Vocabulary: Vocabolario della lingua italiana 1983, N. Zingarelli

[17] Monte Guarda (lett. ‘it looks) from where to observe and control the surrounding territories, already during the Lombard era.

[18] MHG: Medium Hig German;

[19] OHG: Old Hig German;

[20] Nowadays primary school pupils do 45 hours year of Resian language.