Seasons in Opole / Oppeln: An Elgin Marbles Case?

Tomasz Kamusella

University of St Andrews

Flood Uncovers the Past

In 1997 the gigantic flood across the draining basin of the Oder (Odra) hit central Europe. It was the turning point that shook out of stupor many municipalities across postcommunist Poland. Especially, in the western half of this country, which used to be part of Germany prior to 1945. Until that moment the Polish authorities had been wary of the prewar past that was so un-Polish. For ideological reasons, the adjectives ‘German’ or ‘Prussian’ were avoided, because communist Poland’s propaganda justified the incorporation of these German lands east of the Oder-Neisse line (or the deutsche Ostgebiete in German) by claiming that they were ‘ur-Polish, eternally Polish.’

The large-scale reconstruction, renovation and beautification of numerous towns and cities across western Poland allowed their inhabitants to reconnect with the German and Prussian past. Instead of plastering over, sawing off, or chiseling out inscriptions, symbols and decorations that would be seen as a sure sign of unacceptable Germanness in communist Poland, now such architectonic and urbanistic elements were reinvented as ‘European.’ Many were even openly declared to be of ‘all-European’ importance. The process of Polish-German reconciliation – commenced by Chancellor Helmut Kohl ‘the Re-unifier’ and the first postcommunist Polish Prime Minister Tadeusz Mazowiecki – did help.

The increasing acceptance of the pre-1945 past, architecture and culture of western Poland by its contemporary post-1945 inhabitants was also facilitated by the re-discovery of the formerly suppressed Polish past in the east, or in present-day Belarus, Latvia, Lithuania and Ukraine. As Germany lost its eastern territories to Poland (and to the Soviet Union), interwar Poland did lose its own eastern lands (or the so-called Kresy ‘borderlands’) to the Soviet Union. Now these former Polish areas are included in the aforementioned four post-Soviet states.

(Source: http://retropress.pl/tag/ziemie-odzyskane/)

An Uneasy Allure of Germanness

Yet, the open-minded embracement of the prewar past has been more difficult in Opole Region (województwo opolskie). This area belonged to Germany and the Land of Prussia before 1945. In the other German territories granted to Poland, their populaces, classified as ‘Germans,’ were expelled westward, across the Oder-Neisse line, to post-1945 Germany. However, in Opole Region the majority of the prewar inhabitants of Opole Region were retained. The communist authorities claimed them to be as ‘ur-Polish’ as the German territories just incorporated into postwar Poland.

Communist totalitarianism came to an end in 1989. Under democracy the Polish authorities lost the possibility of imposing the ideological vision of eternal Polishness on unwilling communities. At long last Opole Region’s ‘ur-Poles’ (or Autochthones, autochtoni, as the official term was in communist Poland) were free to decide about their identity on their own. Unsurprisingly, after half of a century of humiliations suffered in communist Poland, most settled for Germanness. Nowadays, Germans constitute a third of Opole Region’s inhabitants, but the ethnically Polish elite retains tight control over the governance and culture of the entire region. Germans are allowed a limited freedom of local government in these communes, towns and counties, where they add up to the majority or plurality of the inhabitants.

As a result, the German and Prussian past of Opole Region is neither denied, nor cherished. In the wake of the 1997 flood, the Lower Silesian capital of Wrocław (Breslau) was rebuilt with an eye to recovering its German architectonic and cultural past. On the contrary, the city of Opole (Oppeln) decided to beautify itself with a generic architectonic past of a vaguely central European provenance. The clear goal has been to belittle or marginalize any remaining German or Prussian traces. This is a symptom of willing or unconscious attachment to the national-communist policy of ‘de-Germanization’ (odniemczanie), pursued after World War II for the sake of ‘re-Polonizing’ (repolonizacja) Autochthons and for tearing down the ‘German façade.’

The German-language text was chiseled out from the pre-1945 gravestone, Gliwice (Gleiwitz) – fot. Pudelek (Marcin Szala) / CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Instead of producing ‘pure’ Poles, this ‘re-Polonization’ convinced even pro-Polish Autochthons that for them it would make more sense to remain Germans. On the other hand, it soon turned out that medieval archeological remains recovered from underneath the successfully removed German façade were not of the caliber desired by the region’s ambitious authorities. It was a cruel dilemma how to choose between the cultural riches of the Prusso-German past and the near-void of the Slavo-Polish medieval period.

Opole’s Elgin Marbles

Apart from the Old Town, another high point of Opole’s post-1997 reconstruction-cum-reinvention is the University Hill (Wzgórze Uniwersyteckie). The region obtained its first-ever university in 1994. At that time Opole University (Uniwersytet Opolski) had a unique chance to become Poland’s first-ever bilingual (Polish-German) university that would cater for the educational needs of all the region’s inhabitants, both Poles and Germans. But this opportunity failed to materialize. Communist Poland’s self-limiting policy of never-ending Polonization won the day in the postcommunist Opole Region. Tellingly, the university’s website is available in English and Russian, alongside Polish, but not in German.[1] (The Russian-language version is intended for Ukrainian students, which in itself is offensive, given that Russia has been waging war on Ukraine since 2014.)

(Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wzgórze_Uniwersyteckie_-_panoramio_-_romstar_(2).jpg)

The University Hill is branded as a ‘place for visionaries,’ who look forward to the future.[2] Unfortunately, the future appears as ‘synthetic’ and unrelated to the region’s past, as the manner in which the city was rebuilt after the 1997 flood. In addition, the alluded ‘future’ appears to be none other than selected cultural highlights of the Polish Opole from the communist period. Indeed, back to the future. In front of the university’s main building, or the Collegium Maius,[3] a welcoming group of human-size bronze figures sprang up during the last two decades. They depict legendary Polish singers and cabaret artists who gained fame during the communist years. Only the monument of the theater director and theorist, Jerzy Grotowski, is devoted to a personality of an international stature.[4] Grotowski began his career in Opole, where he created and ran the famous avant-garde Teatr 13 Rzędów (Theatre of 13 Rows) between 1958 and 1965.[5] Other celebrities depicted in the form of bronze figures[6] are connected to Opole just tangentially, thanks to the Krajowy Festiwal Piosenki Polskiej (National Festival of the Polish Song) that has taken place in Opole annually since 1963.[7]

Tellingly, not a single bronze figure has been devoted to any prewar actor, director, artist, singer or poet. Such a personality, if ever considered for such an elevated role, obviously used to talk and write in German. Hence, present-day Opole’s predominantly Polish, from the ethnic perspective, inhabitants would see her or him as ‘unacceptably’ German. The Polonization of this city and region has not been completed yet, even though the local Germans do not speak any German as a community, and usually live outside Opole. Irrespectively, Polonization continues and appears to be the main – though rarely expressed explicitly – axiom of the city’s developmental strategy for any foreseeable future.

On the other side of the University Hill, more hidden from sight, a Polonizing union with the region’s pre-1945 past has been attempted in a curiously colonial manner. In the 1990s, Rektor (University President) of Opole University, Stanisław Nicieja, combed Opole Region in search of neglected and abandoned sculptures and elements of funerary architecture. He gathered these at his own home, apparently without informing the local authorities or the owners of the buildings or plots of land from which such historic object were ‘harvested.’ This activity was in contravention of the laws on historical monuments and ownership. Hence, eventually Rektor Nicieja was compelled to return most of the gathered objects to the locations from where he had taken them.[8] However, in 2001 he gained a mandate to the Polish Senate, which gave him an upper hand in the power game. The regional authorities had no choice but to demure[9] to now Senator Nicieja’s wishes and courteous explanation that without his timely intervention most of the historical objects would have perished through neglect and exposure to elements.[10]

(Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Elgin_Marbles_British_Museum.jpg)

As a result, the communist-period approach to the region’s pre-1945 German and Prussian heritage continues unabated to this day. In communist Poland this heritage was seen as shameful, and most of it was actively destroyed or allowed to go to waste as part and parcel of the ‘de-Germanization struggle’ against the persisting ‘German façade.’ At present, the heritage is appreciated but often treated as ‘ownerless.’ Hence, any person in power, like Senator Nicieja, may embark on a weekend ‘expedition’ to a ruined park or palace, and help themselves to what they like. Not unlike British imperialists with a taste for the classical beauty of ancient Greece. For instance, between 1801 and 1812, Earl of Elgin, Thomas Bruce, removed the stunningly beautiful marble sculptures from the temple of the Parthenon on the Acropolis in the then Ottoman town of Athens. Subsequently, he gifted the looted sculptures to the British Museum. Under the name of ‘Elgin Marbles’ they constitute one of the institution’s most prized highlights. Unsurprisingly, modern Greece sees what happened as a theft, a prime case of heritage crime.[11]

(Source: https://polska-org.pl/878994,foto.html?idEntity=511708)

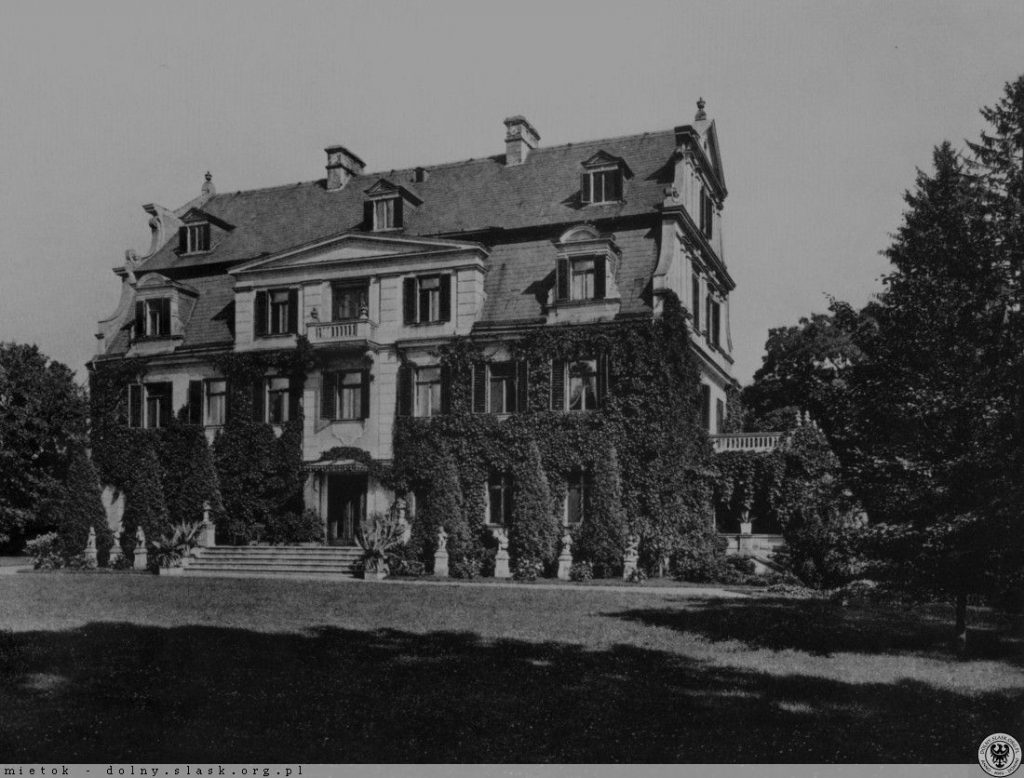

In 2003 Senator Nicieja founded Opole University’s Association for Saving Opole Region’s Heritage (Uniwersyteckie Stowarzyszenie na rzecz Ratowania Zabytków Śląska Opolskiego)[12] in order to give such neocolonial in their character activities a sheen of respectability. The task completed, this NGO was dissolved in 2019.[13] They had a real scoop in the village of Biestrzykowice (Eckersdorf), located in the region’s northwestern corner.[14] Unlike in the center and east of Opole Region, where Autochthons-cum-Germans live, all the indigenous inhabitants were expelled from the region’s western section, including the aforementioned village. The local administration had no problem that members of this above-mentioned Association loitered around and kept removing historical objects from Biestrzykowice and the vicinity. The village’s ethnically Polish authorities and inhabitants mostly see little value in the pre-1945 heritage. It has no direct historic, ethnic or personal meaning for them, because they settled here after World War II. Anyway, the action of removing pre-selected historic objects was sanctioned by Senator Nicieja himself, so all must have been in order from the legal point of view. Old customs inherited from the period of communist totalitarianism die hard: the powers that be are always right.

(Source: http://www.polskiezabytki.pl/m/obiekt/4061/Biestrzykowice/)

In a 2003 interview, Senator Nicieja readily admitted that he was overjoyed with this scoop in Biestrzykowice, because ‘until this moment, [the city of] Opole did not have monuments of such great artistic and historical value’ (Opole nie miało do tej pory tej klasy zabytków[15]). It could be noted though that numerous precious monuments of this type the city of Opole had lost to warfare before 1945 and later to the officially sanctioned policy of struggling against the German façade (that is, de-Germanization). Senator and his Association’s scoop was a rare complete group of rococo sculptures of four seasons. Duly renovated, in 2004 the group was re-erected at the quiet and secluded end of the University Hill, safely hidden from a prying or jealous eye. These sculptures are a work of the 18th-century local sculptor, Heinrich Hartmann, from Bardo (Wartha) in nearby Lower Silesia.[16] Originally, in 1752, the four sculptures were installed in the park of the Eckersdorf (Biestrzykowice) palace,[17] then in the hands of the Falkenbergs.[18]

(Source: https://polska-org.pl/866064,foto.html?idEntity=511708)

Curiously, the names of the seasons at the pedestals of these four female figures in sandstone are given in Polish as Wiosna (Spring), Lato (Summer), Jesień (Fall) and Zima (Winter). In Prussia, the elite spoke and wrote in German and French. A decade earlier, in 1740-1742, the Prussian King had wrenched Silesia away from the Habsburgs. In the Habsburg lands Latin remained the official language until 1784. Hence, from the historical and heritage perspective the names of seasons should be given in German (Frühling, Sommer, Herbst and Winter), or at least in Latin (Ver, Aestas, Autumnus and Hiems). Supplying these names in Polish is a blatant anachronism, breaches the principles of renovation, and amounts to a willful act of falsification. Yet, in the postwar context of Opole Region this decision fits the long-established pattern of the policy of de-Germanization.

Perhaps, as an afterthought, a commemorative stone was added for the sake of enlightening a curious visitor on the history of the four stunning sculptures. In accordance with the consciously or unconsciously espoused Polish national dogma of de-Germanization, the stone’s inscription is done entirely in the Polish language. Only the title of the group of sculptures, ‘The Four Seasons,’ is given in Polish (Cztery Pory Roku) and in German. However, the German-language title, Jahreszieten, is misspelt, and should read Jahreszeiten. It is a clear sign of disrespect to any German-speaker, or for that matter, to descendants of this sculptor and his patrons, the Falkenbergs of Eckersdorf (Biestrzykowice). They would immediately spot this spelling error. Furthermore, out of the inscription’s 45 words, seven are devoted to the sculptor, a mere one to the provenance, nine to the wartime damage, and as many as 28 to Senator Nicieja and Opole University’s Association for Saving Opole Region’s Heritage. Not a single word was spent on the Falkenbergs who commissioned the sculptures, or on the subsequent owners of the Eckersdorf (Biestrzykowice) palace who took care of the objet d’art in the palace’s garden.

On top of that the palatable contempt for all things German is discernible from the ‘translation’ of the sculptor’s German-language first name ‘Heinrich’ to the more familiar Polish version of ‘Henryk.’ How would Senator Niciej feel if his own first name ‘Stanisław’ was translated into German as ‘Stanislaus’? I am sure he would be appalled by such an unwarranted incursion against his own personal rights. And what about Opole Region’s Germans? All the situation amounts to an umpteenth example of customized condescension and contempt for the German minority, as practiced by the region’s authorities and the Polish ethnic majority, obviously in line with the dogma of eternal de-Germanization.

(Source: http://straznicyczasu.pl/viewtopic.php?t=14204&p=39003)

(Source: http://straznicyczasu.pl/viewtopic.php?t=14204&p=39003)

In the western Ukrainian metropolis of Lviv (Lwów), the 19th-century monument to the Polish national poet, Adam Mickiewicz, towers proudly over the city center. The Polish name of this poet, done in Latin letters, stands out in the sea of the Ukrainian Cyrillic. Senator Nicieja does know about this fact, because he is Poland’s foremost specialist in the cultural history of the Kresy, or the eastern half of interwar Poland, now located in Belarus, Latvia, Lithuania and Ukraine. How would he and his colleagues from the Association feel, should the Lviv (Lwów) municipality decide to ‘translate’ this monument’s inscription to the more familiar Cyrillic-based Ukrainian version of Адам Міцкевич? I am sure all of them would take offense and protest loudly at such an outrage.

(Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ukraine-Lviv-Monument_to_Adam_Mickiewicz-2.jpg)

Yet, disparaging the Prusso-German past of Opole Region, contempt for German language and culture, alongside studious disrespect for the region’s Germans continue to be the traditional norm in Opole. No one is surprised. The now eight-decade-old campaign of Polonization, euphemistically known as the policy of ‘de-Germanization,’ has borne rich fruit. The local Germans have thoroughly acquiesced to their fate, if they want to continue living in their Heimat (homeland). At the same time, the region’s ethnically Polish authorities and inhabitants do not think twice that their decisions may hurt the feelings of their German neighbors. The situation is not seen as inappropriate, let alone as an outrage.

New Synagogue in Oppeln (Opole) in 1930

New Synagogue in Oppeln (Opole) in 1930

(Source: https://www.jüdische-gemeinden.de/index.php/gemeinden/m-o/1528-oppeln-oberschlesien)

Hence, pre-1945 historical objects can be still looted and de-Germanized for the colonial-style re-use in the region’s Polish capital city of Opole. Within the scope of this abuse of the region’s prewar Prusso-German heritage, an unnoticed absence lurks that unfortunately agrees with the wishes of both Poles and Germans in Opole Region. Curiously, among the historical objects collected by Senator Nicieja, and subsequently repossessed by his Association for the beautification of the University Hill, none appears to be of a Jewish provenance. However, numerous synagogues and Jewish communities existed in Opole and the region before the war.[19] So equally numerous Jewish historical objects should be readily available for ‘harvesting.’ It seems that an inscription in Hebrew letters would be even a greater anathema to Opole’s Polish-speaking Catholics than an obviously German monument…

July 2020

[2] https://uni.opole.pl/page/2248/wzgorze-uniwersyteckie-miejsce-wizjonerow

[3] https://www.uni.opole.pl/en/page/835/virtual-tour-of-collegium-maius

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jerzy_Grotowski

[5] https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Teatr_13_Rzędów_w_Opolu

[6] https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pomnik_Agnieszki_Osieckiej_w_Opolu

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Festival_of_Polish_Song_in_Opole

[8] https://archiwum.rp.pl/artykul/266433-Grzechy-rektora-Niciei.html

[9] https://opole.wyborcza.pl/opole/1,35086,2116616.html

[10] https://forumakademickie.pl/fa-archiwum/archiwum/99/7-8/artykuly/dziecko_sczescia.htm

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elgin_Marbles

[12] http://www.zabytki.uni.opole.pl/index.php?id=zarzad

[13] https://rejestr.io/krs/150599/uniwersyteckie-stowarzyszenie-na-rzecz-ratowania-zabytkow-slaska-opolskiego

[14] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biestrzykowice

[15] https://nto.pl/piekna-ta-zima/ar/3977365

[16] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bardo,_Poland

[17] https://polska-org.pl/511708,Biestrzykowice,Palac_Biestrzykowice.html

[18] https://50ok.pl/cztery-pory-roku-cudowne-rzezby-niedaleko-uniwersytetu-opolskiego/

[19] Cf https://www.jüdische-gemeinden.de/index.php/gemeinden/m-o/1528-oppeln-oberschlesien