Judeo-Christian Europe and Language Politics

Tomasz Kamusella

University of St Andrews

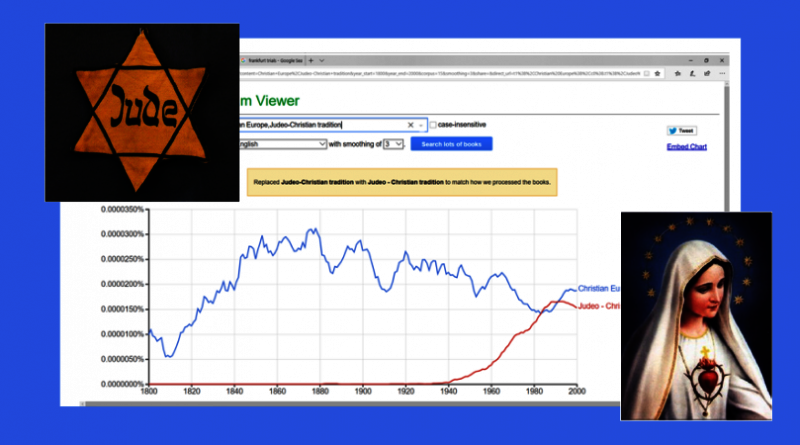

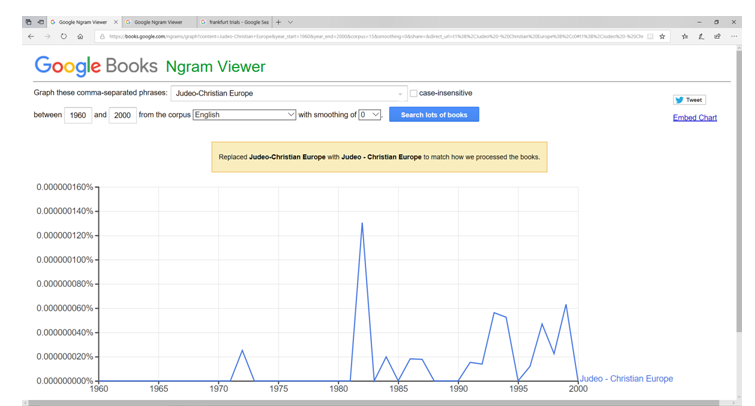

During World War II, the phrase ‘Judeo-Christian tradition’ was adopted as the main – initially, Anglo-American – concept for defining the moral and philosophical foundation of the western civilization, then at loggerheads with the Soviet Union and the Third Reich.[1] At the same time, this phrase, due to the official endorsement,[2] became more popular than its interwar ideological competitors, namely, ‘Soviet values,’ or the anti-Semitic stereotype of ‘Judeo-Bolshevia.’[3] This divergence in the overall popularity of these three phrases widened in the early 1960s, and became truly pronounced in the 1980s. The two rapid increases in the use of the collocation ‘Judeo-Christian tradition’ correlate well, respectively, with the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials and the last Cold War standoff between the two superpowers. The former spike marked the beginning of the universally accepted recognition and condemnation of the Jewish Holocaust, while the latter heralded the fall of communism and the Soviet bloc. What is more, the 1980s also saw the acceleration of the process of European integration, which encouraged the emergence of the novel term ‘Judeo-Christian Europe.’[4] The phrase ‘Christian Europe’ as the expression of the West’s ‘civilizational supremacy’ peaked between the mid-19th and mid-20th centuries. Subsequently, the supremacist character of this ideology was moderated with the post-Holocaust adoption of the concept ‘Judeo-Christian tradition.’ The frequency of the use of both became equal in the aforementioned crucial decade of the 1980s. (Although to this day, the overall use of the term ‘Christian Europe’ dwarves the employment of the collocation ‘Jewish Europe,’[5] the latter is on a par and in a clear competition with the concept of ‘Islamic Europe.’[6])

In the process of building united Europe, the expression ‘Judeo-Christian roots of Europe’ got much more traction in public discourse during the mid-20th century than its less geographically specific counterpart ‘Judeo-Christian tradition.’[7] In the early 1980s, the synonymous collocation ‘Christian roots of Europe’ suddenly sprang into the fore, but failed to replace the by then well-established phrase ‘Judeo-Christian roots of Europe.’[8] The rise of this phrase’s German-language counterpart, judeo-christliche Wurzeln Europas,[9] was even more rapid in the 1980s, while the German expression christliche Wurzeln Europas (‘Christian roots of Europe’) apparently failed to coalesce as a set phrase of public discourse. Interestingly, in the German compound adjective judeo-christlische it is possible to reverse the order of its two constituents, resulting in the form christlich-jüdische. The latter form clearly predominated until the turn of the 20th century, when both forms reached a parity in use.[10]

In 1955, the Council of Europe adopted the blue European flag with the circle composed of the 12 five-pointed yellow stars. Later, it became the flag and the main symbol (logo) of the European Union. Some commentators point to the unacknowledged Christian origin of this flag, namely, the Catholic canonical depiction of the Virgin Mary with the aureole of 12 golden (that is, yellow) stars. On the other hand, during the Second World War, in German-occupied Europe the yellow star was used for branding Jews and excluding them from society. Nazis employed the six-pointed Star of David for this purpose. The difference of one point is tiny and scholastic to say the least, given that the stars depicted in the Virgin Mary’s aureole differed – at times quite widely – in their number of points from painting to painting, and from sculpture to sculpture. Hence, the European flag aptly reflects the Judeo-Christian origin and values of the European Union.

The problem is that while Christian traditions, values and histories are cherished and cultivated in today’s Europe, the same cannot be really said of their Jewish counterparts. The prominent initial ‘Judeo’ half of the term ‘Judeo-Christian tradition’ is pronouncedly absent from everyday practices in the member states of the European Union. Yes, there is no Jewish state in Europe, and after the Holocaust not a single European polity houses a considerable Jewish community. This is so, despite the fact that until the war, the majority of the world’s Jews lived in Europe, or more exactly in central Europe, which nowadays overlaps with the eastern half of the European Union. In Poland Jews used to constitute a tenth of the population prior to World War II. At the beginning of the 21st century, the largely unrealized remembrance of the exterminated Jews yielded the ubiquitous neo-folk, or folk-like (and somewhat anti-Semitic), image of a middle-aged bearded Hassidic Jew with a gold coin in his hand. In today’s Poland many have paintings and sculptures of the ‘Jew with a coin’ (Żyd z pieniążkiem) on display in their living rooms as a talisman of prosperity and good luck.[11] Unfortunately, manifold more ‘Jews with a coin’ populate the country than living Jews themselves.

Although the (Yiddish-speaking) Jews (Ashkenazim) were a par excellence (central) European (ethnolinguistic) nation before the mid-20th century, nowadays their ideologically and culturally European (and ethnolinguistic) nation-state of Israel is located in the postcolonial Middle East. What remains in the Ashkenazim’s millennium-old homeland of Yiddishland is mass graves, frequently unacknowledged Jewish buildings and monuments, alongside increasingly more numerous monuments and museums of the Holocaust. In the present-day Europe, where the membership of the Churches of various Christian denominations is on the precipitous wane, alongside the observance of traditional religious practices (prayer or the mass), the moral message of the Ten Commandments rings hollow. In this context, the aforementioned Holocaust museums and monuments provide the much needed, and universally comprehended and accepted moral dimension in today’s Europe, namely, ‘Thou shalt not kill.’ This is the lowest common denominator of modern Europe’s morality. Perhaps, sticking to this principle in the era of weapons of mass destruction in human hands is of more importance than ever before. Industrialized killing wipes out peoples, while nuclear warfare shall doom the entire humanity. Nuclear death does not discern between religions, languages, cultures or nations.

Therefore, this hard-working crucial word ‘Judeo’ in the phrase ‘Judeo-Christian roots of Europe’ walks the proverbial extra mile in order to keep reminding Europeans that the project of European integration and of the European Union is above all about peace, the prevention of any new genocide, or the ultimate self-destruction of the humanity. The fate of Europe’s Jews, the Holocaust, is the constant ethical reminder for us all – irrespective of worldview, language, faith, social status, or espoused values – not to veer ever again from the narrow righteous path of ‘Thou shalt not kill.’ This message is rarely lost on the ears of Europeans, since no party or movement with the program of a genocide on its flag has made it to the parliament of any European state after the Second World War.

What saddens and surprises is that the oft-lauded and repeated Jewish basis of Europe’s Judeo-Christian tradition does not translate into even a modest acknowledgement for the Jews and their invaluable contribution to Europeanism. With the departure of the last Holocaust survivors and their gentile peers, who witnessed this genocide perpetrated by wartime Germany (including Austria) and its allies, this unacknowledged edifice of Europe’s secular morality trembles and may collapse with dire consequences for the continent. The urgent question is how to revive the working active remembrance of the Holocaust without the now almost unavailable privilege of living eyewitnesses. The multiplication of monuments and museums is a short-term stop-gap. What if future generations of Europeans of the 2020s and 2030s will begin observing them neutrally (as we now glance now at ancient Egyptian sepulchers in a museum), and thus cease to draw any moral meaning from such symbolical and documentary remembrance of the Holocaust?

I believe the solution to this urgent dilemma is simple. The role of Jews in the development, transition and maintenance of the Judeo foundation of the Judeo Christian tradition must be fully and unequivocally acknowledged. Europe’s Judeo-Christian roots have safely grown and spread in the soil of the ‘Judeo’ thought and ethics, ensuring stability, security and prosperity for the entire continent. Such acknowledgement may be achieved in numerous ways. The best one would be the revival of Yiddishland at the heart of Europe, from France to Ukraine, and from Scandinavia to the Balkans. However, this possibility may not be on the cards anytime soon, given the preference of today’s Jews for Israel and the United States. At present, not a single European locality, let alone region, enjoys a Jewish plurality of the inhabitants.

The Hebrew script of the Jewish languages of Hebrew, Spanyol (Ladino, Judeo-Spanish), or Yiddish (‘Judeo-German’) has been part and parcel of common European heritage until the rise of politicized anti-Semitism in the second half of the 19th century. In 1846, the use of Hebrew letters for any official purposes was banned across the Austrian Empire (known as Austria-Hungary after 1867). Prussia and the Russian Empire followed suit in 1847 and 1862, respectively. This new restrictive practice of official and cultural anti-Semitism was extended across the German Empire, which was established in 1871. Yiddishland and its culture were effectively contained to Jewish communities and households. A socio-political ghetto of disapproval for Jewish culture was erected. A Jew was not permitted to send a letter in an envelope addressed in Hebrew letters to a family member or commercial associate. A post office clerk would deride and turn away a bearded Hassid attempting to send a telegram written in the Hebrew script. And absolutely no documents in this script would be accepted by state offices, while civil servants would not write or endorse any documents done in Hebrew letters. The public space of European culture, state administration, commerce, or communication became Judenrein (‘cleansed of Jews’) a whole century before the Holocaust.

Nowadays, almost a century after the Holocaust, Europe is still in the same discriminatory Judenfrei (‘free of Jews’) rut. In a manner unprecedented anywherelse in the world, with the policy of all-encompassing multilingualism and multiscripturalism, the European Union (EU) aspires to overcome ethnolinguistic nationalists’ invariably divisive and often murderous pet insistence on the total official monolingualism and monoscripturalism (meaning, the use of a single script) in their respective nation-states. In 2019, the European Union of 28 members, employs 24 languages in official capacity, that is, all the languages, which are recognized as official in the Union’s member states. Likewise, the EU also accepts as official all these languages’ scripts (writing systems) that are three, namely, Cyrillic, the Greek alphabet and the Latin alphabet. These three scripts brush sides on the Euro banknotes, with which every European handles on an everyday basis.

Yiddish-speaking communities survive only in Israel and in some North American city quarters and towns. Under the Council of Europe’s 1992 European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, Yiddish is a protected minority language in eight European states, that is, in Bosnia, Finland, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Sweden and Ukraine. Bosnia excels in the inclusive approach to its varied ethnic and religious heritage. As the sole European state, Bosnia extends its official recognition and protection to Spanyol (Ladino), or the community language of Sephardim.[12] Not a single European country recognizes Hebrew as a minority or protected language, which is a shame to say the least. Out of the aforementioned eight states where Yiddish is protected, two remain outside of the European Union (that is, Bosnia and Ukraine). Hence, only six EU states recognize and protect Yiddish, or a mere fifth of the Union’s member states. Inexplicably and disgracefully, the main successor states of the Third Reich (as the polity that planned and carried out the Holocaust), or Austria and Germany, has no official provisions for Yiddish.

It is a moral and political scandal. What is more, this scandal is also deeply linguistic in its character, because Yiddish and German share the very same dialectal base of High German (Hochdeutsch). What bars today’s German-speakers from accessing Yiddish-language books and periodicals is the slim barrier of the Hebrew script of twenty several letters. Another obstacle is the hardly-ever openly discussed high wall of prejudice against all things Hebrew (Jewish), which is a form of latent anti-Semitism. In Greek or Bulgarian schools children learn the Latin alphabet as a matter of course, apart from their national Greek and Cyrillic letters, respectively. Hence, it is not beyond the mental capacities of German and Austrian students to master the Hebrew script.[13] In return, this skill would open to them the riches of Yiddishland’s culture in the form of thousands of books and periodicals on a myriad of subjects, which were published in growing numbers between the mid-19th and mid-20th century. Even better, this largely unknown treasure trove is almost fully digitized and available for free from the Steven Spielberg Digital Yiddish Library.[14]

Reading Yiddish-language publications for pleasure, enjoying Yiddish-language songs and films, and trying their hand at writing in this language could become yet the best available vaccination against anti-Semitism and forgetting about the Holocaust in Germany and Austria, alongside Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, and the German-speaking parts of Belgium, Italy and Switzerland. On the European scale, Brussels could facilitate this active and down-to-earth commemoration and enjoyment of Yiddishland and its culture by making Yiddish into an official EU language. Obviously, such a move should come with a long overdue recognition for this language’s Hebrew writing system as the Union’s fourth official script. Where is any difficulty present in making the EU officially known as אייראפעישער פארבאנד eyrafeisher farband in Yiddish, if it can be also referred to as the Европейски съюз Evropeiski sıiuz, Ευρωπαϊκή Ένωση Evropaïkí Énosi, or Europäische Union in Bulgarian, Greek and German, respectively?

On everyday basis not more than 17,000 people speak Irish, which became EU’s official language in 2008. As many, or even more people speak Yiddish across Europe nowadays. Yiddish is a more European language than any EU official language, which are national in their character, and as such tied to this or that member state. On the other hand, Yiddish truly belongs to all of Europe, and allows for transcending the narrow particularities of the continent’s nationalisms. What is a better lesson in practical Europeanism than embracing Yiddish?

The EU’s official adoption of Yiddish and the Hebrew script would, in no time, symbolically, visibly and in everyday practice bolster the Judeo-Christian moral foundation of the European Union. So that this foundation could truly rest on both its legs, not just one, which is the present-day norm. What could do the European states that already recognize Yiddish as a minority or regional language? First of all, at the symbolic level, these polities could (re-)introduce this language into public signage – that is, in street and place names, information plaques, and road signs – especially in these areas where Yiddishland used to extend and thrive before the Holocaust. Second, the skill of reading and writing this language’s Hebrew script should be mandatorily taught in all schools. Perhaps, outside of the German(ic)-speaking countries, the majority of students would not master Yiddish, but the skill of reading its Hebrew letters would come handy when on a visit to Israel. Third, the school subject of Yiddish language (for reading purposes) and culture should become widely available across the educational system. Fourth, the ghetto-like separation of Yiddish exiled at universities to centers or institutes of Jewish studies should stop. This language rightly belongs to university departments of Germanic languages (and perhaps, also to departments of Slavic languages). Last but not least, the states already supportive of Yiddish should lobby hard for making it into another official language of the European Union.

This is the least the EU can do for remaining true to its Judeo-Christian origins and heritage. Such a step would also ensure the active remembrance and commemoration of the Holocaust in the future generations, which is of utmost importance for bolstering secular Europe’s morality and ethics. Lest we forget. Because forgetting is to head straight for perdition.

אַזוי לאָזן ס לייענען און שרייַבן אין ייִדיש

azoy lozn s leyenen aun shraybn in eydish

(‘So let’s read and write in Yiddish’)

May 2019

[1] https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=Judeo-Christian+tradition&year_start=1800&year_end=2000&corpus=15&smoothing=0&share=&direct_url=t1%3B%2CJudeo%20-%20Christian%20tradition%3B%2Cc0

[2] https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=3_tHBAAAQBAJ&lpg=PP1&dq=roosevelt%20judeo-christian&pg=PT55#v=onepage&q=%20judeo-christian&f=false

[3] https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=Judeo-Christian+tradition%2CSoviet+values%2C+Judeo-Bolshevism&year_start=1800&year_end=2000&corpus=15&smoothing=0&share=&direct_url=t1%3B%2CJudeo%20-%20Christian%20tradition%3B%2Cc0%3B.t1%3B%2CSoviet%20values%3B%2Cc0%3B.t1%3B%2CJudeo%20-%20Bolshevism%3B%2Cc0

[4] https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=Judeo-Christian+Europe&year_start=1960&year_end=2000&corpus=15&smoothing=0&share=&direct_url=t1%3B%2CJudeo%20-%20Christian%20Europe%3B%2Cc0

[5]https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=Christian+Europe%2CJewish+Europe&year_start=1800&year_end=2000&corpus=15&smoothing=0&share=&direct_url=t1%3B%2CChristian%20Europe%3B%2Cc0%3B.t1%3B%2CJewish%20Europe%3B%2Cc0

[6]https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=Islamic+Europe%2CJewish+Europe&year_start=1900&year_end=2000&corpus=15&smoothing=3&share=&direct_url=t1%3B%2CIslamic%20Europe%3B%2Cc0%3B.t1%3B%2CJewish%20Europe%3B%2Cc0

[7]https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=%28Judeo-Christian+roots+of+Europe%29%2C%28Judeo-Christian+tradition%29&year_start=1800&year_end=2000&corpus=15&smoothing=3&share=&direct_url=t1%3B%2C%28Judeo%20-%20Christian%20roots%20of%20Europe%29%3B%2Cc0%3B.t1%3B%2C%28Judeo%20-%20Christian%20tradition%29%3B%2Cc0#t1%3B%2C(Judeo%20-%20Christian%20roots%20of%20Europe)%3B%2Cc0%3B.t1%3B%2C(Judeo%20-%20Christian%20tradition)%3B%2Cc0

[8]https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=%28Christian+roots+of+Europe%29&year_start=1800&year_end=2000&corpus=15&smoothing=3&share=&direct_url=t1%3B%2C%28Christian%20roots%20of%20Europe%29%3B%2Cc0#t1%3B%2C(Christian%20roots%20of%20Europe)%3B%2Cc0

[9] https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=%28Judeo-christliche+Wurzeln+Europas%29&year_start=1800&year_end=2000&corpus=8&smoothing=3&share=&direct_url=t1%3B%2C%28Judeo%20-%20christliche%20Wurzeln%20Europas%29%3B%2Cc0#t1%3B%2C(Judeo%20-%20christliche%20Wurzeln%20Europas)%3B%2Cc0

[10] https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=%28judeo-christliche%29%2C%28christlich-j%C3%BCdische%29&year_start=1800&year_end=2000&corpus=20&smoothing=3&share=&direct_url=t1%3B%2C%28judeo%20-%20christliche%29%3B%2Cc0%3B.t1%3B%2C%28christlich%20-%20j%C3%BCdische%29%3B%2Cc0#t1%3B%2C(judeo%20-%20christliche)%3B%2Cc0%3B.t1%3B%2C(christlich%20-%20j%C3%BCdische)%3B%2Cc0

[11] https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Żyd_z_pieniążkiem

[12] https://www.coe.int/t/dg4/education/minlang/AboutCharter/LanguagesCovered.pdf

[13] http://neweasterneurope.eu/2019/01/16/yiddish-german-from-central-europe-to-the-holocaust-and-back/

[14] https://www.yiddishbookcenter.org/collections/digital-yiddish-library